Skin color matters because we are a visual species and we respond to one another based on the way we physically present. Add to that the “like belongs with like” beliefs most people harbor, and the race-based prejudices human beings have attached to certain skin colors, and we come to present-day society, where skin color becomes a loaded signifier of identity and value. In the U.S. in particular, where we have an extremely diverse population, race still matters, but color matters, too.

In the 21st century, as America becomes less white and the multiracial community—formed by interracial unions and immigration—continues to expand, color will be even more significant than race in both public and private interactions. Why? Because a person’s skin color is an irrefutable visual fact that is impossible to hide, whereas race is a constructed, quasi-scientific classification that is often only visible on a government form.

The fact is, our limited official racial categories in the U.S.—black, white, American Indian, Asian and Native Hawaiian—are already straining under the weight of our multi-hued, ethnically diverse, phenotypically ambiguous population. (Did somebody forget about Latinos?) A conversation about “race” is no longer sufficient when our first black president has a white mother, and golfer Tiger Woods is a “Cablinasian,” and a white woman named Rachel Dolezal feels justified in claiming a black identity without having any African ancestry. The discussion has to get more nuanced and categories beyond black and white must be introduced.

In the meantime, skin color will continue to serve as the most obvious criterion in determining how a person will be evaluated and judged. In this country, because of deeply entrenched racism, we already know that dark skin is demonized and light skin wins the prize. And that occurs precisely because this country was built on principles of racism. It cannot be overstated that if racism didn’t exist, a discussion about varying skin hues would simply be a conversation about aesthetics. But that’s not the case. The privileging of light skin over dark is at the root of an ill known as colorism.

The funny thing is, the word colorism doesn’t even exist. Not officially. It autocorrects on one’s computer screen. It does not appear in the dictionary. Still, the author and activist Alice Walker is the person most often credited with first using the word colorism, out loud and in print. In an essay that appeared in her 1983 book, In Search of our Mothers’ Gardens, Walker defined colorism as “prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their color.” Light-skin preference had been common practice in the black community for generations, but Walker gave it a name and marked it as an evil that must be stopped in order for African Americans to progress as a people.

But black Americans are not the only people obsessed with how light or dark a person’s skin is. Colorism is a societal ill felt in many places all around the world, including Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, the Caribbean and Africa. Here in the U.S., because we are such a diverse population with citizens hailing from all corners of the earth, our brand of colorism is both homegrown and imported. And make no mistake, white Americans are just as “colorist” as their brown brothers and sisters.

Shankar Vedantam is the author of the book, The Hidden Brain: How Our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars and Save Our Lives. A science reporter for The Washington Post, Vedantam’s research touched on skin color and how even the most liberal-minded progressive thinkers, still display a bias towards light skin. He told the New York Times in 2010: “Dozens of research studies have shown that skin tone and other racial features play powerful roles in who gets ahead and who does not. These factors regularly determine who gets hired, who gets convicted and who gets elected.”

In the U.S., it has been repeatedly proven that skin tone plays a role in who gets ahead and who does not. Despite the fact that the word colorism doesn’t exist, researchers and scholars are now systematically tracking its existence. A 2006 University of Georgia study found that employers of any race prefer light-skinned black men to dark skinned men regardless of their qualifications. Sociologist Margaret Hunter writes in her book, Race, Gender and the Politics of Skin Tone that Mexican Americans with light skin “earn more money, complete more years of education, live in more integrated neighborhoods and have better mental health than do darker skinned …Mexican Americans.” In 2013, researchers Lance Hannon, Robert DeFina and Sarah Bruch found that black female students with dark skin were three times more likely to be suspended at school than their light-skinned African-American counterparts.

Suffice it to say, one’s health, wealth and opportunity for success in this country will be impacted by the color of one’s skin, sometimes irrespective of one’s racial background. Even darker-hued white people have different experiences than their lighter-hued Caucasian counterparts when it comes to access and resources. Colorism is so deeply ingrained in the fabric of this nation that we are all implicated and infected by its presence. And the sad thing is, for many people the lessons of color bias begin in the home.

In black families, Latino families, Asian-American families and obviously interracial ones, too, skin colors can vary in microscopic gradients or in obvious shades of difference. Luckily many parents are able to create a safe-space in the home where skin color differences only matter when it is time to buy sunscreen for the beach. But too often, the pervasiveness of a color hierarchy in the outside world seeps into the household and becomes part of the implicit and explicit teachings of parenting.

That is not to say that the solution to solving our color problem as a country lies in the home, but that is precisely where the conversation should begin. From day one, parents of every color should begin to celebrate color differences in the human spectrum instead of praising one over the other or even worse, pretending we’re all the same. Then, we could have a more public facing, cross-cultural dialogue about the more global problem of colorism and plot its necessary demise.

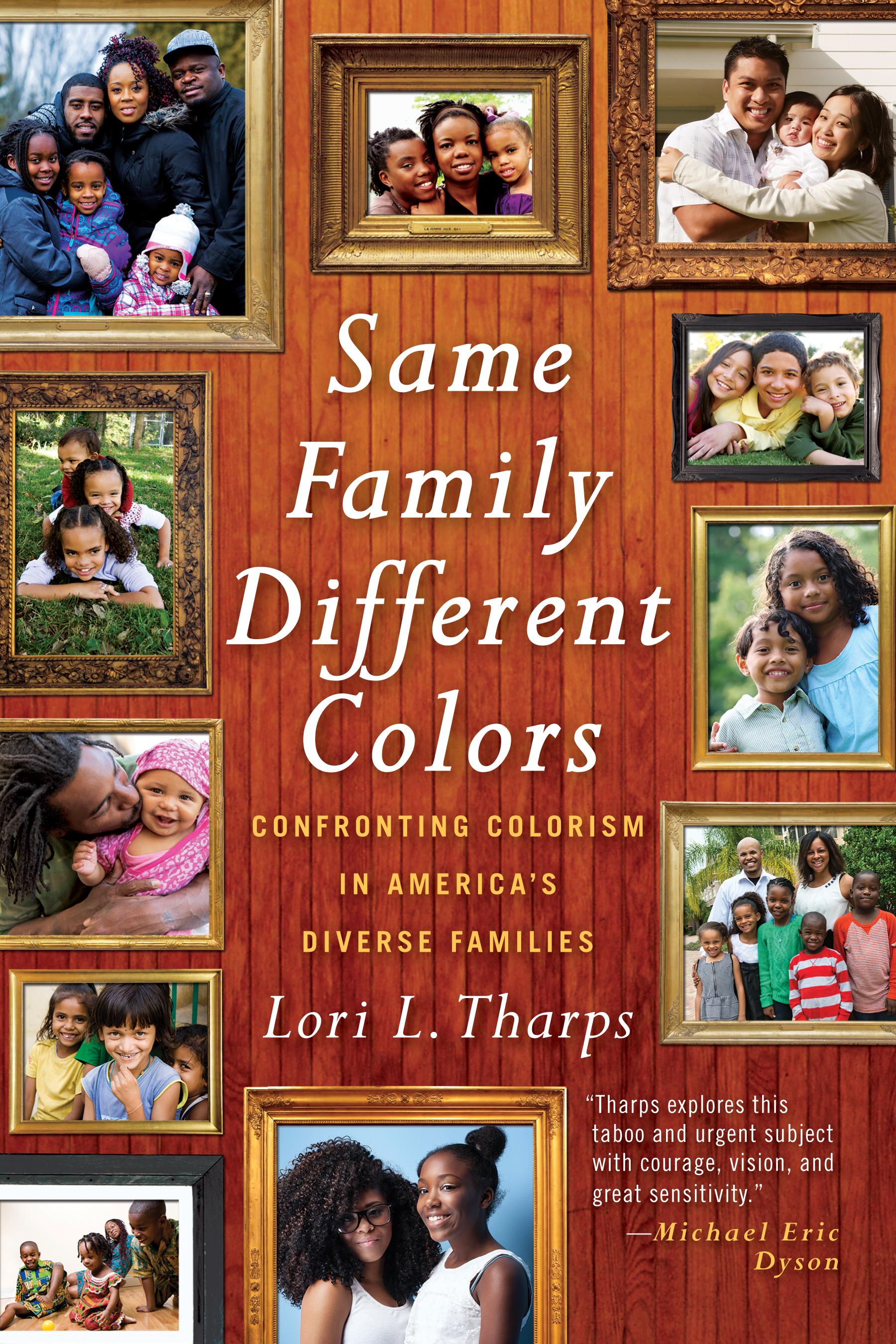

Adapted from Same Family, Different Colors: Confronting Colorism in America’s Diverse Families by Lori L. Tharps (Beacon Press, 2016). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com