Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time . com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

In 1951, the idea was newsworthy: “Unlike other mortals,” opened a TIME article that year, “the 42,000 members of the Diners’ Club need never pay the waiter when they wind up a spirited evening on the town. They simply sign the check, get billed once a month.”

In the 65 years since, such a magical experience has become normal: Today, about 70% of Americans have a credit card. So how did credit cards become so ubiquitous?

An early clue comes from 1888, when Edward Bellamy wrote Looking Backward, 2000-1887, a novel about a time traveler exploring a utopian future, and imagined using a “credit card.” (It was a utopian future, so fairness ruled the day and “credit corresponding to his share of the annual product of the nation is given to every citizen on the public books at the beginning of each year.”) Bellamy’s idea, however, worked to a large extent like a debit card does today—not like what we know today as a credit card.

But the concept of consumer credit is even older than that. “It’s characteristic of agrarian societies,” says Lewis Mandell, financial economist and author of The Credit Card Industry: A History. “They very often have to finance agricultural operations by borrowing money for seed and other things to keep them going until harvest.”

Later, patrons at upscale stores who didn’t want to carry cash would have their purchases recorded in a ledger book at some stores, but that became problematic as urbanization and larger stores meant that recognizing customers and trusting them to pay wasn’t quite as a reliable method as it used to be. So, stores would provide a means of identification with the name of the store, and perhaps a number to confirm you were who you said you were. These credit indicators were only good at one store, but they were really the beginning of consumer credit in the way we think of it today.

Still, the technological transformation from ledger book to plastic cards took a while.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The idea continued to expand in the early 20th century. For example, Western Union introduced “metal money” in 1914, a metal plate given to select customers allowing them to defer payment, and a decade later General Petroleum Corporation issued similar metal cards for gas and repair services at their gas stations. These companies took the idea of a single-store credit token and brought it to businesses that had multiple branches.

The Charga-plate came a few years later, embossed to allow a sales clerk to quickly record an imprint of the information on the card (a technique, Mandell notes, that is still an option today, if not in widespread use), and was popular with department stores, which would issue their own Charga-plates. And in 1946, John C. Biggins, of Flatbush National Bank of Brooklyn, NY, created a system called “Charg-It,” a bank-issued card that let people in a two-square-block radius charge purchases to the bank. The area was limited by necessity—merchants had to leave sales slips with the bank—but promised ease for locals who could use the card at multiple businesses.

Then came the Diners’ Club card, in 1950, providing proof of credit that could be honored at any participating store.

Founded by Frank X. McNamara and Ralph Schneider, Diners’ Club was the first independent card company. (They were soon joined by Alfred Bloomingdale, who had had a similar idea.) Where many other early credit cards failed within a few years, Diners Club was successful. Starting with 200 card holders and at 14 restaurants in NYC, the cards “ushered in the era of the credit card” says Mandell. In its first year the “Club” expanded to 42,000 card holders and handled more than $500,000 of transactions at 330 establishments in a single month—five years in, there were 300,000 members.

There were limits on this universality; like credit card companies do today, it relied on agreements with merchants to honor the card and pay the fee associated (then about 7%). Initially it was more of a “charge card,” requiring users to pay in full monthly, rather than allowing them to carry the revolving balance that is now typical of a “credit card.”

Some pinpoint Franklin National Bank’s 1952 card as the first true “credit card” which you could use to buy now and pay later, with interest.

As TIME put it in 1958: “Credit, which was once the sign that a person had trouble meeting his bills, has taken on a glamorous new meaning in recent years. Now a man with a credit card can rent a plane or boat or car, live it up in nightclubs, take a safari to Africa and even get a Kelly Girl for temporary office help. Why? Because of the Credit Card Game.”

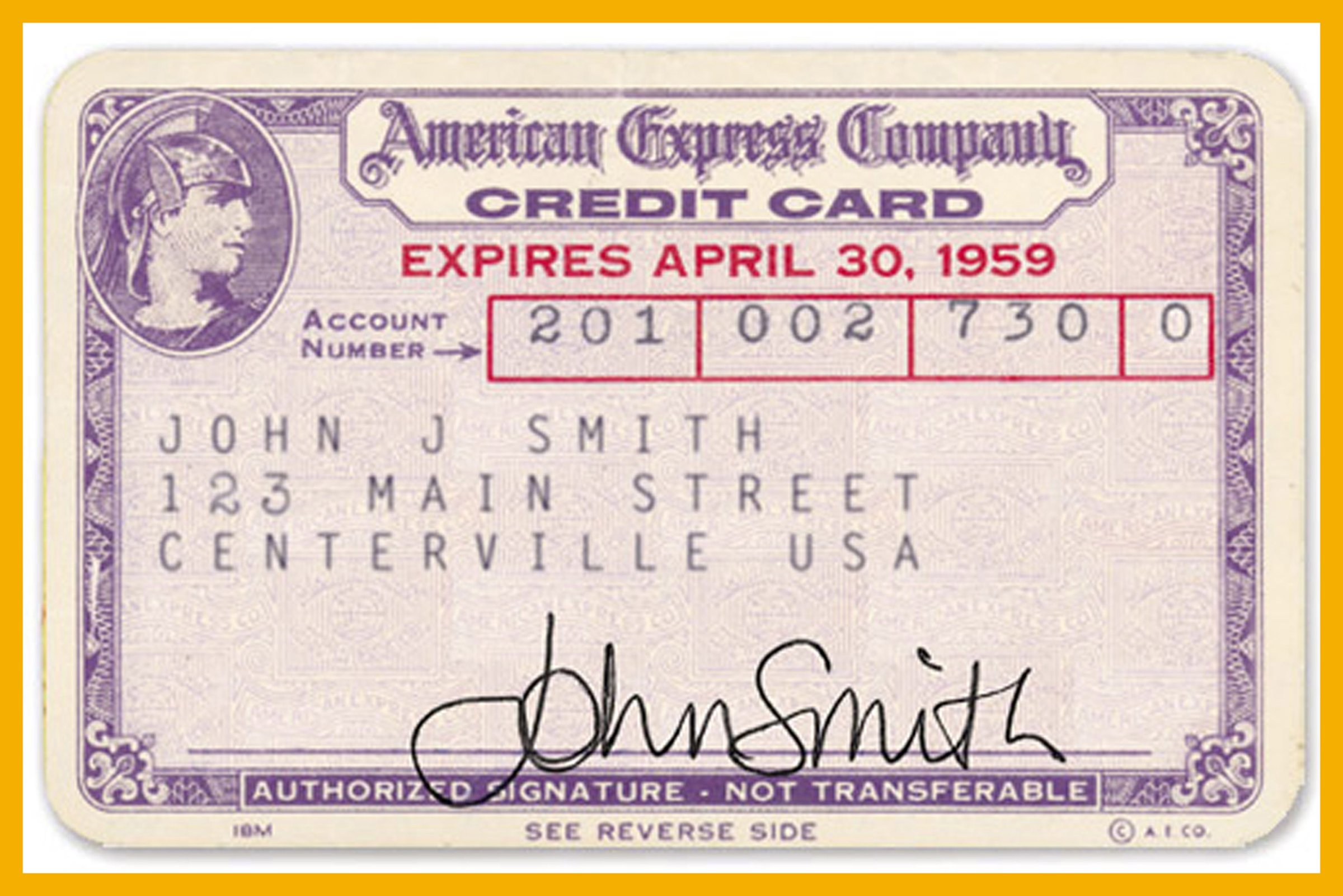

Once the idea was out there, the competition began. American Express, long known as a purveyor of traveler’s checks, started their own credit-card program in 1958, and the Hilton hotel chain’s Carte Blanche expanded their affinity card into a credit card. That same year, Bank of America (later Visa) tested out the “Fresno Drop” in Fresno, Calif, mailing 60,000 BankAmericards to residents in the area. Though not everything went well—fraud was an issue—the experiment in universal, revolving credit was enough of a success for the bank to decide to expand the card, which would later become Visa.

As credit card companies grew, so did the number of merchants who accepted their cards. Personal credit’s traditional geographic borders no longer applied.

In 1959 American Express introduced a plastic charge card, and Diners Club made the switch in 1961. And that magnetic stripe on your card has its own history: It was developed by IBM in the 1960s, and the story goes that the designers were stumped as to how to get the bit of magnetic tape attached to the card until an engineer’s wife suggested ironing it on, which worked. Today, many card companies are replacing those stripes with chip technology—which, despite some complaints about slowness, is still faster than the original way of doing things, when you might have had to wait while a sales clerk made a phone call to confirm you were approved to make a purchase with a credit card.

And now, mobile payment systems like Apple Pay might seem to be encroaching on even that newer technology—and even Mandell isn’t sure that the plastic credit card is still here to stay.

“Most people feel that credit cards may not have much of a future,” he says, “but people have been saying that now for over 50 years.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com