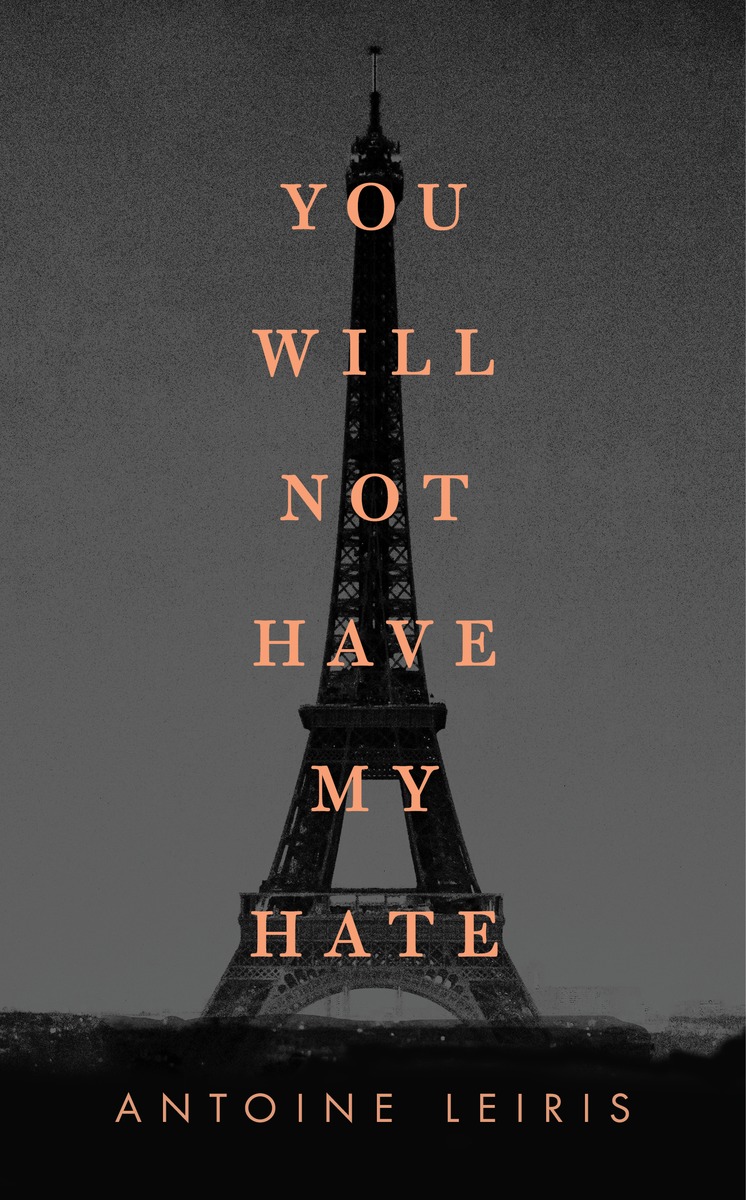

After his wife, Hélène, was killed in the Paris terrorist attacks of November 2015, Antoine Leiris found himself suddenly having to care for his 17-month old son alone. In his new memoir, You Will Not Have My Hate, based on a viral Facebook post he wrote after the attacks, he grapples with what his life will be like now that he must fill the roles of both parents, and yet somehow live for himself.

Nov. 22, 2015, 9 a.m.

I have just dropped Melvil at daycare. He didn’t cry. I move slightly to the side so he won’t see me watching him, behind one of those windowpanes in the center’s glass facade. It is like a big bowl where we can see the fish swimming around. Sometimes we tap on the glass to get them to notice us. He is already playing with his musical book. It is a journey, in the space of a few pages, around the world of instruments. The bandoneon played by a llama, the balalaika by a bear. A fox in a Venetian gondola plays the mandolin.

At the daycare center, everyone knows. When I arrive each morning, every person I see wears a mask. The carnival of the dead. Even if I tell them the fable of a man who will not lose control, I cannot persuade them to take off the masks. I know that, for them, I am no longer me: I am a ghost, the ghost of Hélène.

Melvil is alive. Almost as soon as he gets there, the masks come off. He enters on tiptoe, says good-bye to me, smiles, and one burst of laughter is all it takes for the funeral faces to fall to the bottom of the toy chest.

It is time for me to go home.

I pick up the mail before walking upstairs. The mailbox is barely even open before a flock of envelopes escapes from it, paper in different shapes and sizes scattering on the floor around me. There are thick envelopes, containing very long letters, a whole life shared with me. There are kraft envelopes, filled with children’s drawings for Melvil. There are simple postcards. For a moment, at least, words have replaced the little box’s usual stack of bills.

I open the first envelope. Read the postcard inside it as I climb the stairs. Kind words sent from the United States. At the door of the apartment, I pick up a note left by a neighbor: “If you need me to help with your son, don’t hesitate to ask. Your neighbor across the hall.”

I put the letters on the living room table. The color of one of the envelopes catches my eye. An old-fashioned off-white. A missive from another age. The paper has a letterhead. The man’s name is Philippe. I imagine a gray-haired gentleman sitting at his writing desk. I slip inside his words. He is reacting to the message I posted on Facebook. His letter is beautiful. I feel snug, curled up in this envelope, where the sun shines. Then, at the bottom of the page, like a signature, these words: “You are the one who was hurt, and yet it is you who gives us courage.”

Watching from a distance, you always have the impression that the person who survives a disaster is a hero. I know I am not. I was struck by the hand of fate, that’s all. It did not ask me what I thought first. It didn’t try to find out if I was ready. It came to take Hélène, and it forced me to wake up without her. Since then, I have been lost: I don’t know where I’m going, I don’t know how to get there. You can’t really count on me. I think about Philippe, the author of this letter. I think about all the others who have written to me. I want to tell them that I feel dwarfed by my own words. Even if I try to convince myself that they are mine, I don’t know if I will live up to them. From one day to the next, I might drown.

And suddenly, I am afraid. Afraid that I won’t be able to meet people’s expectations. Will I no longer have the right to lack courage? The right to feel angry. The right to be overwhelmed. The right to be tired. The right to drink too much and start smoking again. The right to see another woman, or not to see other women. The right not to love again, ever. Not to rebuild my life and not to want a new life. The right not to feel like playing, going to the park, telling a story. The right to make mistakes. The right to make bad decisions. The right to not have time. The right not to be present. The right not to be funny. The right to be cynical. The right to have bad days. The right to wake up late. The right to be late picking Melvil up from the daycare center. The right to mess up the “homemade” meals I try to make. The right not to be in a good mood. The right not to reveal everything. The right not to talk about it anymore. The right to be ordinary. The right to be afraid. The right not to know. The right not to want. The right not to be capable.

From YOU WILL NOT HAVE MY HATE by Antoine Leiris, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Librarie Arthème Fayard and translation copyright © 2016 by Sam Taylor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com