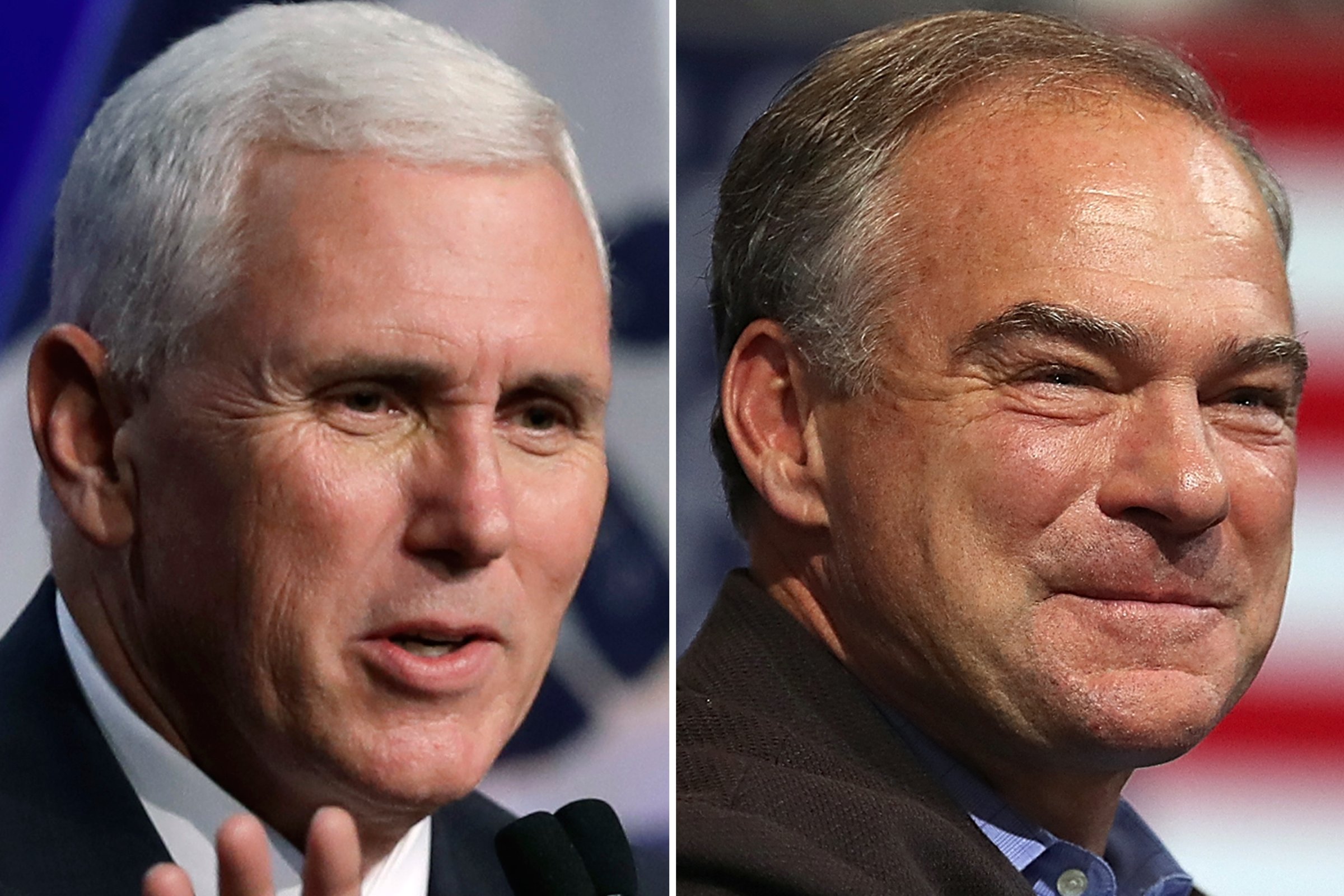

The Vice Presidential Debate on Tuesday at Longwood University is poised to be a welcome moment of civility and substance. Historically, the vice presidential debates have been serious and memorable, and this year’s nominees, Gov. Mike Pence and Sen. Tim Kaine, are principled and articulate. During an election campaign focused far more on the contrast of personalities than the issues, the country may likely find this debate a high point.

The idea that 90 minutes of reasoned dialogue will seem so exceptional demonstrates that something serious ails our democratic life. American politics will never know an age of dispassionate reason (in the founding era, it gives perspective to note our first Treasury secretary was killed in a duel by a former vice president). But today’s predicament feels genuinely perilous. We are losing our capacity to engage in civil discussion, to reckon with complex problems and to empathize with fellow citizens across the political divide.

How might we right the ship? Many believe the answer lies in changes to the mechanics of our democracy—non-partisan redistricting, changing the presidential primary system, campaign finance reform. But there are no policy panaceas. The solution to what ails us must lie in something deeper: preparing citizens in their formative years for the concrete, practical and noble if often messy work of democratic life.

Preparing students for the duties and rights of citizenship was once the animating purpose of education in America. Yet for two generations now education has increasingly disregarded teaching about the workings of government, in favor of a narrower focus on skills training and career preparation.

Civics education was once a mainstay of the K-12 curriculum. In higher education, the “liberal arts” core once focused on giving citizens coming of age the knowledge to participate in public affairs. But “liberal arts” has since drifted far from its true meaning and become equated with learning unaffiliated with a particular career track. In fact, the Latin root of “liberal” is the same as for “liberty.” “Citizenship studies” perhaps conveys the original sense of the ancient phrase.

Against this backdrop, it is fitting that Tuesday’s debate will take place at a historic university with a mission to prepare graduates for precisely this kind of work. It is especially fitting that it will take place at a public university committed to such work.

With the opportunity of hosting the debate, Longwood is offering a wide array of courses this semester, across virtually every academic department, focused on issues in the election. These are a precursor to a bold new core curriculum that will make citizen leadership its north star across disciplines, while using courses in a given major to provide graduates the tools they need for particular career tracks.

The collective challenges of our 21st-century democracy don’t fit neatly into categories, so we will teach our students to think about them across disciplines, to assess evidence and assemble civil arguments, and to exercise the practical skills of working with one another to make progress in solving them.

Residential college campuses like Longwood are not the only setting for acquiring such skills. But such places can powerfully reinforce the citizenship preparation of a liberal arts curriculum. In student government and in campus newspapers, students learn to exercise their democratic muscles in relative safety. And for all the criticism (not always unjustified) they receive for their lack of diversity in various dimensions, where else these days besides college campuses do Americans of genuinely different backgrounds and beliefs live and learn side by side, forced to confront one another and challenging ideas face-to-face in a seminar, dorm room or dining hall?

The Commission on Presidential Debates believes deeply in the benefits of holding the four general election debates each presidential election cycle on college campuses so that students can see the energy and interplay of ideas that drive democracy.

It’s also a reminder that each new generation must learn the habits of democracy anew. As we confront fundamental discord in our democracy—manifest in the current campaign, culminating over recent decades—we should recall the crucial connection between education and citizenship, so much lost for two generations. Educational reform to give focus to teaching students the essential elements of how to participate in our civic life together is not a quick fix, but it should hold appeal across the partisan spectrum.

America will endure the rancor of the 2016 election. But we should not be mystified as to how we got here or risk being complacent about the future.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com