This post is in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A version of the article below was originally published on the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

Responding to news of the singer’s passing in January 2016, the official NASA twitter account tweeted “Rest in peace, David Bowie. ‘And the stars look very different today.’” For Bowie, one of humankind’s hitherto unanswered questions was—to quote from his most famous song—“(Is there) Life on Mars?” In this vein he followed in the footsteps of H. G. Wells, another popular culture icon who was among the select few featured on the cover of The Beatles’ “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967).

Both Bowie and Wells grew up in a London suburb, Bromley. Wells was also born there. Both could not wait to escape from suburbia. Both used talent and imagination through art as part of the process of leaving behind their past. Thus, when writing about Bowie, Simon O’Hagan argued that this “explains how, in so many of his songs, the reality of his suburban upbringing co-exists with themes of outer space.” For O’Hagan, “Bowie was in some ways the H. G. Wells of the jukebox.” Renowned for his bestselling science fiction stories and their audio-visual adaptations such as by Orson Welles and Steven Spielberg, Wells not only wrote serious newspaper articles about life on Mars but also incorporated Martians into his fiction juxtaposing fantasy scenarios with suburban realities.

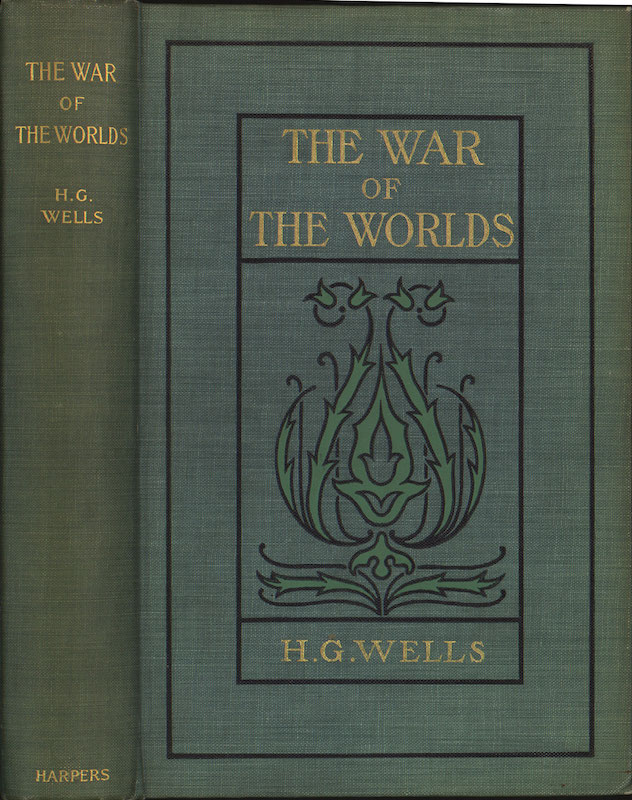

Since landing on Mars in August 2012, NASA’s robot rover has been exploring the Red Planet to try to help answer the question posed by Bowie and Wells, among others. Unsurprisingly, NASA’s Mars Curiosity Project has attracted extensive world-wide media coverage, particularly given the manner in which myriad works of science fiction have both reflected and encouraged our fascination with Mars, Martians, and all that. At present the jury is still out concerning life on Mars, but this has not prevented continuing speculation that, given our present-day surveillance society, we have been, and still are being, watched from Mars. In The War of the Worlds (1898), Wells introduced the idea that, like bacteria under a microscope, people on Planet Earth were being studied by Martians by way of preparation for the first interplanetary war. He made plausible—or at least not out-of-this-world—the possibility of extra-terrestrials acting as spies, invaders, and empire-builders.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The War of the Worlds’ prescience and afterlife

As a result Wells, like Bowie, occupies a prominent place in our present-day thinking about Mars, as evidenced by his prominent role in, say, NASA’s online “Mars chronology” or the press kit prepared for the launch of the Mars Rover in 2011. Today, Wells’s ghost still looms large over popular attitudes and contemporary media debates about the Red Planet. In part, this reflects the enduring fame of The War of the Worlds as—to quote Robert Crossley—“a central text in the cultural history of Mars.”

Written during the late nineteenth century and set during the early twentieth century, The War of the Worlds continues to attract readers and resonate with audiences during the 21st century. For most readers, the story is just an excellent read, an exciting sci-fi page-turner. But its enduring appeal derives also from a timeless focus upon the impact of invasion and war upon present-day society through a storyline touching upon such perennial themes as complacency about homeland security, the need to take account of the unexpected, the ferocity of aggressive imperialism, the devastation and mass panic prompted by sudden invasions, and the impact of science and technology upon warfare and weaponry.

The War of the Worlds remains in print, still sells well, and has been translated into numerous languages. Moreover, the book has enjoyed an extremely successful multimedia afterlife. Thus, Wells’s pioneering story has been taken, and continues to be taken, to new audiences across the world through adaptations, most notably on film by George Pal (1953) as well as by Steven Spielberg and Tom Cruise (2005), on radio by Orson Welles (1938), and through music and stage rock operas by Jeff Wayne (1978 et seq.). The story’s subject matter, most notably its massive potential for vivid imagery, has made The War of the Worlds a focus also for bubblegum and cigarette cards, comics, computer games, e-books, graphic novels, mobile phone apps, and podcasts, among other outputs.

Wells as “the Shakespeare of science fiction”

For most people, and particularly the media, the big literary event in 2016 is the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. But this year also marks two Wellsian anniversaries, that is the 150th anniversary of Wells’s birth and the 70th anniversary of his death. Hitherto these Wellsian anniversaries have attracted far less media and popular attention, even if they are—to quote Durham University’s Professor Simon James—“every bit as important as that of Shakespeare. His novels The Time Machine, The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds were the first true science fiction novels in the English language.” Indeed, Brian Aldiss, the science fiction grand-master, has represented Wells as “the Shakespeare of science fiction,” the author largely responsible for inspiring and popularizing science fiction, particularly the alien invasion and time travel sub-genres. For many commentators, Wells is viewed as a prime source of inspiration for Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek films and television series, while BBC television’s time travelling Doctor Who proves a straight steal based upon the Time Traveller in The Time Machine.

Read more at the Harry Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass Blog

Peter J. Beck, Emeritus Professor of History at Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, UK, is the author of The War of the Worlds: from H. G. Wells to Orson Welles, Jeff Wayne, Steven Spielberg and beyond, which was published by Bloomsbury Academic in August 2016. His other books include Presenting History: Past and Present (2012), Using History, making British Policy: the Treasury and the Foreign Office, 1950-76 (2006), and Scoring for Britain: International Football and International Politics, 1900-1939 (1999).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com