Last year, the world shuddered at the lifeless image of Aylan Kurdi, the Syrian toddler whose body washed up on a Turkish beach. This summer, we cheered the Olympic refugee team that captured our hearts in Rio. These refugee stories exemplify the type that make headlines and trend in our Facebook feeds. They come at either the harrowing beginning—or the triumphant end—of the refugee journey.

But what about the years in between?

Conflicts are lasting much longer now. So the median “living in limbo” time—when refugees in a protracted crisis are unable to return to their homes or establish new ones—has skyrocketed from nine years in 1993 to an astonishing 26 years now. That’s an entire generation.

These years in limbo, mostly unseen and unrecognized by the world, can be grinding and desperate. People displaced by war and the environment have increased from 42 million to close to 65 million in the past eight years. The humanitarian system is simply not currently equipped to transition these refugees from their former lives to a sustainable and worthy future.

Haifa, 40, a Syrian refugee I met last year in a hardscrabble neighborhood in Jordan, typifies the life of purgatory that millions face. To feed her family, the mother of four sends two of her sons to work instead of school because she says: “We have no other choice.”Before they fled their home, she said: “they never missed a day of school.” As we spoke, her husband simply stared off in silence. Years of fleeing bombing inside Syria, combined with restrictions against him working in Jordan, have sapped him of words and of hope, she said.

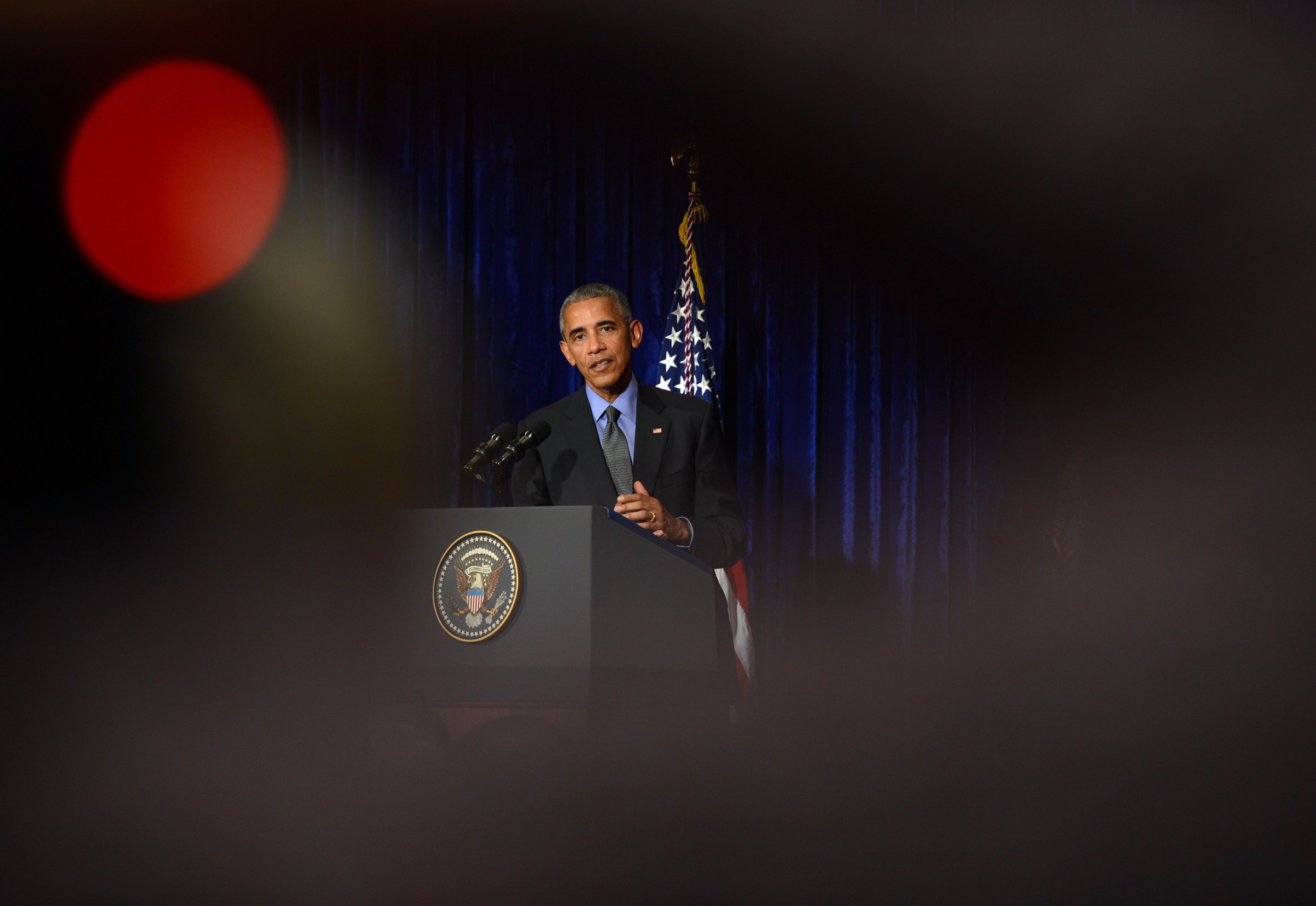

President Obama has called for a special Leaders’ Summit on Refugees at the U.N. General Assembly this month, essentially his last, best chance to influence the world’s response to refugees. Here are three things he must get world leaders to do in the name of Haifa, her family and other refugees living in limbo:

1. Ensure the legal status of refugees.

The uncertain legal status of refugees in many contexts poses major challenges for people fleeing crises, who often lose their official documents along the way. For example, an estimated 200,000 refugees lack a valid Ministry of Interior card in Jordan, while an estimated 70% of Syrian refugees and almost all Palestinian Refugees from Syria in Lebanon lack a valid residency permit. This impedes refugees’ access to services and livelihoods and condemns them to live in constant fear of detention or deportation. The U.S. should use all possible leverage with host countries to clarify the legal status of refugees, dismantle policy obstacles and fill funding gaps, so refugees can thrive as respected members of their new societies who can “stand on their own two feet”—a phrase I hear invoked repeatedly by refugees I meet.

2. Lift up refugee women and girls.

Emergencies often offer a unique opportunity to transform gender dynamics as women and girls lead their families through tough times. CARE, the humanitarian organization I lead, heard this loud and clear when asking several current and former refugee girls for their “messages of hope” to President Obama in advance of his refugee summit. “Refugees have talents and skills that should not be abandoned but instead must be improved and invested in,” said Sajeda, 16, a Syrian refugee living in Jordan. Sajeda, who lives with her mother and her four siblings, wants to be a journalist so she can use her voice to create change for her people. But she wonders whether that is a pipe dream in Jordan given how difficult it is for Syrians to get a job there. The U.S. government has to do more to ensure that girls such as Sajeda don’t just languish in limbo. They can lead themselves and their families out of limbo and into self-sufficient futures. The U.S. should advocate for an advisory council of women refugees who could present needs and proposed solutions to U.S. government officials on a routine basis. This council could be modeled after the U.S. Advisory Council of Human Trafficking Survivors.

Read more: Is Germany Failing Female Refugees?

3. Prioritize funding that benefits both refugees and the host population.

Developing countries host 86% of the world’s refugees. Refugees are also increasingly living in urban settings, not in traditional refugee camps, changing how refugee and local populations interact. With crises dragging on, these host countries are struggling to support both their own people and refugees, leading to increased social tension. Imagine, for instance, if the entire population of Canada moved into the U.S.—this is the equivalent of what Jordan is facing right now with Syrian refugees. We need a “one neighborhood approach” to ensure that host communities’ needs are addressed alongside those of refugees. In Jordan, for example, CARE has a vocational training and job placement program in partnership with the private sector that benefits both Syrian refugees and Jordanians in need living in the same community.

If President Obama wants to leave a stronger legacy of helping refugees—the largest population the world has ever known—he needs to galvanize world leaders to nurture the hopes of those stuck between the home they once had and the one they dream of having.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com