On the morning of September 11, 2001, photographer Lyle Owerko remembers being jetlagged and unable to sleep in his Tribeca apartment when he heard a sound that defied description. That sound was the impact of an American Airlines jet hitting the World Trade Center’s north tower. Conjuring a scene from the film King Kong where the monster is terrorizing New York, Owerko recalls, “It sounded like a gorilla threw a city bus at a building. There is no way I can describe what it sounded like.”

Owerko’s camera bag with all of his gear was still packed and ready to go beside his door as he ran out of his apartment to investigate. On the way out, his building’s superintendent told him that he saw a plane hit the tower. He ran down Broadway and then crossed over on Chambers Street and immediately started taking photos.

“Things were still normal at the moment,” he says. “I remember people chuckling at me and saying ‘where’s the fire buddy?’ as I ran with two cameras and a bag strapped around me.”

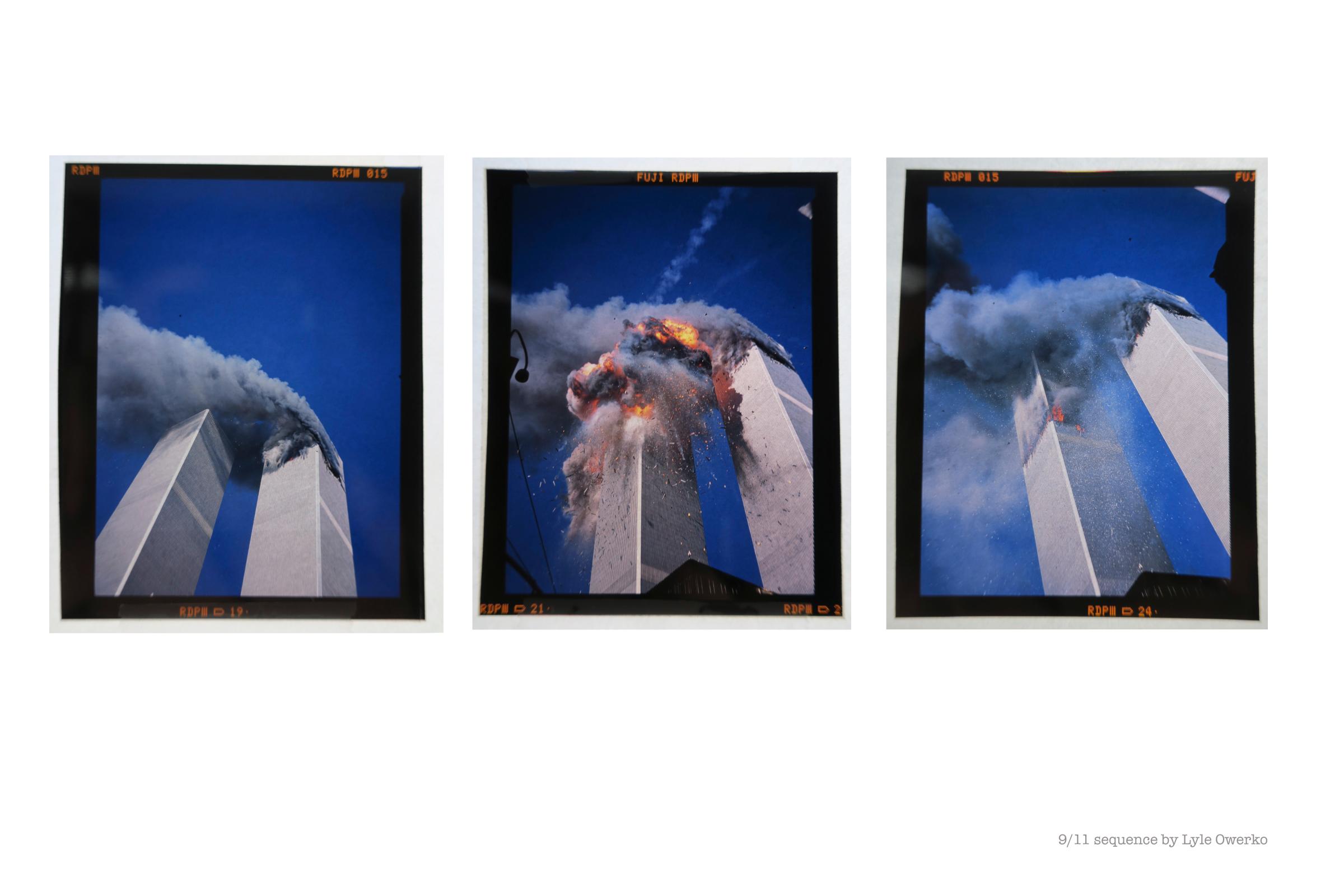

In a time right before most photographers switched to digital cameras, Owerko was equipped with a 35mm and a medium format Fuji 645zi film cameras. “There was kind of a beauty to working back then,” he says. “You were preconceiving your shots. And being judicious about what you shot and even being conservative.” Owerko quickly strategized his photos and carefully moved around the streets to find the best perspective. “There was a lull for a few minutes,” he remembers. “The reason I went to Vesey and Church streets was that it put the sun at my back and I was able to compose a story of the two towers – one that was obfuscated and one with no marring on it and at that point I thought: ‘There’s your cover.’ The one tower that’s smoking and the one that’s stoic and defiant.”

At that moment, people started screaming. “Someone said there’s people jumping and that’s when the temperature really changed and the crowd began reacting in horror,” Owerko remembers. “Because [I had been to] Tanzania I had a 400mm lens in my bag and I switched my 35 and I started photographing these people in the last moments of their lives.”

Unknowingly the second plane began to approach the towers. “I heard the sound of this jet,” he says, “and I thought it was air traffic being redirected. I saw it off in the distance. The plane did this little shoulder shrug where it dipped its wing and when I saw it arc, then I knew its intention. It was a very predatory move and having just spent a month in Africa it was like watching a cheetah going into stalk mode.”

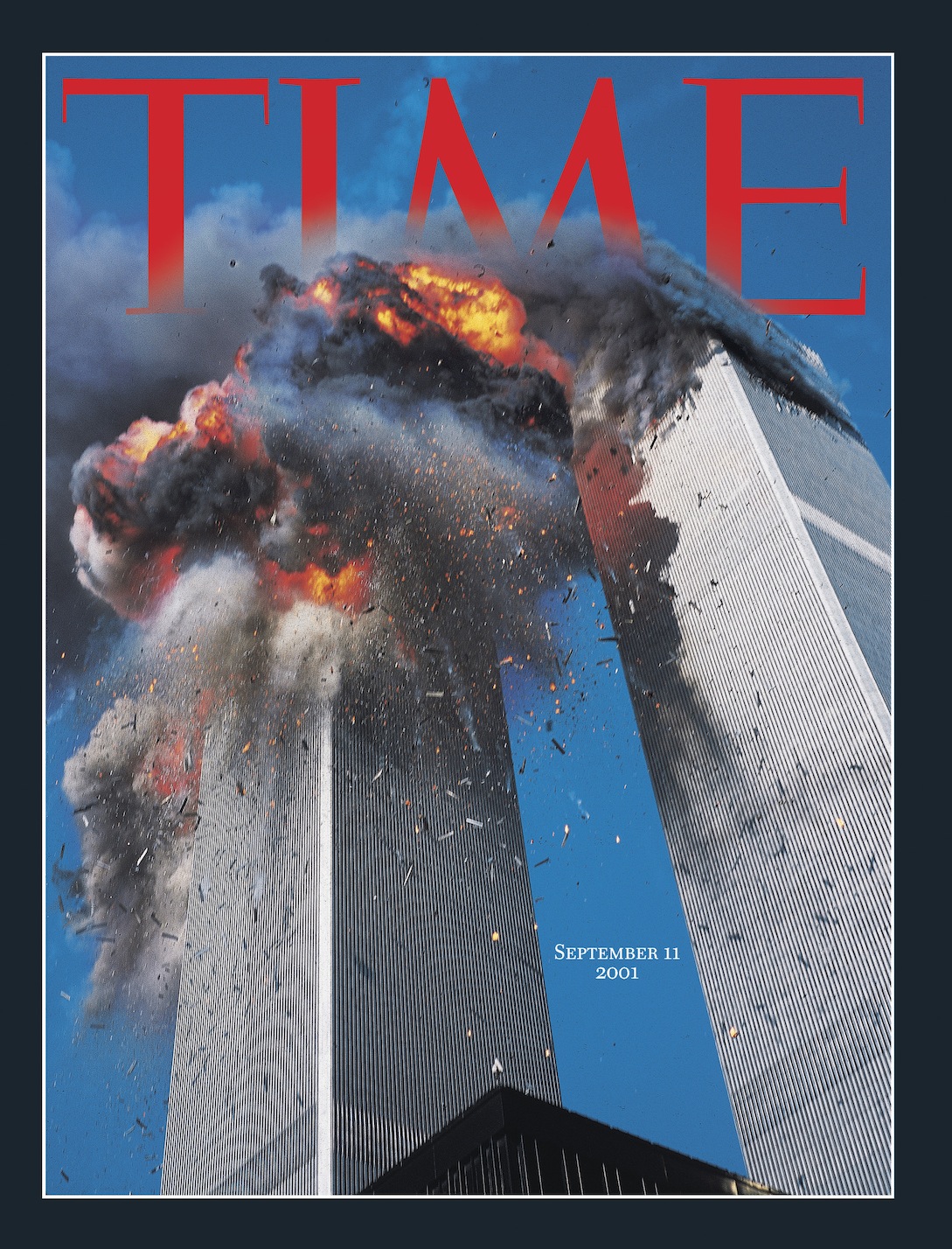

In that horrific moment, Owerko shot two frames with his Fuji 645zi medium format camera in hand. “I waited until it hit,” he says, “and when it hit I had no idea, but I thought something would occur. And when it hit, again it made this incredible beyond movie theatre sound. And then nothing happened for a second until this fireball of heat and debris erupted out of the backside of the building and that’s when I caught the cover shot.”

A split second later, he was composing the second shot. “And then the debris started raining down on us,” he says. “I put my hands over my head as airplane parts and building parts started scattering around the police officers, the bystanders, and me. There were screams and an eruption of people’s voices in shock.”

Now, Owerko can still conjure up that moment. “It’s like every synapse in my body was firing,” he says. “It was all beyond belief. It was like standing in the middle of a three dimensional Hollywood film.”

Convinced that he had the shot, Owerko started walking up Broadway toward a nearby lab. “That’s when the first building fell,” he says. “I started seeing these gusts of debris coming through the side canyons and I started taking shots of people running up Broadway.”

Once the lab processed his images, Owerko remembers the owner telling him: “You have the cover of TIME magazine.” And he did.

By early afternoon, his pictures were on the desk of the director of photography at TIME, MaryAnne Golon. “The minute I saw it,” Golon recalls, “I walked to Jim Kelly’s office with it and said ‘here’s our cover’.”

Two days later, Owerko went to his local newsstand. “When I first saw it on the cover I wasn’t sure if it was mine,” he says. “It was so surreal because it was a weirdly intimate photo of my own experience, and I opened the cover and checked the byline and it was my image.”

Today, Owerko feels the photo is not his anymore. “It’s the world’s photo,” he says. “It belongs to history.”

Lyle Owerko is a photojournalist and commercial photographer based in San Francisco. You can see more of his images from 9/11 in the book The Day That No Bird Sang.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com