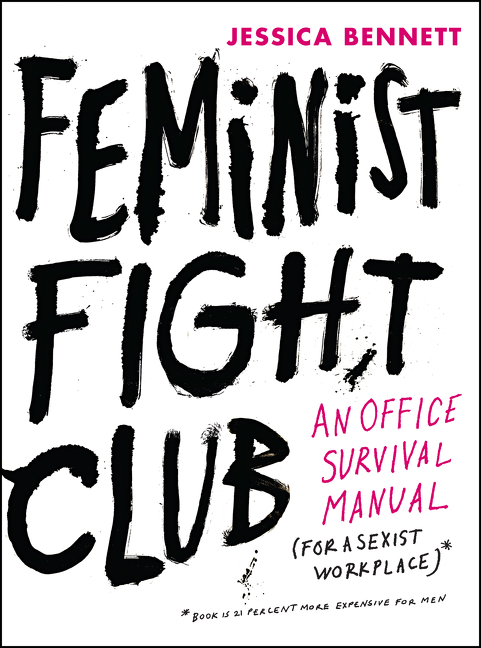

Jessica Bennett is a contributing editor at The New York Times and the author of Feminist Fight Club: An Office Survivial Manual for a Sexist Workplace

Dissecting the way women speak has seemingly become a favorite pastime of late—our pitch, our sorrys, even our punctuation. This has been especially clear this election, with increased scrutiny placed on Hillary Clinton, who has been called “shrill”—a word used twice as frequently to refer to men than women—faced “manterruptions” (sigh, Matt Lauer) and had plenty of others attempt to impose meaning on what she says.

This, of course, is old news for Hillary; she’s endured it all. Remember back 2008, when a John McCain supporter asked of the candidate, “How do we beat the bitch?” (McCain laughed, quipping awkwardly that it was an “excellent question.”) Hillary could brush it off, and perhaps so could we, except that research has shown that even subtly sexist words—not just “bitch,” but say, “shrill”—influence voters’ likelihood of supporting a candidate, and whether they support female politicians at all.

When it comes to women and their own speech – their vocal fry, the apologies before speaking, the way we tend to use uptalk to end our statements in a question? – there’s an important caveat to all that advice we receive about not doing it: what’s been deemed the ideal way to speak doesn’t necessarily match the way women actually talk. Linguists will tell you clearly: male and female speech patterns have always differed. Women tend to have more versatile intonation patterns; they place more emphasis on certain words; they speak about more personal topics. And while the masculine style of communication at work is to give orders—as in, “Here’s what we need to do” or “We have to do better”—the feminine style is to persuade. “I have an idea that I want you to consider.” Or she may phrase her idea as a question: “What do you think of this approach?”

It has long been a truism that women lead popular linguistic trends: creating new words, playing around with sounds, creating verbal shortcuts that catch on in the vernacular (pretty sure it wasn’t a man who first LOLed). Yet it is the masculine style of speech–succinct, straightforward, confident—that is associated with workplace leadership and power. Which means that when it comes to work, women are often left to adapt their language to speak more like men: female speech is perceived as insecure, less competent, and sometimes even less trustworthy. No wonder Margaret Thatcher hired a vocal coach to help her sound less “shrill.”

But wait, there’s more. Yes, women can adapt, but they mustn’t adapt too much – lest they sound masculine. In her book, Talking from 9 to 5, linguist Deborah Tannen describes a woman who received negative feedback when she tried to talk like her male peers—but was able to remedy the situation by adding words like “sorry” back into her speech. As Tannen noted later: How could anybody possibly not lack confidence if she’s constantly being told she’s doing everything wrong?

At the end of the day, there is no right way to talk—especially if you want to sound like yourself. But here are some common trip wires you may want to approach with caution.

1. The Over-Apologizer

Once upon a time, the word “sorry” was reserved for things a person might actually be sorry for: spilling wine on the new white silk you’d borrowed without asking; denting your mother’s car; screwing something up–like really screwing something up—at work. These days it’s more like a crutch: a space filler, a hedge, a way to interject, state an opinion, to politely ask without offending, to state an opinion, say “excuse me,” or just about anything that involves speaking up or stating an opinion at all.

There are plenty of times when saying “sorry” actually works. But if your audience is not a prickly individual but a full conference room or a reply-all email list, know this: You may say, “Sorry to interrupt, but I think . . . ,” but what you sound like is, “I have zero confidence in my idea–why should you?”

Threat Level

LOW: When You’re Actually Sorry

Allow for a moment a refresher on the fundamentals of a well-deployed “sorry.” A textbook apology comes when a speaker realizes she has done something harmful or offensive to the addressee and wants to put their relationship back on an even keel. Apology accepted? Great! The relationship can once again flourish, no (further) harm done.

MEDIUM: The “Excuse Me” Sorry

In today’s off-label use, “I’m sorry” and “excuse me” are attention getters immediately preceding a request or demand; delicate throat clearings to mitigate an unpleasant situation or confrontational request (for instance, “I’m sorry, I think you may be sitting in my seat,” meaning a demand: “Yeah, I’m gonna need you to get out of my seat”); and as a euphemistic disguise for anger and frustration, when we expect something to have been done and it hasn’t (at least not to our standards).

MEDIUM: The Polite Sorry

Yep, sometimes “I’m sorry” is simply a “linguistic tip of the hat,” as Tannen calls it, one of many social niceties that help conversation flow. When you want someone to clarify what she said: “I’m sorry, I’m not sure what you mean.” When you are interrupting others to ask a question: “Oh I’m sorry, I’m looking for so-and-so, have you seen him?” British natives—men as well as women—use “sorry” in this way all the time, Tannen notes, yet no one thinks it reveals insecurity or dooms them to a bleak future.

2. Upspeak

When upspeak doesn’t involve turning a statement into a question (“Yes, I’m sure?”), it involves adding a question to the end of a statement (“You know what I mean?” “Does that make sense?”). Both women and men do it (George W. Bush was known for it), but women do it more often than men; white women do it the most; and–in one study, of Jeopardy contestants–researchers found that the more successful a female contestant became the more she did it, while the opposite was true for men.

Threat Level

USEFUL: To Stop a Manterrupter

There’s at least one bit of research that finds some may use uptalk as a defense mechanism to prevent others from cutting you off. (Remember, women are twice as likely to be interrupted.) Turns out that questioning tone in your voice might actually be good for something: it indicates you’re not yet finished.

LOW: To Check In

As if to say, “Are you still with me? Are you paying attention here?”

MEDIUM: To Elicit Affirmation

Affirmation is nice, and sometimes a questioning tone will elicit words of encouragement: “Totally!” “Yes, I agree.” But if your intent is to actually impress your listener, it seems ma-a-a-a-aybe a teensy bit unwise to present your statement in a way where you possibly sorta undermine yourself . . . ahem. You know what I mean?

HIGH: To Convey Confidence

In Talking from 9 to 5, Deborah Tannen describes a male CEO who explains that he often has to make decisions “in five minutes” about projects on which his staff may have worked five months. He uses this rule: if the person making the proposal seems confident, he approves it. Ending your statements in a question or, for that matter, beginning them with an apology? The opposite of confident.

3. Hedging

They’re called “hedges” come in many forms. There’s the trembling qualifier (“I’m not sure if this is right, but . . .”), serving to counteract the fear that a statement might actually be wrong. There are filler words like “kind of,” “sort of,” “apparently,” “supposedly,” and so on, adverbs with just the tiniest hint of an opinion. They are permission words: used to lessen the impact of an utterance or qualify a statement to make you sound equivocal. While kin to “sorry,” this category is different—in that it’s not a direct apology so much as apologetic air-stirring, a shy knock on a door, or as former Google exec Ellen Petry Leanse de- scribed it, a way to “put the conversation partner into the ‘parent’ position, granting them more authority and control.”

She is right: technically our statements would sound more assertive if we removed both the “but” and the qualifier preceding it. BUT! Perhaps this is the very reason why we use qualifiers to begin with: to sound less assertive, softer, less pushy, less demanding. To create the effect of a thought we both, speaker and listener, have arrived at together.

Threat Level:

USEFUL: For Emphasis

“That meeting was just terrible.” “That meal was just wonderful.” Those “justs” aren’t uncertain, they’re emphatic.

LOW: To Make a Request

“What if we maybe stop by for a minute?” “Could I possibly ask you a couple of questions?”

MEDIUM: To Buy Time

A well-deployed “um” or “you know” can give you a moment for your brain to collect your thoughts–—another version of the time-tested “That’s a good question, Bob,” which manages to somehow balance condescension and compliment in one.

HIGH: The Confident Swagger Hedge

Used in office scenarios to actually make up for the fact that you don’t have an answer, while still managing to give an opinion. “Well, I don’t know who has the time to know everything about [insert topic at hand]–—but it’s my feeling that we should [insert opinion anyway].” If you can employ it, use it. Men do it all the time.

HIGH: The Aggressive “Actually”

It’s the “talk to the hand” of the adverb world, as the journalist Jen Doll put it: a sneaky word, used to say “you’re right, I’m right” but without actually owning the correction. Consider: “Hi, Jennifer.” “Actually, it’s Jessica.” Or “The team is all here.” “Actually, we’re waiting for Ashley.” “Actually” can lessen the blow, but it can also be used to deliver a powerful bomb. “The numbers are down sixteen percent.” “No, ACTUALLY, they’re up by five.” Just don’t let it sound like you’re surprised by your own conviction.

Most of us don’t think much about the subtleties of language. It flows out of our mouths, sometimes we regret it, most of the time we move on. But when it comes to women,how we talk matters more than we might think.

Excerpted from Feminist Fight Club, copyright © 2016 by Jessica Bennett. First hardcover edition published September 13, 2016, by Harper Wave, an imprint of Harper Collins Publisher. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com