Those who thought that the publication of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in July 2007 marked the end of the franchise couldn’t have been more wrong.

As well as the succeeding movies, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them due for release this November and the highly-acclaimed Cursed Child play delighting audiences in London, J.K. Rowling has kept diehard Potter fans satisfied with regular essays and explanations from the wizarding world on the interactive fansite, Pottermore.

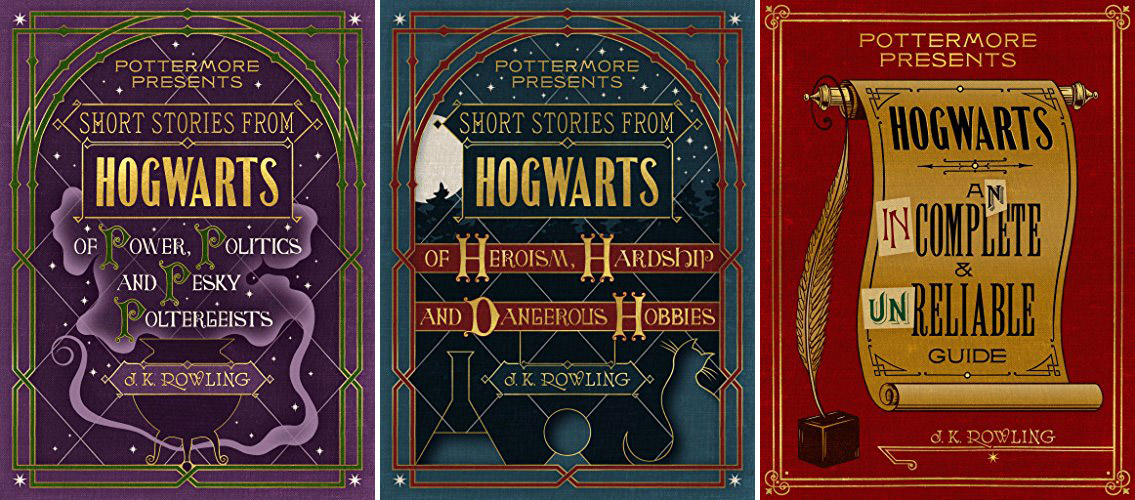

Now her enlightening updates and personal reflections have been knitted into three short story collections, released as $2.70 eBooks Tuesday. Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide, Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists and Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies are packed full of surprises and intricate details about much-loved characters, insight into magical history and revelations of Rowling’s writing regrets. Here are seven things we learned:

1. Why the Hogwarts Express was controversial to begin with

The Hogwarts Express is an integral part of Harry Potter. It’s on the magic train that Harry, Ron and Hermione first meet, where Harry first comes across a Dementor (which causes him to pass out) and the last, moving scene in the final book revolves around the Platform 9¾ drop off.

But getting the Hogwarts Express ready to transport witches and wizards to school was no easy feat – secret records at the Ministry of Magic detail a “mass operation involving one hundred and sixty-seven Memory Charms and the largest ever mass Concealment Charm performed in Britain”. The next morning, Muggle railway workers in Crewe woke with the uncomfortable notion they had mislaid something important – while villagers in Hogsmeade were were amazed to see a “gleaming scarlet steam engine” waiting in a station they didn’t know existed.

Even though the mass operation went to plan, many pure-blood families were outraged by the idea of their children using “unsafe, insanitary and demeaning” Muggle transport. However, their objections were overruled by the Ministry who said if their children wanted to go to Hogwarts, they had to get the train.

2. What came before the Sorting Hat

Before Rowling decided on a Sorting Hat as the way of dividing the students into the four houses, she dabbled with the idea of four statues taking charge. Writing in Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide, Rowling explains that after deciding against a “Heath Robinson-ish machine that did all kinds of magical things before reaching a decision,” she “placed four statues of the four founders in the Entrance Hall, which came alive and selected students from the throng in front of them while the school watched”.

This didn’t feel right though, and she eventually settled on the Sorting Hat – inspired by the classic notion of pulling names out of a hat to choose someone for a game.

3. Which of J.K. Rowling’s creations made life most complicated

The Marauder’s Map—a magical document that allowed Harry to see all the goings on at Hogwarts—became “something of a bane to its true originator (me) because it allowed Harry a little too much freedom of information,” Rowling writes. However, despite the complication of the plot device, Rowling “on balance” is glad she did not let Harry leave the map in Mad-Eye Moody’s office as she “like[s] the moment when Harry watches Ginny’s dot moving around the school in Deathly Hallows“.

Like the Marauder’s Map, Hermione’s Time-Turner, which enabled her to time travel, opened up “a vast number of problems” for Rowling. To solve it, she emphasised, by way of Dumbledore and Hermione, how dangerous it would be to be seen in the past.

She also had Hermione give the Time-Turner back when she was done using it and smashed all the remaining devices in during the Department of Mysteries battle. “This is just one example of the ways in which, when writing fantasy novels, one must be careful what one invents,” Rowling writes. However the Time-Turner makes a comeback as the central plot device in the Cursed Child play.

4. What happens to Professor Quirrell in Sorcerer’s Stone

Professor Quirrell is “turned into a temporary Horcrux by Voldermort” in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Rowling writes in Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists. This explains his weakened state; “he is greatly depleted by the physical strain of fighting the far stronger, evil soul inside him”.

5. What Azkaban’s name means

In Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists, Rowling writes that the name of the wizard’s prison, Azkaban, derives from Alcatraz – the high-security prison located in the San Francisco Bay, which Rowling describes as Azkaban’s “closest Muggle equivalent, being set on an island”.

The rest of the word is inspired by the Hebrew term “Abaddon,” meaning “‘place of destruction’ or ‘depths of hell'”.

6. Who Minerva McGonagall’s parents were

Undoubtedly a favourite of the Hogwarts teachers, Transfiguration professor and later headmistress Minerva McGonagall is the first child of a Scottish Presbyterian minister named Reverend Robert McGonagall and a Hogwarts-educated witch named Isobel Ross.

Reverend Robert, a Muggle, believed that Isobel attended a selective ladies’ boarding school in England and even after their child was born, Isobel did not reveal her true identity. Writing in Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies, Rowling explains that eventually Isobel confessed the truth to Robert, who was “profoundly shocked by her revelation, and by the fact that she had kept such a secret from him for so long”.

7. What Remus Lupin’s werewolf condition really meant

One of the most interesting revelations Rowling has made about the books since the series ended was the fact that Remus Lupin – one of her “favourite characters” – and his condition of lycanthropy (being a werewolf) was a “metaphor for those illnesses that carry a stigma like HIV and AIDS”.

“The wizarding community is as prone to hysteria and prejudice as the Muggle one, and the character of Lupin gave me a chance to examine those attitudes,” she writes.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Kate Samuelson at kate.samuelson@time.com