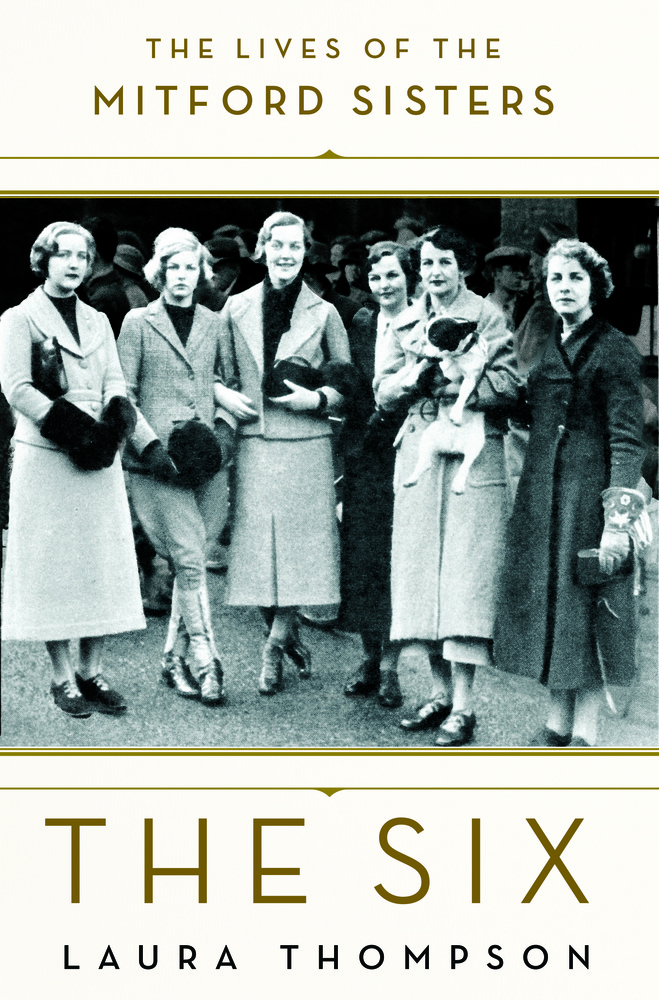

“Take six girls, all of them rampant individualists, and let them loose upon one of the most politically explosive periods in history. That is the story of the Mitfords.”

So begins Laura Thompson’s biography of some of the most infamous sisters of the 20th century. The oldest daughter, Nancy Mitford, became a celebrated author (The Pursuit of Love, Love in a Cold Climate) with a reputation for snobbery. Diana Mitford married Oswald Mosley, founder of the British Union of Fascists, and both were imprisoned during WWII, thanks in part to Nancy’s informing on them. Unity Valkyrie Mitford was a fascist, too—in fact, she became a close personal friend of Adolf Hitler. When England and Germany went to war, she attempted suicide. Jessica Mitford was on the opposite end of the political spectrum: a communist, she sided with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War and was an advocate for American civil rights when she moved to the States. She, too, earned literary fame for her memoir Hons and Rebels. While she never forgave Diana for her fascism, she did sympathize with Unity, despite her relationship with Hitler. Deborah became a Duchess through her marriage to Lord Andrew Cavendish, and Pamela—perhaps the most “normal” of the bunch—was a countrywoman. (They also had a brother, Tom, who died in World War II.)

All of which prompts a question: How did one family produced such a remarkable range of sisters?

The new book The Six: The Lives of the Mitford Sisters explores the answer to that question. “The way in which they were written about in the ’30s and what have you, it is almost like the Kardashians,” Thompson says, though she’s quick to clarify that most of them had extremely serious intellectual accomplishments to their names. “You would never get girls brought up that way, and six of them all sparking off each other, and then launch them into a world where those things happened in that space of time—it couldn’t happen again.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Their upper-class childhood was a combination of “formality and anarchy,” Thompson says. They were largely autodidacts, combing through the family library to study what interested them, and they each had a level of confidence that “would be very hard to achieve today, because nothing bothered them. When Diana said ‘Being hated means nothing to me,’ I think she meant that … They just were themselves and they thought that was great.”

That unique brand of confidence is part of what makes the Mitford sisters fascinating to some young women today—even in spite of their often unforgivable political and personal cruelty. They could be unfeeling and backstabbing toward each other, and more heinously, Unity was a self-proclaimed “Jew hater” and Diana said she doubted the Holocaust really killed six million Jews. Still, the more liberal Mitfords, Nancy (a sort-of socialist) and Jessica, inspire modern admiration—in fact, J.K. Rowling named her daughter after Jessica.

Each of the Mitfords was known for charm, “which can be a lethal quality,” says Thompson, who met and was herself charmed by Deborah and Diana before their deaths. “It can have a coldness to it, but also makes life rather feel better when you’re bathing in the glow of it.” (You might wonder why someone like Unity would want to charm someone like Hitler—but she did.)

Even among those who find all of the Mitfords abhorrent, there’s a level of fascination with them as “prize exhibits in a museum of Englishness,” Thompson writes in the book. The appeal seems to stem in part from their own love-hate relationship with their social status. They had an “ability to mock their own myth as well as this marvelous egalitarian straightforwardness, almost like talking to very clever children,” she says.

“Of course the English are so ambivalent about class,” says Thompson. “They’re all glued to Downton Abbey as I believe you [Americans] were, but at the same time pretending, ‘Oh God, we really shouldn’t be, isn’t it frightful, but we are.’ And the Mitfords fall into that uneasy sort of, God they’re fascinating—we shouldn’t really be [fascinated], but what the hell type of thing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com