In the 1970s Staten Island was undergoing major infrastructure changes and a huge population expansion. It was ten years after the opening of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, which connected the island to Brooklyn in 1964 and, for the first time, to the rest of the city by land.

It also had a reputation for being provincial compared to the rest of the city and still does today. In the early eighties, photographer Christine Osinski was looking for a new home with her husband after high rents forced them out of their Soho apartment in Manhattan. A therapist she was seeing at the time recommended that Osinski look for a cheaper place on Staten Island. “We used to take the ferry in the summer to cool off but never got off the ferry,” she says. “Once we got off initially it felt like a time warp and it was hard to believe it was part of New York City. It seemed remote and had its own unique character—clearly a working class sensibility.” It was a place Osinski could relate to coming from the South Side of Chicago. She grew up in a house she describes as, “similar to the one Michelle Obama says she’s from. It was a brick bungalow in a harsh muscular area with lots of factories.”

The move to Staten Island came a few years after studying for her Master’s at Yale in 1974. During that time, she recalls the all-male faculty in the photo department was initially dismissive of her photographs of people and often saw them as funny. “Once I got to Yale I began to recognize where I was from,” Osinski says. “There was a contrast between me and my working class roots compared to the backgrounds of the other students.”

Osinski says her professors and fellow students thought her pictures were interesting but found the people comical. “Their response to my photos made me begin to question where I was from,” she says. “I began to question why I was photographing what came naturally to me, specifically the middle class. I also began to wonder if I was making fun of them. So I stopped photographing people.”

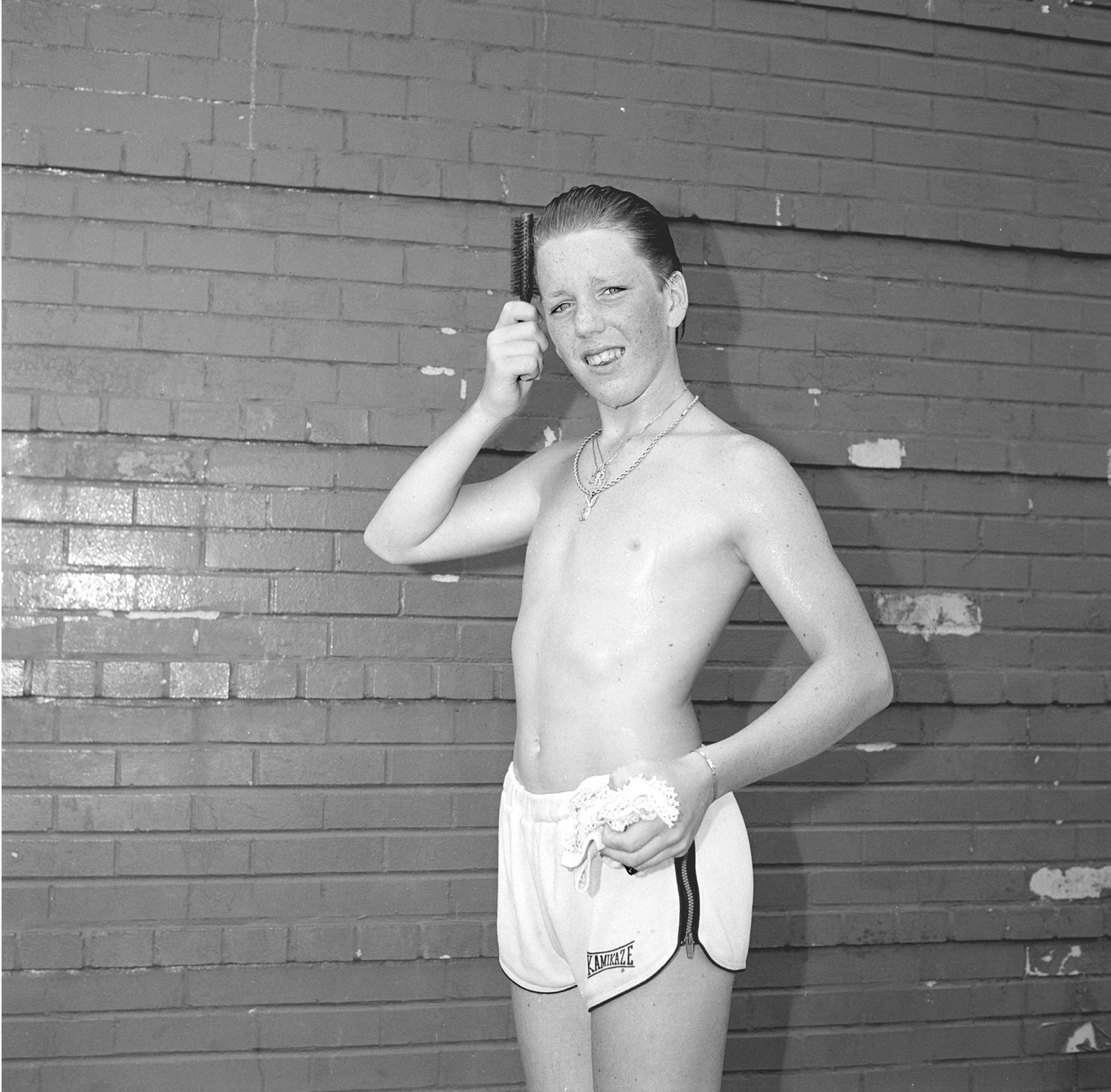

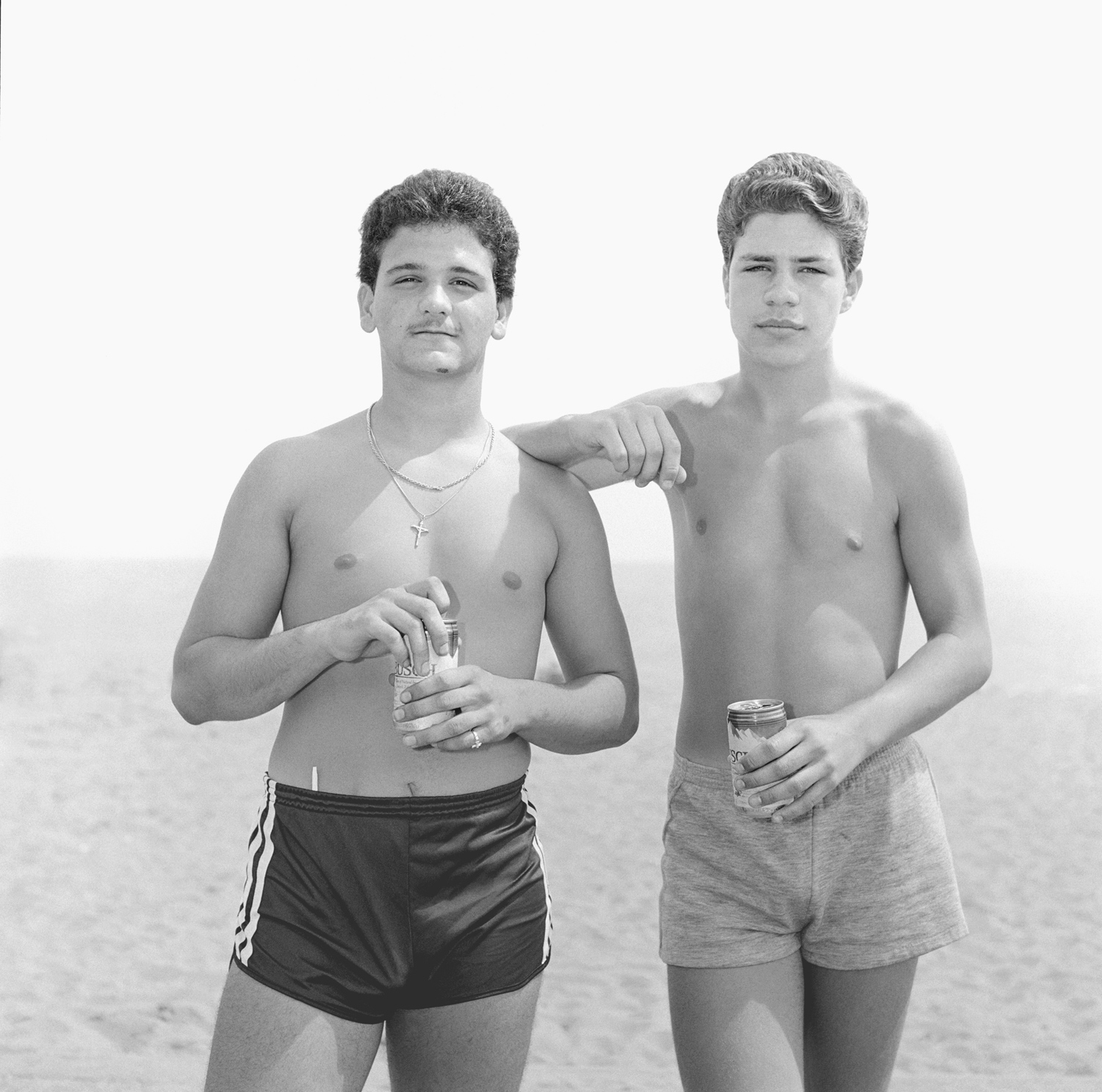

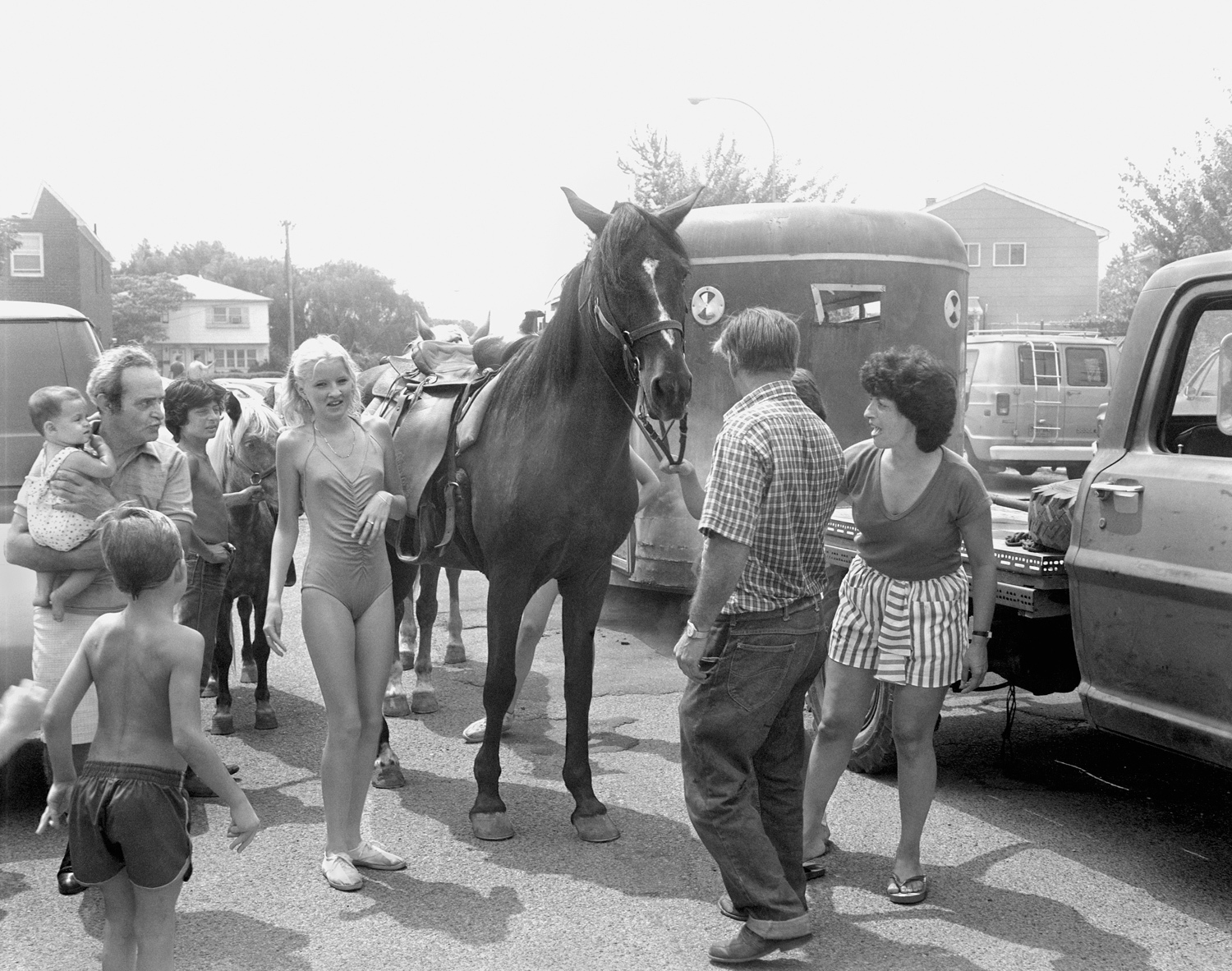

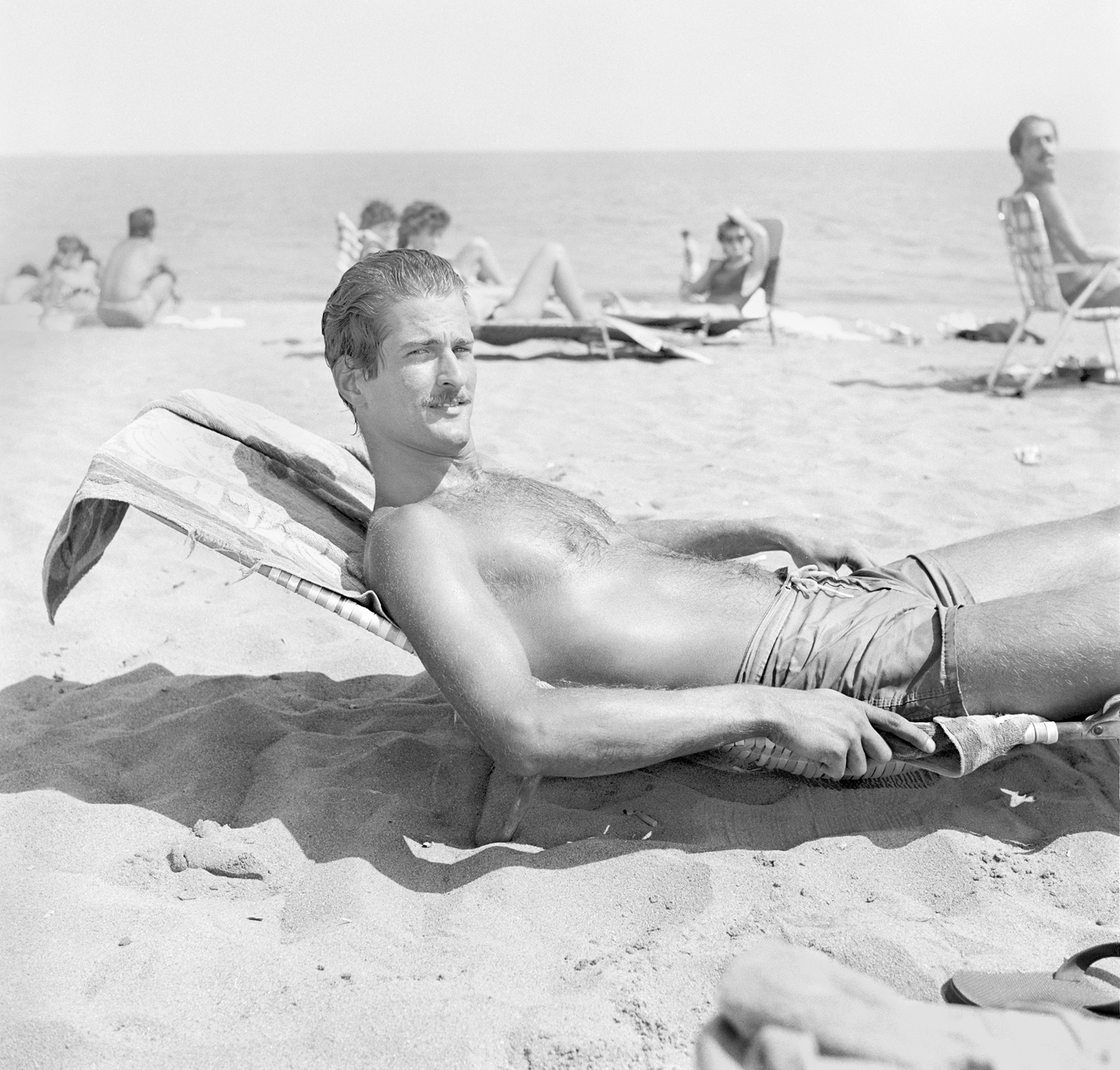

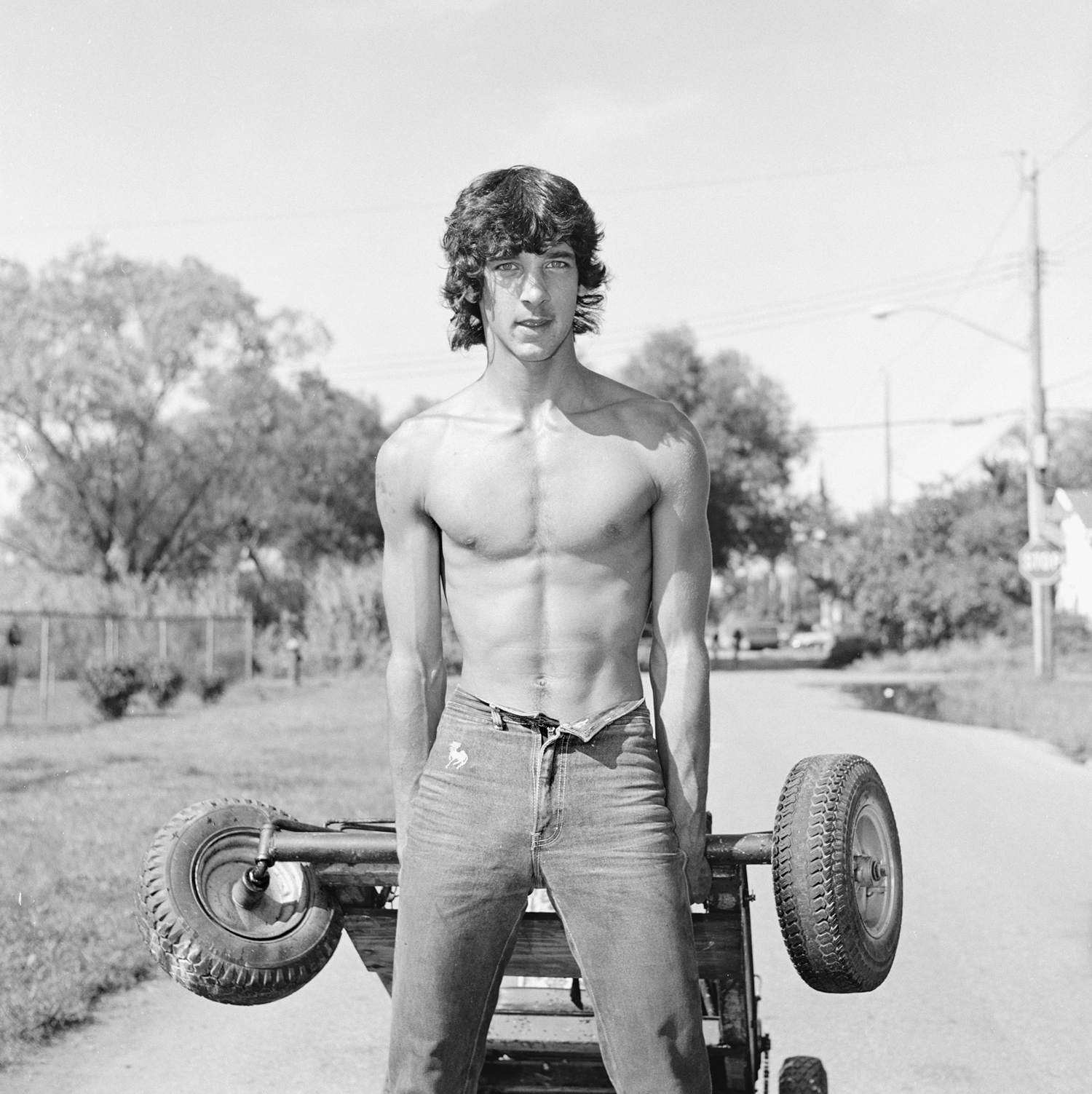

Years later, she began photographing Staten Island to explore the place where she was now living. “The Island was a goldmine for pictures. Everything seemed interesting,” Osinski says. “Mostly I went out walking for long periods of time. When I began photographing the people were very small in the landscape, but eventually I moved closer and they became the primary focus of my photographs. There were a lot of people outside, people having block parties, at parades and kids hanging out. People were very curious and having the 4×5 camera on a tripod helped me. It was just nice being outside and meeting people. You just never knew what was going to happen. It was an adventure.”

Osinski says she felt Staten Island was undergoing a big shift and that the new construction always seemed so sad to her. “In the photo of ‘Forest View Estates’, there’s not a tree in sight,” she explains. “The materials were cheaper than the older houses and it seemed like a symbol of what people were opting out for. It seemed like it was in keeping with a certain working class idea of what success is. The ‘new’ is what many people seem to strive for because it seems better.”

In her images, Osinski shows duplexes that aspire to be mansions. “Some of it seems funny, like the man building the Grecian columns on the house. It’s like misplaced grandeur,” she says. She depicts cramped new housing developments and homes separated by brick walls decorated ostentatiously with Putti giving a nod to the Old World and a taste of the Island’s many Italian immigrants. “The photo of the animals shows the clash of the old and new living side by side until the old finally gives way to the new.”

After spending 1983 and 1984 obsessively working on the project, she realized that it was almost impossible to make prints. The work was made with an uncoated Linhoff lens on a 4×5 camera, making all of the highlights totally blown out and almost impossible to print properly. Today Osinski is a professor of art at Copper Union where she’s worked for 28 years. But during a residency at Light Works in Syracuse she began scanning some of the negatives and realized with the new digital scanning capability she could finally achieve the quality she had always hoped to have with the work.

“I generally look to photograph the supporting players and not the main characters,” she says. “I tend to look at the minor players and the overlooked places. A lot of my work is about the familiar so that it begins to take on a more unusual presence. It makes you question your assumptions about things you know. Right under your nose there might be something that you’re not familiar with. Maybe taking pictures is an opportunity to make someone look again.”

Now with the unpublished archive finally scanned and in order she hopes to create a new book and is looking for support on Kickstarter.

You can see more of Christine Osinski’s work here.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy photo editor of TIME. You can follow him at Twitter at @paulmoakley.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com