As the fall campaign began, it felt like the presidential election was already over. Following the Republican national convention, a televised disaster, party elders had hoped their nominee would make a concerted effort to broaden his appeal. But the candidate had instead devoted himself to picking fights and nursing grudges. There was a growing debate about whether he was actually sane.

The Democrats had begun the summer worrying about their candidate, a Washington workhorse of 30 years who lacked the star power of the man they’d nominated four years before. They’d fretted over their own convention, that protesting activists would undo the fragile peace between the party’s liberal and moderate wings.

But the DNC had been all professionalism and patriotism, at least compared with the Republicans’ horror show. At kitchen tables, Americans were talking about the frighteningly real prospect the Republican candidate could start a nuclear war. As Labor Day approached, the question wasn’t whether the Democrats would win the White House, but how big their win would be.

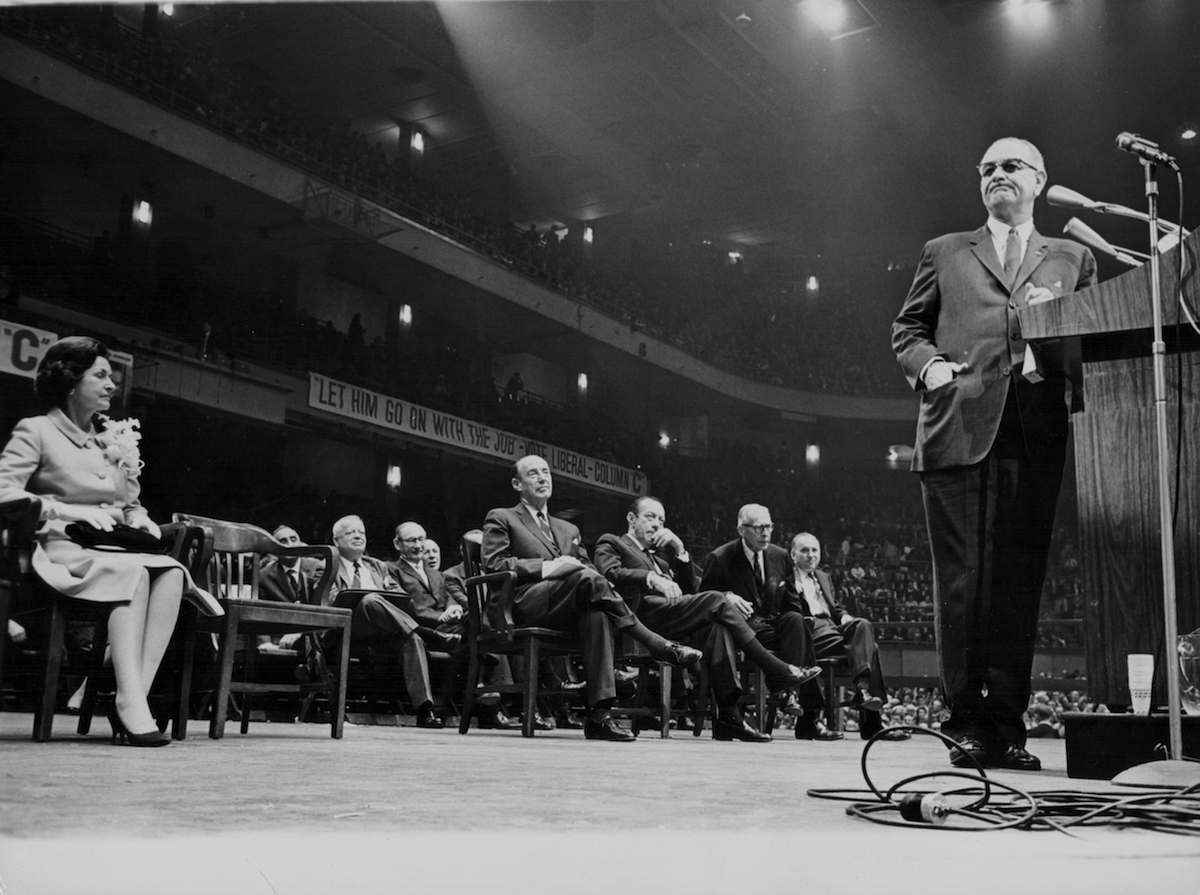

Bigger, it turned out, than any presidential victory before or since. The year was 1964, when Lyndon Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater, winning a larger percentage of the popular vote than any president in history.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

By now, it’s clear that Hillary Clinton’s campaign sees some similarities between 1964 and today. The campaign remade the Johnson ad “Confessions of a Republican,” in which a GOP voter explains why he can’t support his party’s nominee, and even cast the same actor to recite his old script, this time about Trump.

But could the spectacular climax of the cinematic campaign of 2016 be Clinton matching Johnson’s 1964 feat? Probably not. With today’s polarized electorate, Clinton is extremely unlikely to be able to match Johnson’s 61.1% of the popular vote.

Still, with less than three months to the election, and with a map of “battleground” states that includes places like Georgia, Arizona and Utah, an Electoral College landslide is not out of the question for Clinton. LBJ’s experience offers the Clinton camp some key takeaways on how to not only win this year, but also win big:

America doesn’t love you… and that’s O.K.: Johnson’s presidential campaign had few illusions about what was driving their big polls numbers in the fall of 1964. “FACT,” read a memo from Johnson aide Jack Valenti to his boss, “Our main strength lies not so much in the FOR Johnson but in the AGAINST Goldwater.” Sure, Americans approved of the sturdy leadership Johnson had provided in the months following Kennedy’s death, but few voters felt a deep emotional connection to him. His aides noted, uneasily, that responses to Johnson’s convention speech had shown only “moderate undifferentiated approval,” a phrase you could imagine floating around the halls of the Clinton campaign.

Luckily, Johnson’s team stuck with its central message: “The stakes are too high for you to stay home.” Similarly, the Clinton campaign has to convince the country that their candidate is the only acceptable choice in a two-way race. Her base may worry that a mushy, moderate campaign message will mean a mushy, moderate governing agenda. But Johnson’s example shows that won’t necessarily be the case. After running a campaign with far less substance than Clinton’s has had, he went on to enact the most ambitious progressive domestic program of any president since FDR.

Hold your nose and make nice with press: Like Clinton, Johnson was deeply wary of the press. Nevertheless, his aides understood that the press had settled on a storyline for the campaign, Crazy Barry vs. Indomitable Lyndon, and for that story to work, Johnson’s aides knew they had to keep reporters supplied with good access, color and quotes. The Clinton campaign, famously reluctant to hold press conferences, could profit from following Johnson’s lead.

Don’t sweat the October Surprise: In October of 1964, newspapers reported that Walter Jenkins, one of Johnson’s closest aides and a married father of six, had been arrested while sexually engaged with another man in the bathroom of a Washington YMCA. A riveted political establishment expected public outrage and an accompanying bounce for Goldwater in the polls. But voters simply shrugged.

Democrats, who’ve been haunted this year by the DNC hacks, should expect a similar surprise three our four weeks out from Election Day. But absent a truly shocking revelation—a high bar in 2016—last-minute bad news for Clinton probably won’t make much of a difference.

Don’t expect the landslide to last: There’s little correlation between winning the White House big and having big successes once you’re there. Johnson’s experience after 1964 offers a particularly poignant example of how fleeting a landslide can be. Four years after his historic victory—following a term plagued by violence at home and abroad—Johnson was so unpopular that he did not seek reelection.

Which speaks to perhaps the most important lesson Johnson can offer Clinton: Drawing an opponent like Trump is a rare strike of good fortune. Savor it. You’ll probably never be so lucky again.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Jonathan Darman is the author of Landslide: Lyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan At the Dawn of A New America.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com