The flood of advertisements for and against candidates at the local, state and national level has already begun. Whether attacking a political opponent, outlining a vision for leadership or celebrating a candidate’s achievements, political advertising seeps into email inboxes, news feeds and television screens. While Hillary Clinton’s team has charged ahead in the “air wars,” the Trump campaign—having recently announced it will invest heavily into digital marketing efforts to revamp its message and rebrand its polarizing candidate—has also launched its first general-election television ads.

Interestingly enough, this tradition of political advertisement began at time similar to our own, when a GOP nominee for president, whose celebrity status made up for his lack of political experience, grappled with how to approach a new technology to break the Democratic dominance of the White House.

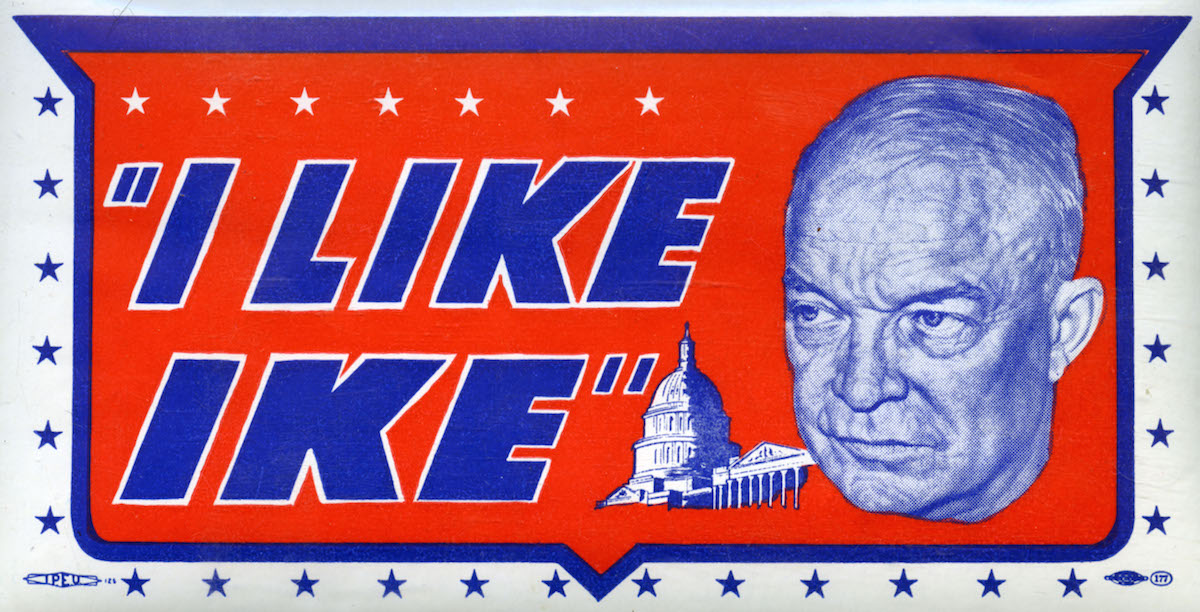

In the summer of 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the general who led American forces to victory during World War II, met with advertising hotshot Rosser Reeves to discuss how to translate his military fame into political gain. The slick salesman sold the candidate on a dramatically new approach to television: a 30-second advertising spot campaign. Though television ownership was skyrocketing, Ike initially resisted. Could he really articulate his qualifications and policy stances in 30 seconds?

Eventually he said yes, and advertising executives and motion picture producers joined together to launch “Eisenhower Answers America!” Led by showmen from Hollywood and Madison Avenue, the spot campaign showcased the potential of advertising, entertainment and political consulting in presidential politics. His team’s media innovation nationalized a celebrity political culture and ushered in the modern candidate-centered campaign.

Though commonplace today, the adman and entertainer were firmly on the periphery of American politics prior to the 1950s. Both industries were frequently looked upon with disdain for the way they manipulated public emotions. That had begun to change in the 1920s. Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover recognized that professional showmen had knowledge from which they could benefit, and listened to the advice of adman Bruce Barton on how to use public-relations tools to gain a political edge. In the 1930s and ‘40s, Franklin Roosevelt continued to experiment with advertising, going so far as to bring in Hollywood as well. Jack Warner, Humphrey Bogart and Orson Welles crafted entertaining radio ads that sold Franklin Roosevelt’s 1944 reelection bid with star power.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

But, in 1952, the new technology of television captured both the interest and the fears of the American public. Was it a tool for manipulation or an opportunity for civic engagement?

When that year’s election came around, the Democratic candidate saw television programming, which was produced by advertising companies, as antithetical to democracy. Adlai Stevenson had little patience for any technology that emphasized the importance of image so, per his instruction, the DNC purchased half-hour blocks of television time to give the Illinois governor plenty of time to explain his stance on the issues. To afford such time, the campaign opted for late-night hours, when viewership was low.

Rosser Reeves, however, convinced Eisenhower that television represented the “essence of democracy.” He successfully pitched his idea for 20- to 30-second advertisements that could inform viewers quickly and in a catchy manner. The political newcomer acquiesced, though Ike would frequently grumble his frustration in production studios. “Why don’t you just get an actor?” he once asked, exhausted after a day of filming.

But the storyboards that advertisers put together, with Ike at the center, connected the candidate emotionally to television viewers. Airing in what Reeves called the “humble spot,” between popular shows when audience viewership was high, these ads introduced disgruntled Democrats and independent voters to the Republican nominee at a time when they were enjoying their favorite entertainment programs.

And it worked. These ads helped Ike not simply convert Democratic voters, but more importantly, activate nonvoters. Traditional Democratic voters, organized by unions or city bosses, were unlikely to vote for him—but media consumers would, especially if he ran a campaign designed for television and targeting the merits of the likeable, affable WWII hero.

When accepting the Democratic nomination in 1956, Eisenhower’s challenger, again Adlai Stevenson, ramped up his criticism of the president for surrounding himself with advisers who “believe that the minds of Americans can be manipulated by shows, slogans and the arts of advertising.” That year, Republican advertisements varied between 30-second spots and five-minute programs. The catch: the five-minute programs frequently ran at the end of popular entertainment shows, with a seamless transition into the ad. Ike’s White House media adviser, actor Robert Montgomery, hosted his own television show, Robert Montgomery Presents, where he invited celebrities to discuss their upcoming films. During the fall of 1956, the last five minutes of the show, purchased by the RNC, ended with a discussion between Montgomery and his guests about the merits of the president. Conveniently these entertainers were all “pro-Ike.”

Though Stevenson abhorred and resisted the commercialization of the electoral process, his Democratic successor, John F. Kennedy did not. In fact, this son of a Hollywood executive—Joseph P. Kennedy ran a small studio in the 1920s—hired Jack Denove Productions to follow him around the primary trail to capture crowd shots and interactions with voters. Kennedy’s team then turned this footage into spot advertisements to generate excitement for upcoming campaign stops. Kennedy expanded Eisenhower’s strategy, winning the nomination with a privately funded media team that used TV and radio spots to transform him into a celebrity to gain political legitimacy.

Since the 1920s, new technology—radio, motion pictures, television and now social media—has transformed the political landscape to make show-business knowledge increasingly central to political success. The early 20th century wheeling-and-dealing city boss who leveraged patronage for power has been replaced by the modern political consultant, who plays media games to mold public sentiment. For better or worse, electoral battles are waged not in smoke-filled rooms, but in studio-control rooms, and deploying “shows, slogans, and the arts of advertising”—while it may not be the essence of democracy—has become ingrained in the democratic process.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Kathryn Cramer Brownell is assistant professor of history at Purdue University. She is the author of Showbiz Politics: Hollywood in American Political Life. which explores the use of Hollywood styles, structures and personalities in U.S. politics over the 20th century.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com