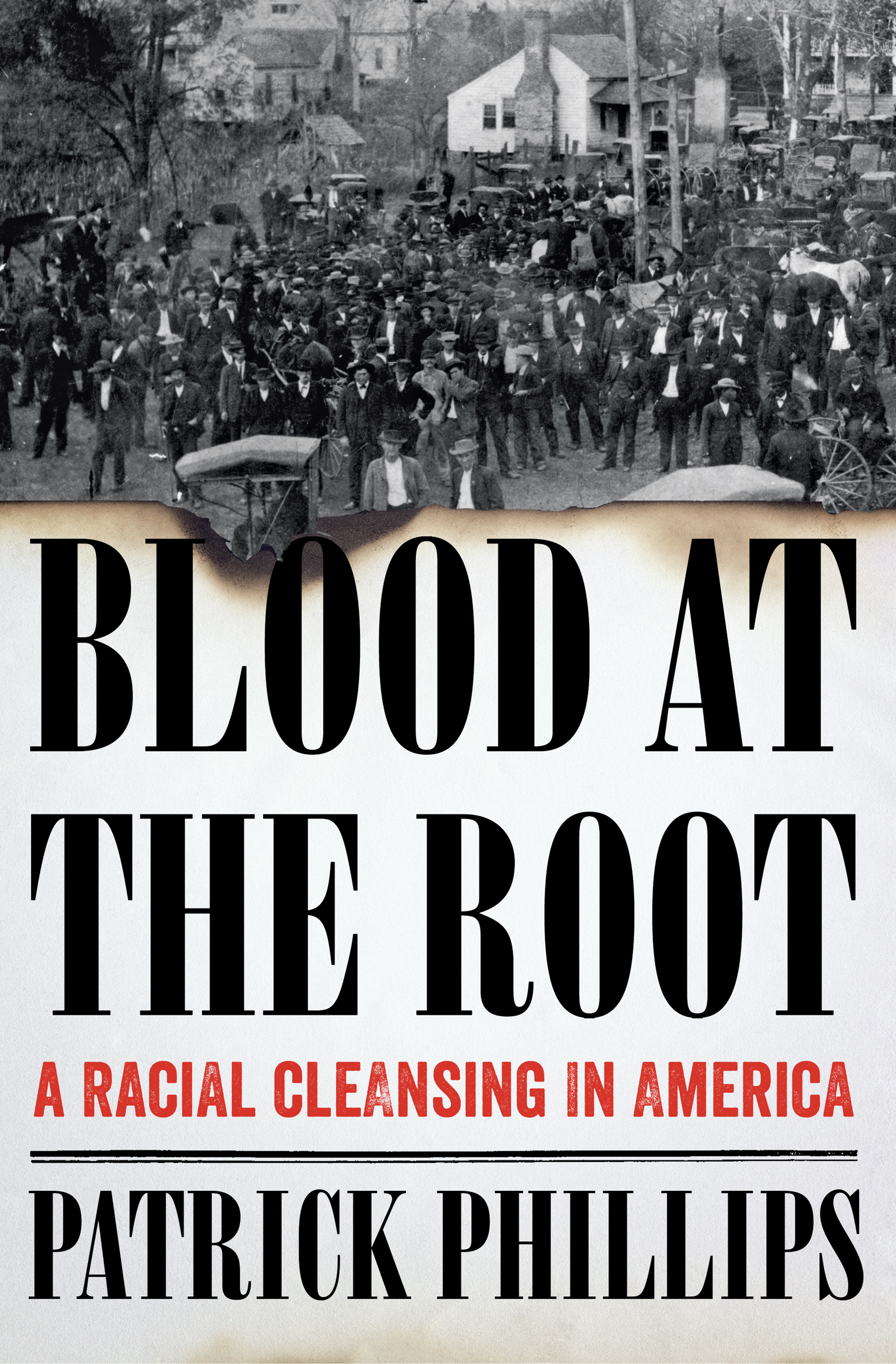

Patrick Phillips is a poet, translator and professor at Drew University, as well as a Guggenheim and NEA Fellow and the author most recently of Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America.

Since I was a child I’d heard the legend, usually told by another school-boy in the backseat of the bus. It was a kind of tall tale, about how “a long, long time ago” white people in Forsyth County, Georgia, had “run out” out all the black people.

When I was growing up there in the 1970s and ’80s, Forsyth was still a “white county,” but there were no signs anywhere that African Americans had ever really lived there, and my teachers at Cumming Elementary never said a word about an exodus of black residents. I couldn’t find a single book about it in the County Library, and so the expulsions always seemed to me like only a kind of myth. Probably, I remember thinking as a kid, it was all just made up.

When, decades later, I finally began researching that old ghost story, I found that I had been ignorant of my home’s real history—not because the truth was hard to find, but because no one I knew had ever bothered to really look. At the University of Georgia, I read contemporary newspaper accounts of the fall of 1912, when the murder of a young white woman led locals to lynch a black man on the town square, then hang two teenagers after a one-day trial. In the wake of the executions, gangs of armed white men rampaged all through September and October, determined to punish the entire African-American community for what the papers called “a black rebellion.” They fired into sharecroppers’ cabins and set fire to churches, until all 1,098 African American residents had fled the terror. For nearly a hundred years, descendants of those original night riders had used violence and intimidation to keep Forsyth “all white.”

And yet, when I finally went back home in 2014 to search for traces of the vanished black community, there was no sign anywhere of the racial cleansing that had transformed Forsyth in the years just before World War I. No plaque marked the corner where hundred of locals had fired their pistols into the corpse of Rob Edwards as it hung from a telephone pole. There were no photographs in Historical Society of state militia troops marching through town to quell the mobs. And nowhere among all those portraits of Confederate soldiers was there a picture of Levi Greenlee or Joseph Kellogg, black leaders who had owned large farms in the county, and who founded two of its most prominent black congregations.

Instead, gazing out over the square was a larger-than-life bronze statue of Hiram Parks Bell, who was a member of the Confederate congress and then the U.S. House of Representatives. Forsyth’s most celebrated native son, “Colonel” Bell was also an unrepentant white supremacist. While serving in Washington he had railed against the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which gave African Americans citizenship, calling it a “legislative folly… intended to harass and humiliate the white people.” Bell was proud to call himself one of the “able and patriotic” men who, after expelling elected black Congressmen in the 1870s, “established a Constitution that secured white over black domination.”

While I was once just as blind as everyone else in the county, when I finally learned the real history of my home, I began to see traces of the vanished black community everywhere I looked. When I passed a sign for “Shiloh Road” I thought of the African American parishioners who had worshipped at Shiloh Church before it was burned to the ground. When I drove over Brown’s Bridge and into neighboring Hall County, I pictured hundreds of families fleeing the nightriders on foot, crossing the old wooden bridge with only what they could carry. And yet, all around me, it was clear that the residents of Forsyth were still deep in their sleep of forgetfulness. In the new millennium, the northward spread of the Atlanta suburbs has brought unprecedented wealth and prosperity to the foothills, and most white people of the county, enriched by the soaring property values, have long ago written the racial cleansing completely out of mind.

In 2016, as protestors all over the country ask Americans to simply acknowledge that “Black Lives Matter,” our nation is profoundly divided on the subject of race. And there are clearly no easy solutions. But a start, surely, is for all of us to turn and face the real history of our homes, and to finally reject the sanitized, de-racialized stories many Americans tell themselves about the towns and cities where they live. Few “white” places came to look the way they do now without acts of bigotry—from overt purges like in Forsyth, to more covert forms of racism like red-lining, discriminatory lending and illegal forms of bias in housing and employment. To dig into the recent past of most American hometowns—like my own—is to find that painful truth buried just beneath the surface of all those immaculate green lawns.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com