By covering political scandals such as the Teapot Dome bribery incident, and giving ink to poker-game shootings and boozy brawls, the New York Daily News—America’s first successful tabloid paper—dredged the depths of ’20s and ’30s culture, replacing staid journalism with lurid photos and a shocking, sleazy sensibility. In the process, it offered narratives tailor-made for the burgeoning world of pulp fiction—and the films noirs that ensued.

Novelist James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice, for instance, were based on the murderous machinations of Ruth Snyder, who killed her husband with the help of her lover. Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest and David Grubb’s The Night of the Hunter are among other works that were “ripped from the headlines.”

The tabloids also influenced the distinctive look of the films that were inspired by these fictions. In the 1930s, flashbulbs, new cameras, and faster shutter speeds allowed newspaper photographers to ply their trade pretty much anywhere, anytime. The result: a daily documentation of the previously unexplored underbelly of urban existence. Even the look of these photos added to their impact: “The lack of naturalness in these pictures was not a shortcoming but a source of their melodramatic power,” wrote John Szarkowsi in Photography Until Now. “It is as though terrible and exemplary secrets were revealed for an instant by lightning.”

Historian Luc Sante has even made a connection between specific photos and subsequent films. “A 1945 picture of a slaying at Tony’s Restaurant, with its violent angle, oblique window approach, and mocking use of advertisements, anticipates the blunt force of Anthony Mann’s T-Men . . . and the jazzy chill of Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly,” he wrote, adding that a 1930 shot of a homicide at New York’s Chinatown People’s Theater reflects the look of Howard Hawks’s 1932 film Scarface.

No photographer was more identified with tabloid journalism than Arthur Fellig, a.k.a. Weegee, who made his name freelancing out of Manhattan’s police headquarters. (“Here was the nerve center of the city I knew,” he wrote, “and here I would find the pictures I wanted.”) With relentlessness and relish, he covered auto accidents, deli holdups, gambling joints, and “jumpers,” turning a nation of readers into rubberneckers even as he imbued ghastly Gotham with a kind of poetry. “Crime was my oyster,” Weegee said, “and I liked it.”

Weegee’s first photography book, 1945’s autobiographical Naked City, inspired the 1948 noir film The Naked City. Reflecting the documentary style that gave many noirs their sense of authenticity, The Naked City was shot entirely in New York City and ended with the iconic line “There are eight million stories in the naked city—this has been one of them.”

The success of the book and film led to a minor acting career for Weegee. In a self-reflexive Hollywood hall of mirrors, he appeared in a few of the films his work had helped shape: 1949’s classic boxing noir, The Set-Up, and 1951’s forgettable remake of Fritz Lang’s proto-noir M. Even as the photographer disdained L.A.’s natives as “zombies” (“they drink formaldehyde instead of coffee, and have no sex organs”), he was collecting material for his next book: Naked Hollywood, naturally.

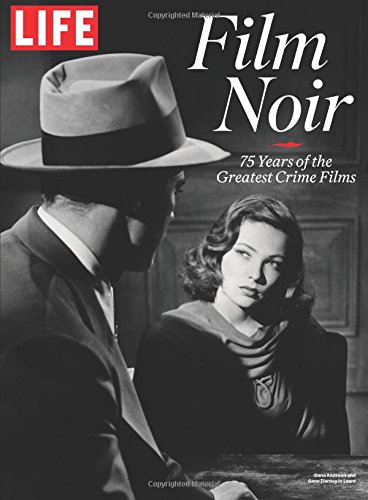

Read more in LIFE’s new special edition Film Noir: 75 Years of the Greatest Crime Films, available on Amazon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com