This essay originally appeared at The74Million.org, a non-profit education news site. Sign up for The 74 newsletter.

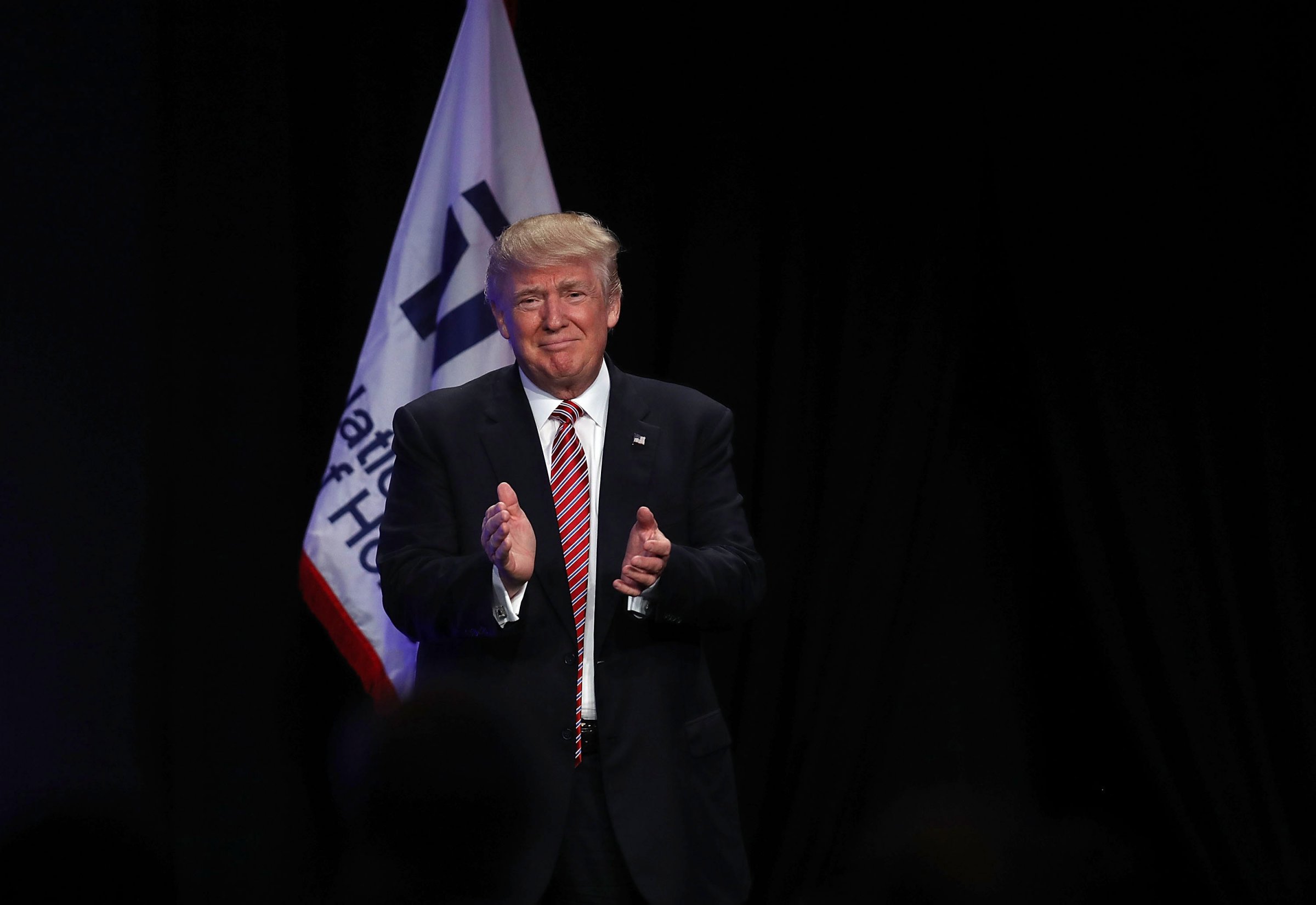

News and essays about the Republican nominee for President, Donald Trump, are increasingly focused on core questions of character, as he appears more socially and emotionally irrational by the day. His most recent scandalous remark came last week during a rally in which he insinuated Hillary Clinton could be assassinated.

But it’s not the first time outrageous comments have called his character into question. (It wasn’t even the only scandalous remark he said last week; a couple days later, he declared President Obama the founder of ISIS). During the primaries, Trump took what we know, or what we thought we knew, about the value of certain social attitudes and behaviors, and turned it around on us. Rude and insulting became the gauzy rejection of “political correctness.” Subterfuge at the expense of others was sound business practice. Bullying was welcomed as long-awaited “straight talk.”

Trump seemingly amassed a following not in spite of, but because of his tendency to run afoul of societal norms, taking us through the looking glass, like Alice, to an upside down and backwards world of alternative reality of decorum.

It’s not pretty. And for parents and teachers, it’s a societal shift that’s not easily explained to our kids.

In fact, there’s now massive incongruity between what has played out before our eyes in this political season and what our schools have doubled down on in recent years, in terms of a growing emphasis on character — or that “something other” in our children. There is a growing body of evidence that factors such as emotional regulation, frustration tolerance, gratitude, conflict resolution, and a willingness to explore new ideas are deeply connected to learning and social development outcomes.

These qualities fall under a rather dizzying array of names, including “personal competencies,” “social emotional skills,” and “noncognitive/nonacademic variables.” All go beyond the cognitive and academic knowledge typically measured and reported on in schools and, many thought leaders argue, get to the heart of what matters most for kids and for life. Policymakers, via ESSA, have provided the rationale and flexibility to consider embedding these skills into statewide accountability frameworks. The work is nascent yet exciting, and as I write about here, considerable caution should be taken as we refine our ability to measure and capture valid evidence of these skills.

But given Trump’s larger-than-life demonstration of the counterfactual, are these efforts for naught? No, and in fact, I’ll argue they are more important than ever.

Research tells us that behaviors exhibited by Trump, especially when bundled together , may lead to long-term negative results for individuals, including deficient social, academic, and occupational functioning and, in some cases, even incarceration. More broadly, these individuals can cause sweeping harm through, for example, financial exploitation, theft, and emotional abuse of others. The abbreviated list below of characteristics of antisocial personality disorder shows alarming parallels to persistent patterns in Trump’s behavior, not only based on what we see now, but also based on what we can glean from his childhood:

Donald Trump is a very human example of a statistical outlier. He is not typical; in fact, he is an example of a child that seems to have slipped through the cracks in terms of consequences and social learning, perhaps due to the mitigating factors of wealth and privilege. His strengths in other areas, including knowing his audience and capturing attention, have carried him forward, significant social and emotional limitations notwithstanding.

For educators, Trump provides a peek at character run amok in one individual. But many individuals, together comprising a vocal and active constituency, paved the way for him. We must lead students back through the looking glass to a world of reason. In addition to emphasizing the value of individual character traits and social emotional skills, we can also teach children how to recognize when others go awry and become outliers, because we not only see it happening now, we should expect that it can and will happen again.

Trump’s ascent shows the importance of cultivating children that have the capacity to be sound consumers — and analysts — of the behavior of others.

Trump’s caustic nature may well catch up to him. In addition to being called out on his behavior as a candidate during this general election season, real consequences related to his character and practices prior to his candidacy loom. Whatever happens with Trump, we will be left with an understanding of the collective mindset that allowed for him, those that championed him and those that proved willing to look the other way, many of whom should have known better.

Children grow into adults that will coalesce into our next constituency. We need them to recognize social deviance and, if unable to demonstrate it has consequences, at least limit opportunities for those individuals.

As educators press on with their efforts in this imperfect world, we at least now have a very clear vision of the stakes at hand, and a contemporary sense of how important this work is for our students — and our future.

Allison Crean Davis is a contributor to The74Million.org and a senior adviser at Bellwether Education Partners, focusing on issues related to evaluation and planning, predictive analytics, extended learning opportunities, and Native American education.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com