Year after year of record heat largely due to man-made global warming has hit hard across the globe. And nowhere have the impacts been more devastating than in the Arctic where temperatures are rising more than twice as fast as the global average and ice is quickly disappearing.

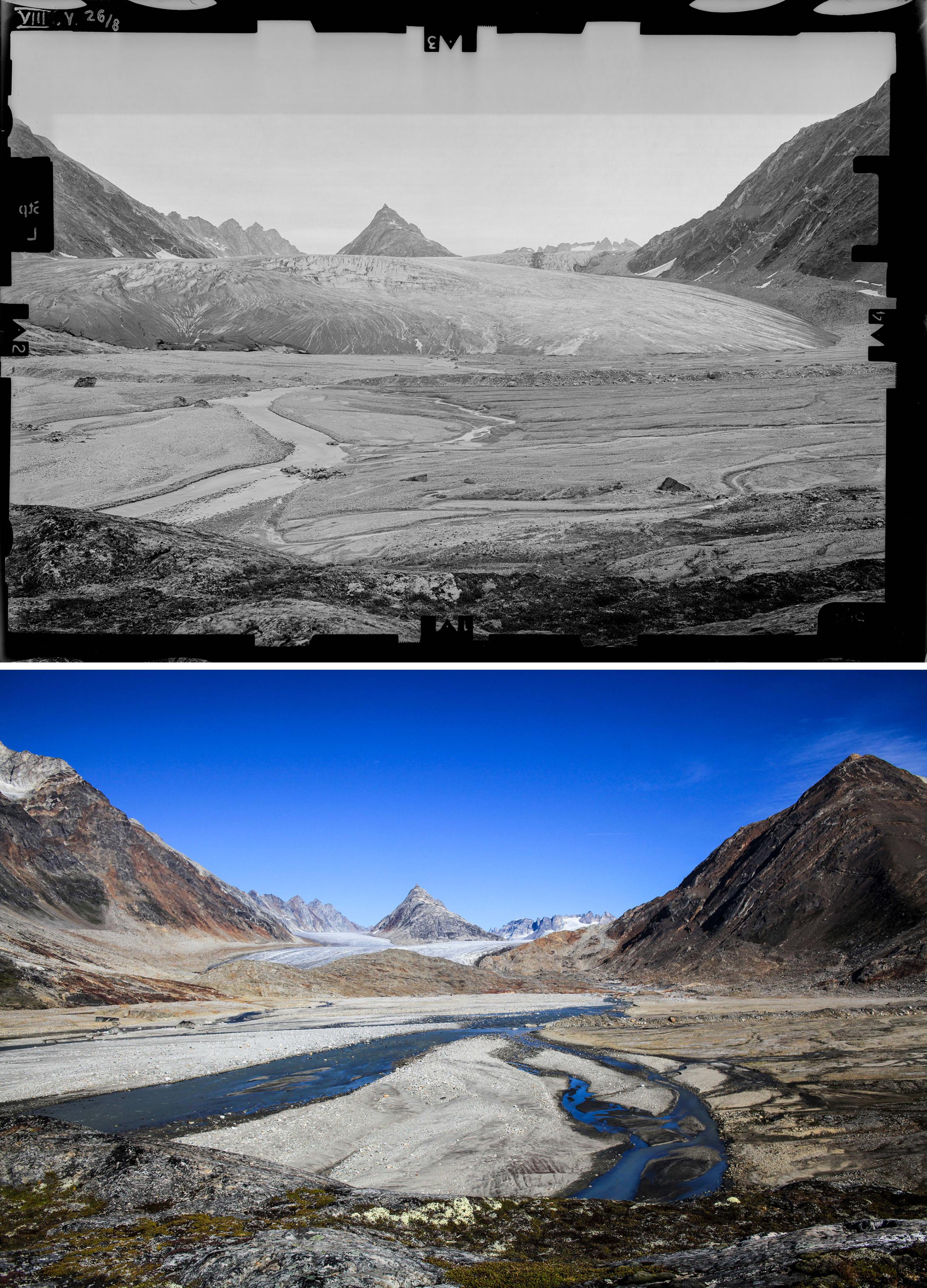

Photos taken by a research team from Denmark capture how warming has hit glaciers in Greenland, where ice melt has been occurring at a faster rate than ever in recorded history. Researchers captured the images, published in the book The Greenland Ice Sheet, in the exact location their predecessor had taken photos eight decades prior as temperatures had just begun to warm. Side by side, the images offer a stark comparison showing vast areas once covered in ice now empty land.

Take the Mittivakkat Glacier on the island’s southeast coast. A black-and-white image from 1933 shows the glacier occupying the entire a valley. In an image from 2010, the glacier has completely disappeared.

“Climate change is particularly evident here and its consequences for people and nature are considerable,” said Ralf Hemmingsen, rector of the University of Copenhagen in the book’s foreword, “both for Greenland and the rest of the world.”

Scientists have understood for sometime how climate change is causing ice melt in Greenland. Satellite measurements taken since 1979 have shown a 12% decline in sea ice per decade, according to a Nature report. But a lack of earlier record keeping and satellite measurements has presented a challenge for scientists who hope to understand how ice levels have changed over time in Greenland. Now, scientists who study glaciers are using the photo comparison to improve their understanding of how ice levels have changed over time, according to a news article in the journal Nature.

Ice loss in Greenland presents challenges for the small communities located on the island, technically an autonomous part of Denmark, but ice melt also has profound effects across the globe, most significantly contributing to sea level rise that threatens cities along the coasts. Nearly 700,000 cubic miles of ice are located on Greenland’s ice sheet, covering three quarters of the island. Scientists say that 23 feet in global sea level rise would result if all that ice melted, drawing many cities across the globe.

It’s still possible to avoid such a catastrophic scenario, but scientists say action is needed fast. Current warming results from greenhouse gas emissions emissions from years and decades ago. No matter what we do now, the globe will continue to warm of the foreseeable future—and Greenland’s ice will continue to melt.

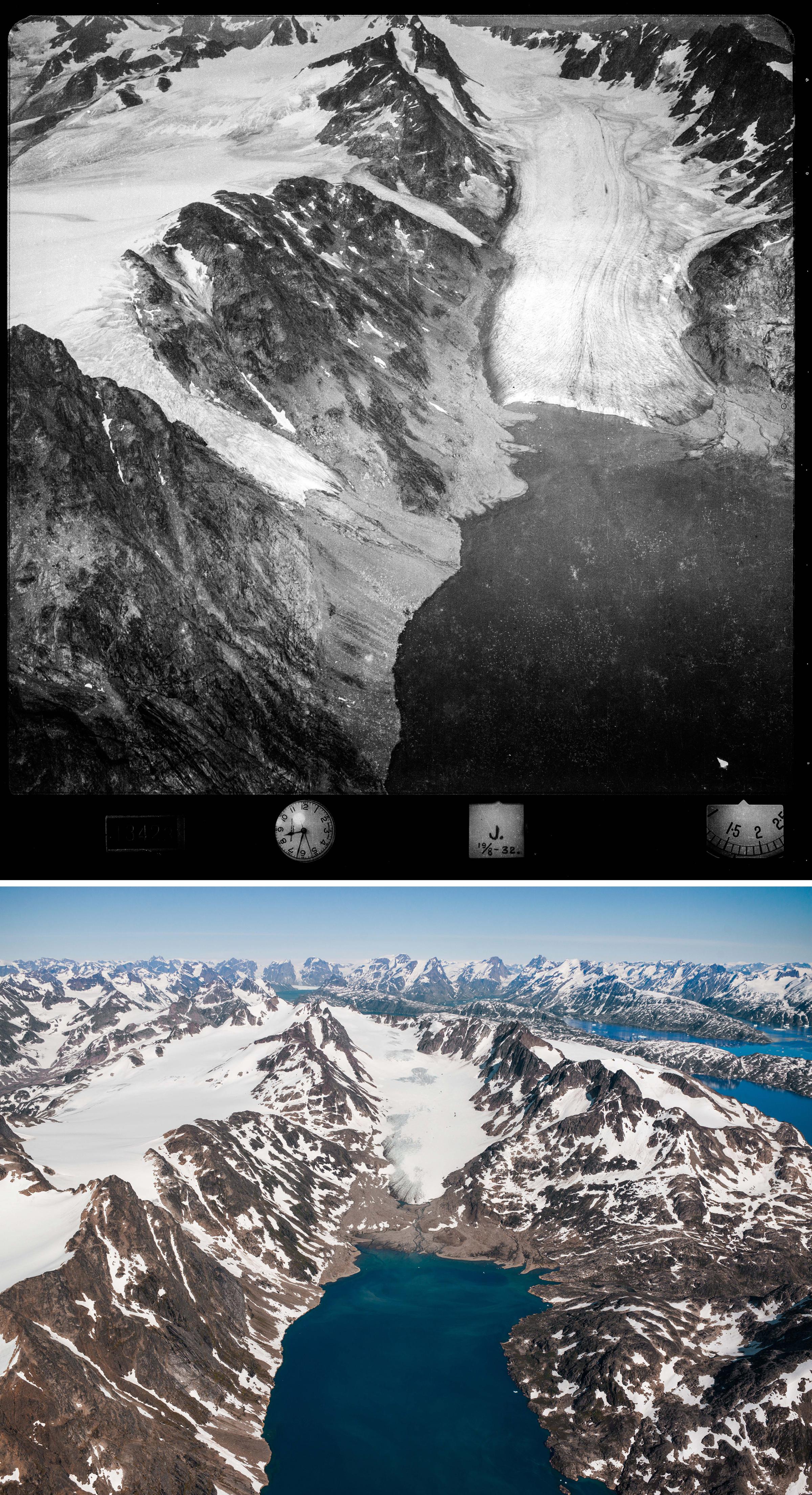

Stauning Alper

Gully Glacier, in Alpefjord, occupied almost the entire fiord in 1933. Because of the large amount of precipitation in this area, glaciers develop anywhere the snow is not blown away.

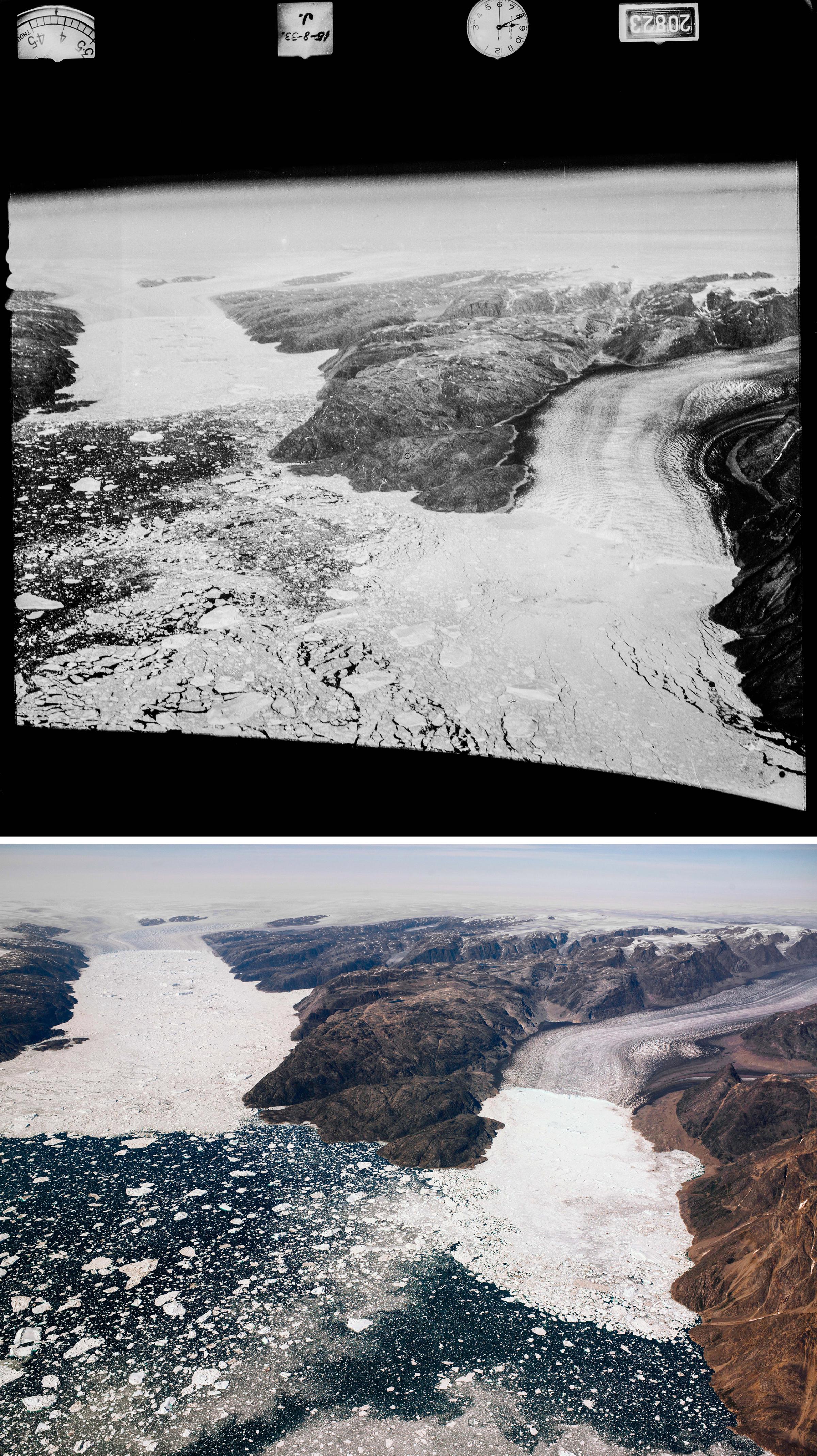

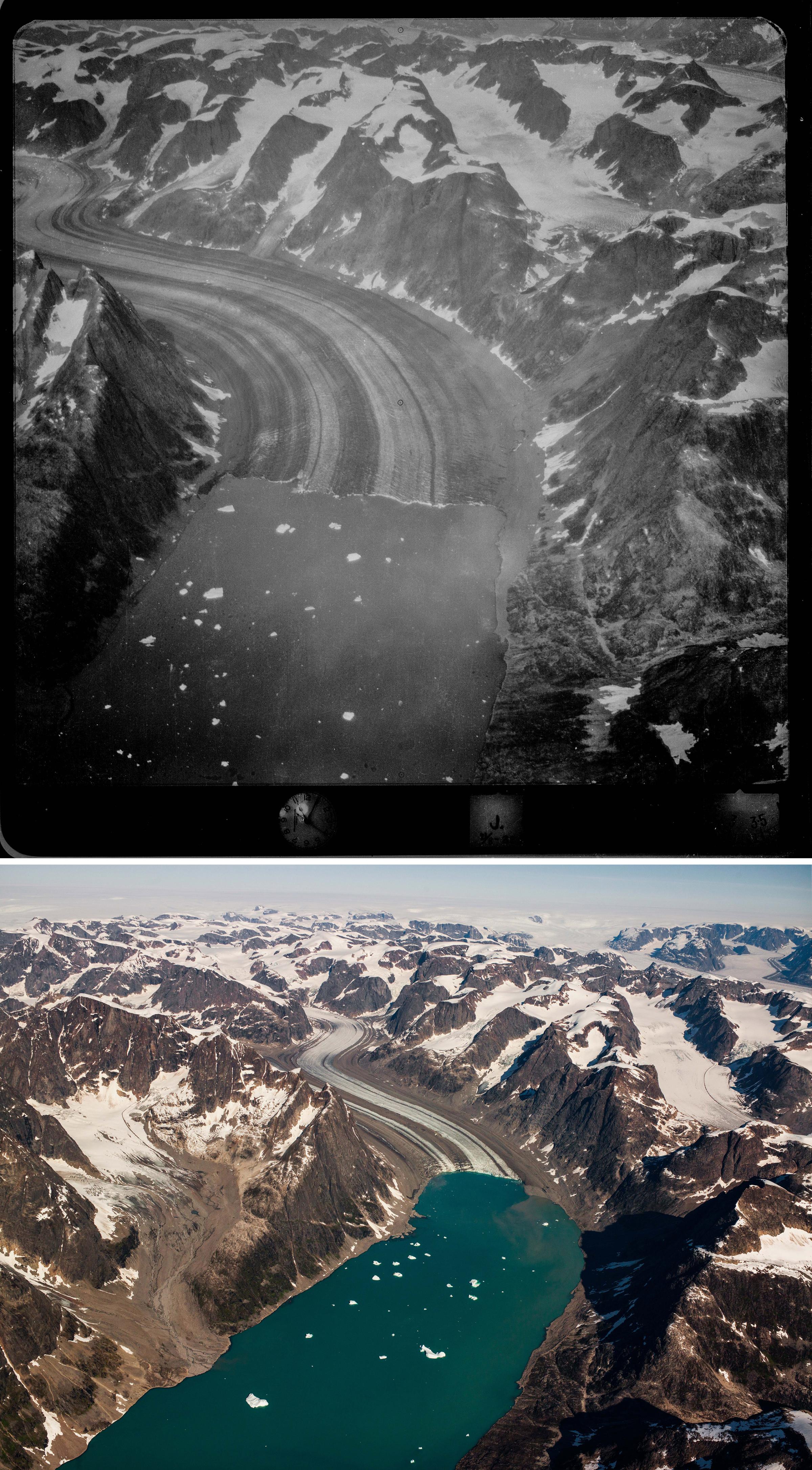

Sortebræ

Sortebræ ends in the sea on the Blosseville Coast, a rugged stretch of coast feared by sailors. Sortebræ is a ‘surging glacier’, a special type of glacier that, because of surrounding rock conditions, periodically advances very rapidly.

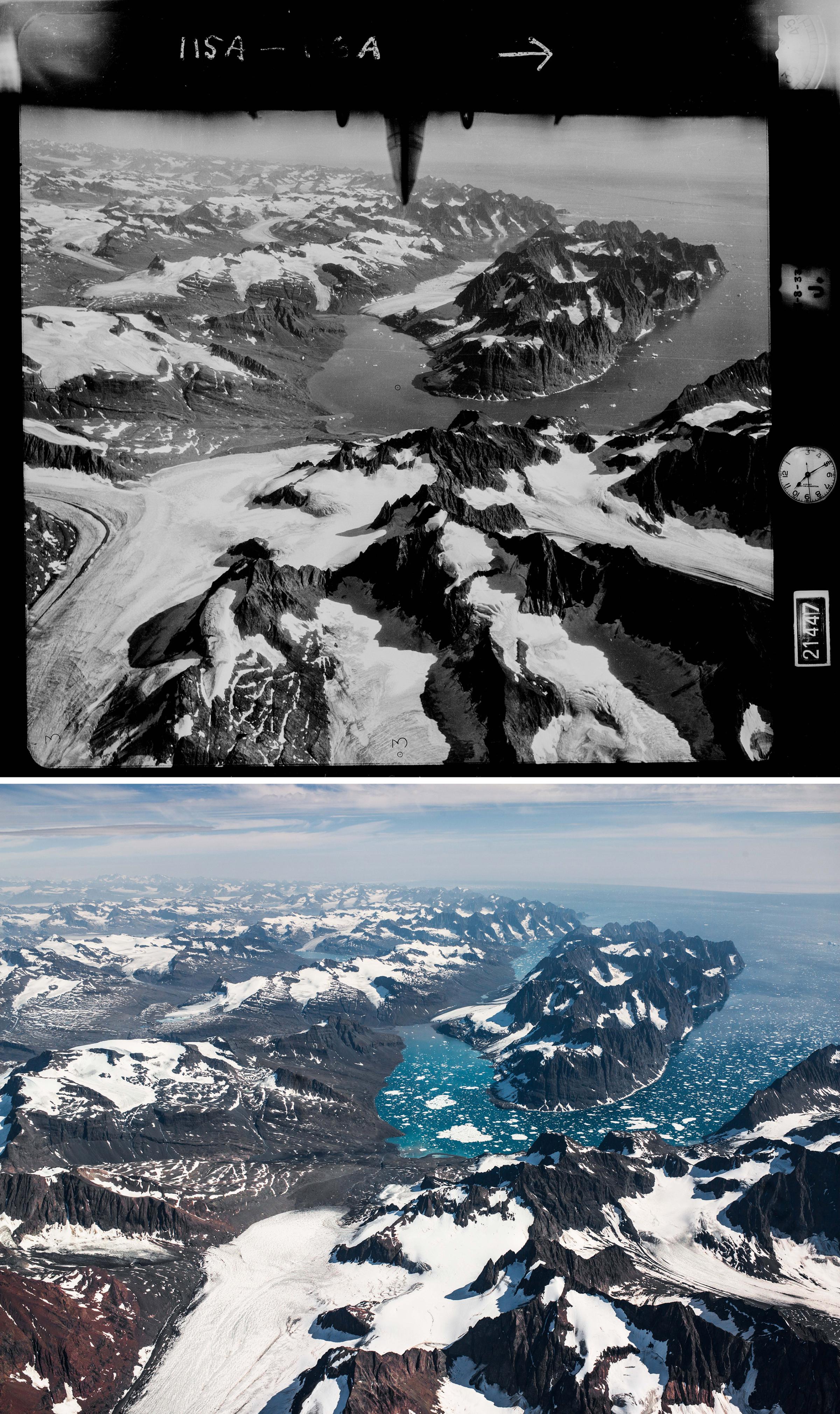

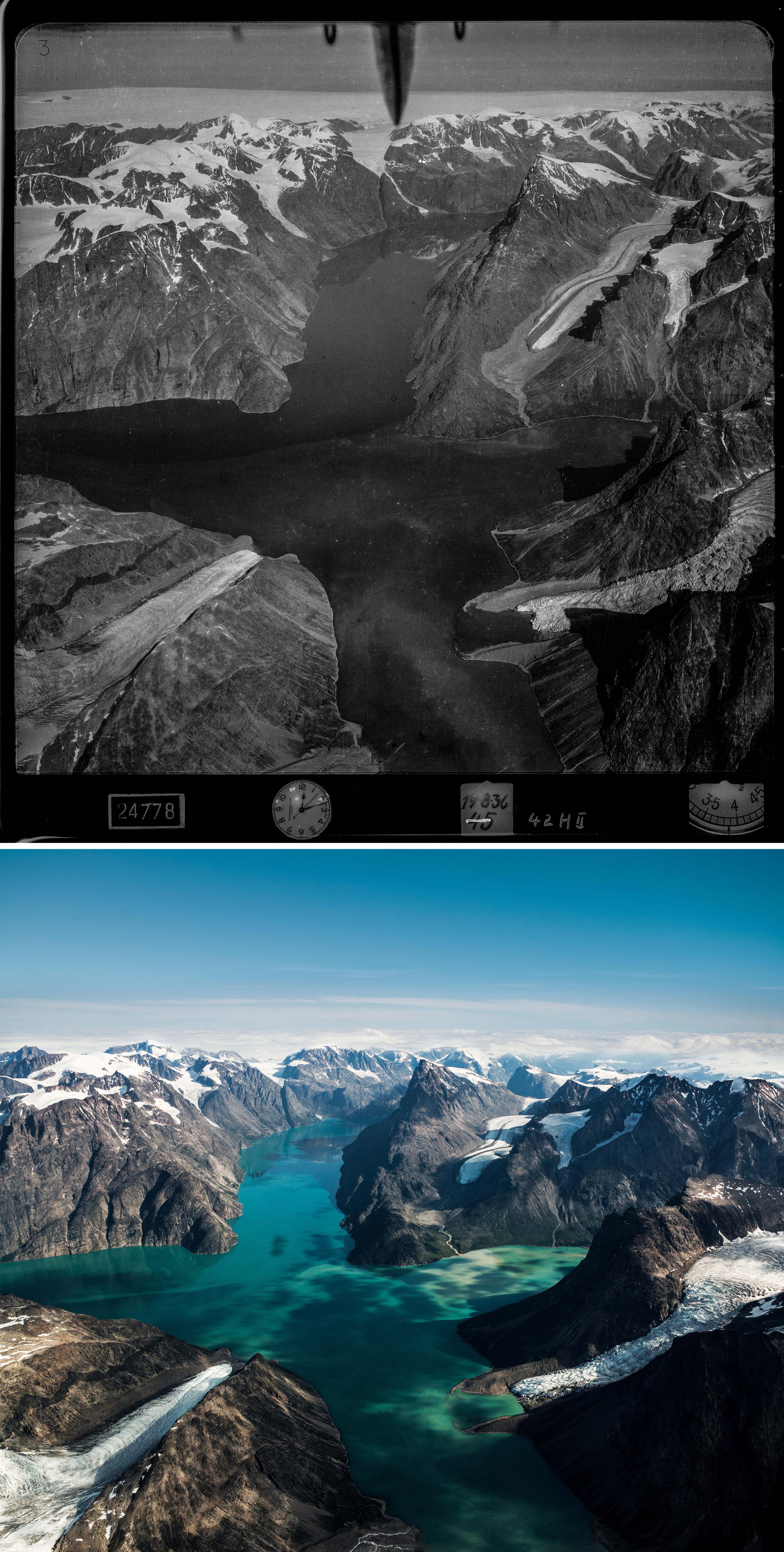

Miki Fjord

This area was used as an anchoring location during the original 1933 expeditions, as the fjord provided a natural harbor. All of the glaciers in this area have retreated and some have disappeared completely.

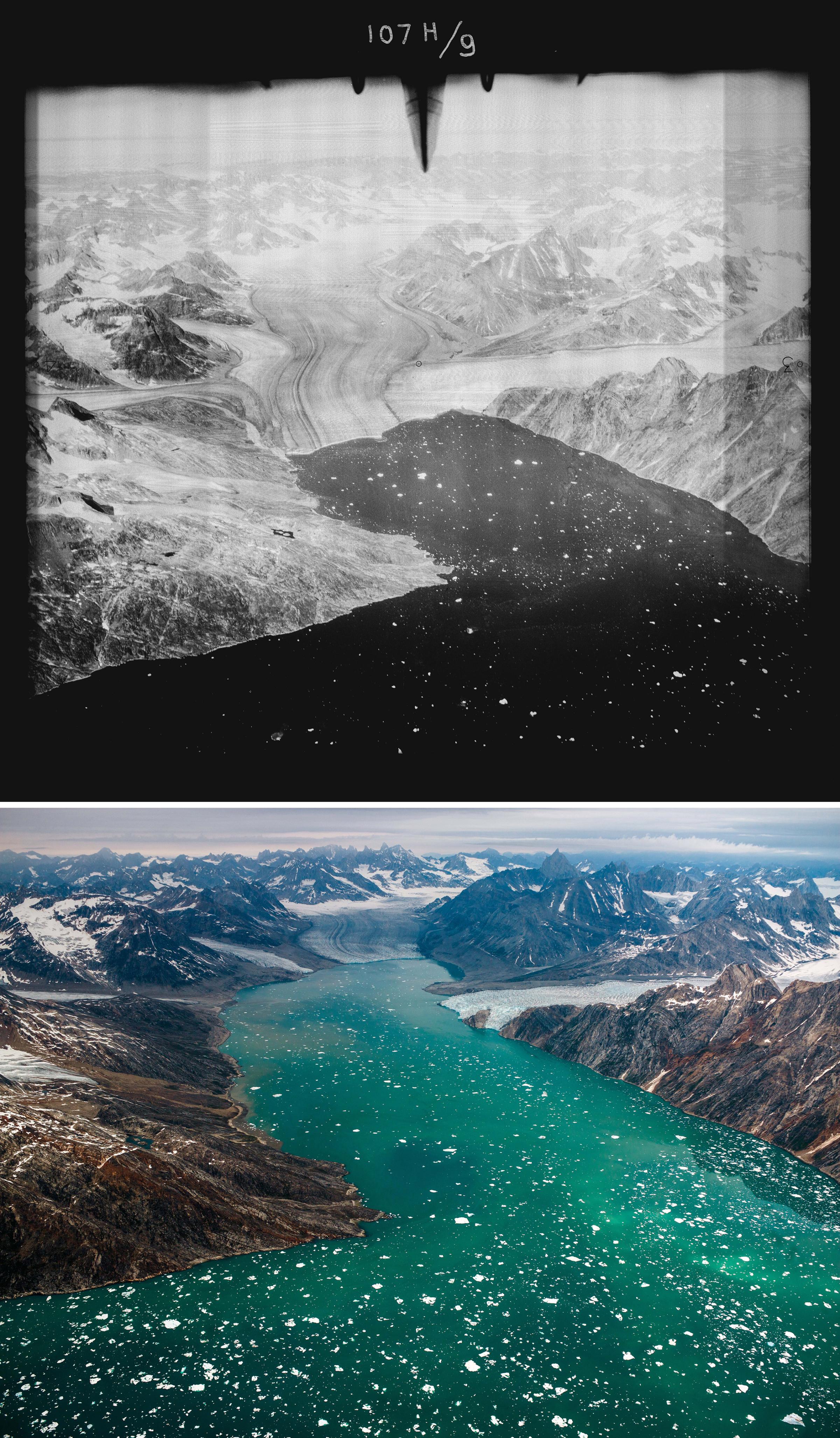

Karale Glacier

The Karale Glacier, located just north of Tasiilaq, the largest town on the east coast of Greenland, is almost three kilometers wide and has retreated more than 6 kilometers over the last 80 years.

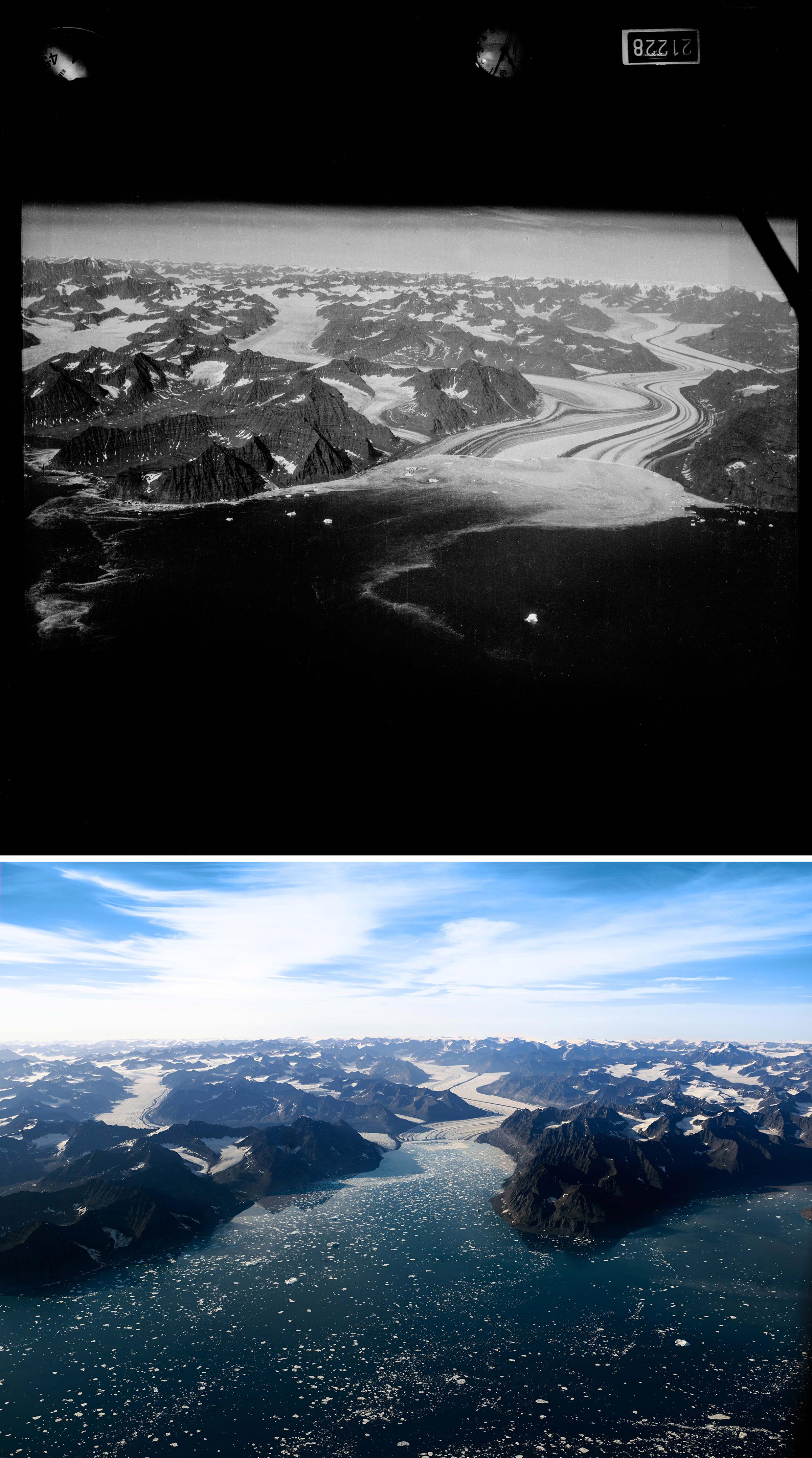

Midgaard Glacier

The front of this glacier has retreated about 30 kilometers and an entire fiord has been exposed, making this ones of the places where the effects of melting are clearest. This glacier has been continuously retreating since the first picture was taken in 1933, but the rate of melting has increased through recent decades.

Helheim and Fenris

Fenris Glacier can be seen here on the right. Helheim is visible in the background.

Tunu Glacier

This glacier has also changed dramatically since 1933. It has retreated about 1500 meters, leaving the valley almost ice free.

Skjoldungen

Since 1932, much of this glacier has calved into the sea, leaving it now entirely based on land. The small glacier on the left of the 1932 picture has also retreated drastically and its front is now high in the mountains on the side of the fiord.

Snehatten

This striped offshoot of Snehatten, a mountainous area on the southeast coast, has retreated by about a kilometer.

Evighedsfjord

In these high mountains, glaciers are fed by the ice caps. Melting here is not as extensive as elsewhere along the coast. The fronts of most of the glaciers here are now located a couple of hundred meters further back than in 1936.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com