As evening fell on the first day of the 1971 prisoner uprising at Attica, a request was granted for a doctor to be allowed into D Yard, an area that was then under the control of the prisoners. That physician was Dr. Warren Hanson, a surgeon at a hospital 15 miles south of the prison. Shortly before midnight, Hanson entered Attica.

After being given assurance of safe passage by the prisoners in the DMZ, Hanson was assigned a personal security guard who told him, “Doctor, I am responsible for your safety. . . . I don’t want to be holding and pushing you around [so] why don’t you hold my arm and let me kind of lead you, and you just follow me.” Once in D Yard, Hanson saw two long lines of prisoners who were wearing white armbands, had linked elbows, and faced each other. These men had, in effect, formed a secure human tunnel for him to walk through. He was very grateful.

Hanson met with the leadership group, and then was escorted to the medical station, which consisted of three tables and a chest with some medications and bandages. After being briefed by the prisoners’ medical team, Hanson headed over to the hostage circle. The hostages, who were still surrounded by the security team of Black Muslims, were huddled together in an oval-shaped space, some of them sitting up, others lying down. By now the hostages had been blindfolded for almost ten hours and Hanson found them in a state of severe emotional distress. He did his best to try to calm them down, and was “pleased to find that they were in quite good shape.” The prisoners had already tried to tend to the hostages, in several cases splinting possible fractures as well as doing some emergency suturing, and while a number of the hostages had various wounds and injuries, none of them were life-threatening.

Although the prison administration had sent Dr. Hanson in to check on the health of the hostages, when the leaders in D Yard asked him to look at the prisoners who were also in need of care, he readily agreed. Returning to the medical station, he held a sick call attended by approximately twenty-five to thirty men. Some had been injured during the takeover, but others sought his help for long-standing problems. As Richard Clark explained, “We had sick prisoners who had never received any medical attention in Attica.” In need of more supplies, Hanson asked permission to send prisoner Tiny Swift out of D Yard to get medicine and splints. Swift had been sent to Attica on a life sentence for murder, but Hanson found him to be a dedicated caregiver in this stressful situation. Hanson was in fact so impressed with Swift’s dedication to patient care that when he returned with the supplies, the doctor decided to give him some additional on-the-spot medical training so that he could do more good once Hanson left.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

After taking care of the ambulatory patients, Dr. Hanson began making rounds, accompanied by a security detail of four or five prisoners. As they walked through the now dark yard, one of the men worked a bull- horn: “Anybody want a doctor? Anybody want a doctor?” Hanson grew somewhat fearful, especially when he noticed that the leaders were no longer keeping tabs on him. “It was dark, and people were guiding me around with flashlights, and all these menacing people were carrying clubs and weapons of all kinds.” But eventually he realized he had nothing to worry about. After also taking a trip through two tiers of D Block, where some of the elderly or infirm prisoners who might need care had chosen to sleep, Hanson was escorted out of the yard by the same man who had brought him in four hours earlier. He shook the doctor’s hand and thanked him “on behalf of his brothers.”

Around the same time that Dr. Hanson was leaving the prison, two top aides to Governor Rockefeller were coming in: General Buzz O’Hara, who earlier that day had facilitated getting water to the men in D Yard, and T. Norman Hurd, New York’s state budget director. Oswald briefed the governor’s men and took them on a tour of A Block, then invited them to a meeting with [Deputy Commission Walter] Dunbar, [Warden Vincent] Mancusi, and Major John Monahan and Chief Inspector John C. Miller from the NYSP. Everyone at the meeting was gratified to learn that Oswald, while still insisting on seeing negotiations through, was at least willing to discuss what would be required to retake the prison. Major Monahan felt that with five to six hundred troopers assembled outside, ready to move in as soon as they received the go-ahead, they now had everything they needed. General Buzz O’Hara disagreed; in his view, CS gas (a kind of tear gas) was essential for success in such an operation, and they had neither the gas nor the plane with which to disperse it over the prison yard. So O’Hara reached out to his contacts in the National Guard, who worked through the night to secure a CH-34 helicopter with an M-5 chemical dispenser and enough gas to incapacitate everyone in D Yard.

Back in D Yard, prisoners and hostages alike were still counting on successful talks. Both groups were grateful to have seen Hanson, but some felt fearful when he left. This was particularly true of the men over in the hostage circle. These men had been glad of the security afforded them so far, yet were worried about whether “the Muslims could really protect us.” On this score, hostage Don Almeter felt “more scared than I ever was in Vietnam,” and hostage John Stockholm was so scared that he could not even go to the bathroom when his captors gave him the chance to do so. As he recalled, his “body just shut down.” As the hours passed, though, these men began to feel much better about their prospects. In the middle of the night, a number of prisoners went into D Block’s cells and dragged out mattresses for the hostages to sleep on as well blankets to keep them covered.

The prisoners knew that the hostages were all that stood between them and what they believed would be a bloody assault on the prison. Despite the bravado they had displayed in their discussions with prison officials throughout the day, the men in D Yard were also terrified. They were not at all sure they could trust [lawyer Herman] Schwartz to get them an injunction against reprisals and they worried mightily about the sharpshooters that the NYSP had been placing on the cell block roofs above them. For this reason, as one prisoner explained, “most of us slept right out there in the yard.” At least out in the open they’d know if an attack was starting.

Despite the sense of foreboding, there were moments of levity and, for some, even a feeling of unexpected joy as men who hadn’t felt the fresh air of night for years reveled in this strange freedom. Out in the dark, music could be heard—“drums, a guitar, vibes, flute, sax, [that] the brothers were playing.” This was the lightest many of the men had felt since being processed into the maximum security facility. That night was in fact a deeply emotional time for all of them. Richard Clark watched in amazement as men embraced each other, and he saw one man break down into tears because it had been so long since he had been “allowed to get close to someone.” Carlos Roche watched as tears of elation ran down the withered face of his friend “Owl,” an old man who had been locked up for decades. “You know,” Owl said in wonderment, “I haven’t seen the stars in twenty-two years.” As Clark later described this first night of the rebellion, while there was much trepidation about what might occur next, the men in D Yard also felt wonderful, because “no matter what happened later on, they couldn’t take this night away from us.”

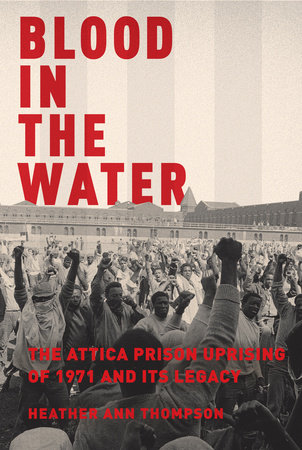

This is an excerpt from BLOOD IN THE WATER by Heather Ann Thompson. Copyright © 2016 by Heather Ann Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com