Opioids are remarkable.

For the treatment of severe acute pain, opioids can be the key to success. I was once administered opioid treatment, via intravenous injection, for 12 hours after undergoing major surgery. They took the pain away. I could get out of bed, move around and do respiratory therapy. I was out of the ICU in 24 hours. Opioids—briefly—were a key factor in my recovery.

But for some people, opioids are a little too remarkable. The well-being sensation from a pill prescribed after a surgical procedure can be life-changing. And some patients come back for more. As my mentor told me, prescribing opioid is like an airplane that is easy to take off the ground—but very difficult to land.

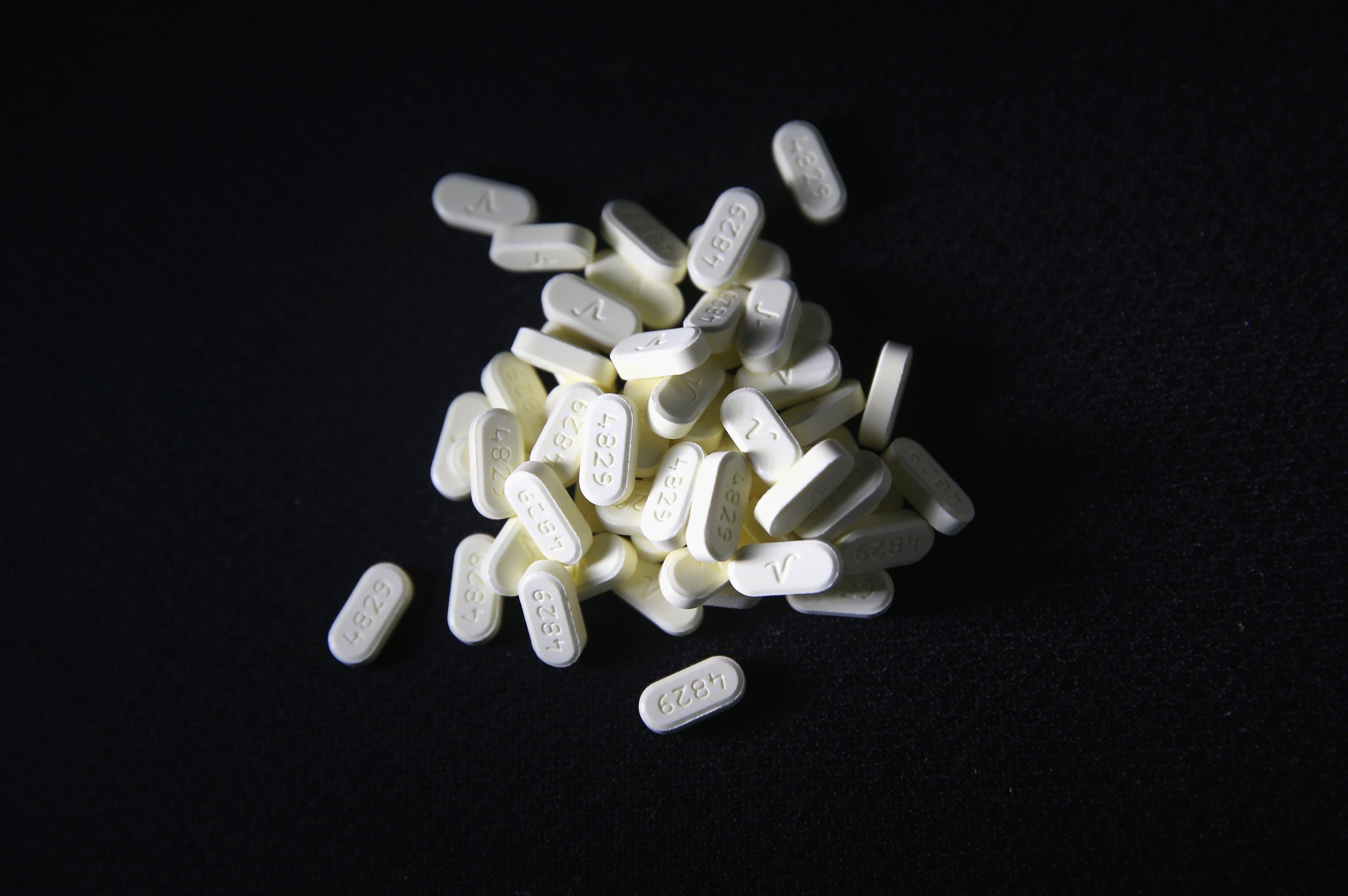

The problem is that too often, opioids are prescribed to treat chronic pain, a quick fix that can foster deadly addiction. Instead the goal of treatment for pain should be recovery of function, not complete resolution of pain.

In the U.S., prescription opioid sales have increased 300 percent since 1999—despite no substantial improvement in health and quality of life. Also increasing are overdose deaths. Nearly 30,000 people died from opioids in 2014, the highest on record. More than half involved a prescription opioid.

This crisis is a failure of our healthcare ecosystem and our quick-fix culture. We can all share the blame: physicians who feel anxious to meet patients’ expectations, pharma companies that oversell opioid benefits (and downplay the risks), insurers that fail to flag patients receiving high volumes of opioid prescriptions (and not properly reimbursing therapy) and patients who demand passive treatment.

While many are taking positive steps to reverse this trend, the problem will remain severe for years—unless we change a fundamental mindset among physicians, patients, payers and regulatory organizations.

Metrics—and Incentives—Drive Outcomes

In order to achieve significant change, we will need to make difficult, possibly unpopular, decisions. We must reconsider metrics and incentives.

The outcome metrics we share with our patients may not be productive. If we fail to reduce the amount of a patient’s back or leg pain, the patient and I can conclude that treatment was not helpful. But what if the patient can walk more and go back to work despite a moderate pain level? Can we call that success?

Think of the opposite scenario. What if we succeed in cutting the pain to a three on a one-to-ten scale—but that “cure” is misleading? Even if the pain is erased, the patient may not be active, still dependent and gradually loosing function from inactivity. Could opioids help in the short-term and harm in the long-term? Our crisis indicates that it may.

We also need to recognize the role incentives play in healthcare delivery. By incentivizing (or punishing) hospitals based on how patients subjectively rate a physician’s effort to control pain, we might unintentionally push providers to start or increase opioid medications.

And what about patients? Belief in a Magic Pill and a reluctance to exercise, lose weight or eat broccoli is their incentive. Additionally, out-of-pocket payments for physical therapy and counseling continue to be more expensive than medications.

So what is the incentive to seek active—rather than passive—treatment?

A (Not So) New Prescription for Pain Management

An old adage proclaims, Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional. Certainly, no one likes pain. And those who suffer chronic pain often endure levels of anguish that rob them of life’s many joys. But fighting chronic pain—and focusing exclusively on pain—can become a harmful exercise in futility.

But there’s a different approach to chronic pain care. The methodology is hardly revolutionary. You might even call it innovation-less.

In order to change outcomes, we all need to first change the metric of success. That means that in the initial stages of treatment, we become:

The final point will be the toughest. Despite knowing for decades that pain and behavior are intimately connected, mental health therapy remains taboo for many Americans—which is too bad, because chronic pain will not simply vanish through the surgeon’s scalpel and some magic pills. Managing pain sometimes requires pills and surgery, but it always takes hard work, and the patient must do his or her part.

The Beginning of a New Program

A well-structured long-term approach that caters to the right metrics and incentives will reap greater rewards than the quilt of exams and quick-fixes patients have come to expect.

And the old-school, innovation-less approach is about to be tested. On August 1, the Cleveland Clinic, where I work, launched a large-scale pilot program to treat more than 1,000 patients with chronic back and leg pain. All patients will undergo the same two treatments initially—physical therapy and counseling. And our key metric will be the restoration of function.

Patients will not be denied surgery, procedures or pain medication if the diagnosis calls for them. But those won’t be our starting point. We will also change the metric for assessing the efficacy of these treatment modalities. Rather than utilizing procedures as the “treatment of last resort,” they will be used as a means to an end. That is, the goal will be to help patients go through physical (and mental) rehabilitation so they can do the activities they used to take for granted: move, care for themselves, work and care for their loved ones.

Ultimately, this methodology should serve to lessen the community’s reliance on opioids and improve the utilization—and timing—of invasive procedures. If it works, the clinic plans to extend this approach to the treatment of other chronic illnesses.

Innovative? Hardly. The right course of action? I am convinced that it is. We’ll soon see.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com