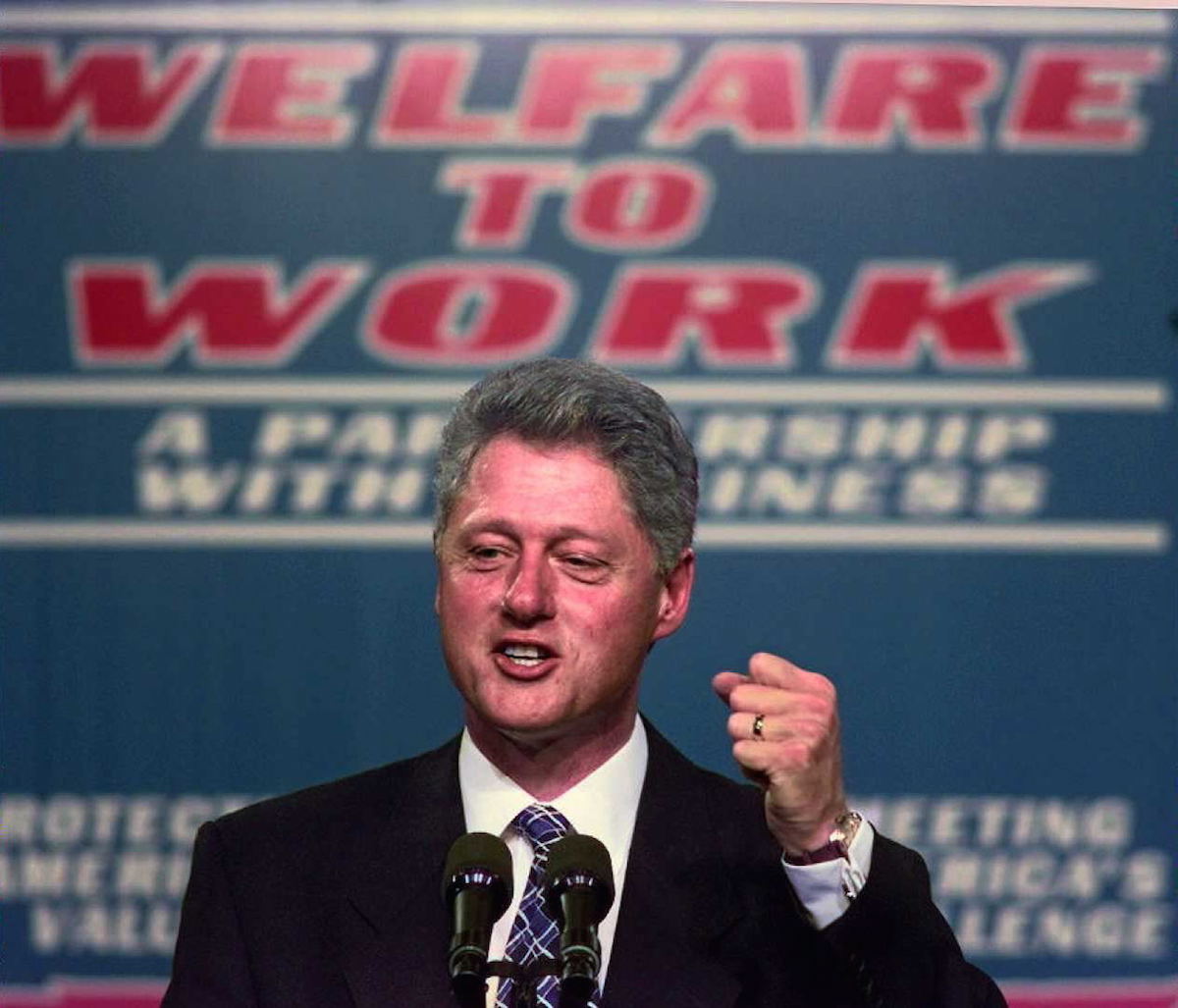

During President Bill Clinton’s first term in office, much of the United States took for granted that there would be welfare reform of some sort. The question was what it would look like. The answer came 20 years ago, on Aug. 22, 1996, when Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

President Clinton had promised as much during his first run for the White House in 1992, coming out of a recession that had led to a 33% increase, between 1989 and 1994, in the number of households receiving Aid to Families with Dependent Children. A TIME/CNN survey in 1994 found that 81% of respondents wanted “fundamental reform” to the welfare system, and a slightly higher percentage believed that the system already in place discouraged needy people from finding work.

Several proposals emerged out of the discussion. The most out-there plan, known as Talent-Faircloth, included a stipulation to deny any benefits to women who had children out of wedlock before the age of 21, sending that money to orphanages instead. The others varied but the ones in play were largely focused on making sure that people couldn’t make an active choice to be on welfare rather than working. Meanwhile, many on the left hoped that change would come in the form of more support for families, not a system that they saw as, in the words of Barbara Ehrenreich, “an implicit attack on the dignity and personhood of every woman, black or white, poor or posh” for the way it played on the stereotype of the welfare mother.

By 1996, however, especially after the midterm election of 1994 moved the federal government to the right, with the next presidential election approaching and and two vetoes of previous Republican-crafted welfare bills under his belt, Clinton seems to have been out of options. He himself was said to have remarked that it was “a decent welfare bill wrapped in a sack of s–t,” but, as TIME reported, he signed:

Historic turning points in social policy are not always obvious when they occur. Certainly Franklin D. Roosevelt did not foresee that some provisions of the Social Security Act he signed in 1935 would burgeon over the next 61 years into a mammoth federally financed and regulated welfare program. Last week, though, the equally historic nature of the decision facing Bill Clinton was clear not just to the White House but the whole nation. So the President turned his deliberations over a radical overhaul of F.D.R.’s welfare system into a solemn little drama.

Or perhaps a bit of “Kabuki theater,” as an official speculated, in which the actors played out stylized roles to a foregone conclusion. Several of the top 15 advisers who sat down with Clinton in the White House Cabinet Room for a supposedly decisive session Wednesday suspected the President had already made up his mind to sign the welfare-reform bill Congress was about to pass. A tip-off: Hillary Rodham Clinton was conveniently out of town at the Olympics in Atlanta and, White House watchers believe, already knew what her husband would do. If the First Lady had been in any real doubt about what her husband would do, Clinton watchers reasoned, Williams would have sat in to listen and report. Also, though no other participants knew it, senior policy adviser Bruce Reed had prepared only one advance draft of the speech Clinton would give, and it assumed a decision to sign (though Reed says he could have quickly revised it to defend a veto).

In retrospect, it seems inevitable that Clinton would sign. And not just to take away from Bob Dole one of the few issues the Republican contender had been counting on to gain traction in the campaign. Political strategists figured a veto might cost the President about five points in the polls, but Clinton could endure that with plenty to spare. A veto, however, would have repudiated the entire moderate, New Democrat stance—champion of family values, balanced budgets, more cops on the streets—that Clinton had been cultivating so assiduously since the rout of the Democrats in the 1994 elections. And, of course, there was that matter of his 1992 pledge to “end welfare as we know it.”

Moreover, Congress had stripped out of its new welfare bill many of the harsh provisions that had provoked the President to veto two earlier versions. The decisive breakthrough began in early June, when two obscure G.O.P. Congressmen—John Ensign, a freshman from Las Vegas, and Dave Camp, a third termer from Michigan—conferred after a meeting of Republican members of the House Ways and Means Committee. Says Ensign: “We both looked at each other and said, ‘This is crazy!’ ” What was crazy, they thought, was a decision of the G.O.P. congressional leadership to keep welfare reform combined in a single bill with drastic changes in Medicaid. That bill would be guaranteed to draw a third Clinton veto.

Ensign and Camp, however, wanted some real, popular legislation to present to their constituents. They got 52 House colleagues to sign a letter to Speaker Newt Gingrich and Senate majority leader Trent Lott urging that welfare reform and Medicaid be decoupled. Gingrich refused, but meanwhile Ensign was getting calls—30 in a few days, he says—from lawmakers who wanted to join his group. He and Camp got more than 100 House G.O.P. signatures on a second letter, and on July 11 the G.O.P. leadership gave in.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

As TIME explained, that bill limited welfare to five years, required recipients to work, required unwed teenage mothers to live with their parents, and much more. Today that bill is seen by some as a failure and by some as a success.

At least one potential problem with it was immediately clear. Even though the national welfare reform bill wasn’t signed until August of 1996, a pilot program in Wisconsin had gone into effect the year before. And while the 1996 bill was still new, it had already exposed a serious problem with the way so-called “workfare” was being implemented: if a state required mothers to work in order to receive benefits but did not adequately increase daycare options to match, children could be put at risk. Soon, those consequences were felt across the country: in 2000, in Tennessee, three babies died when they were left in vans by daycare workers at underfunded, under-regulated and overburdened daycare centers.

A 2002 study found that the effects of the 1996 law were that while “toddlers in day-care centers cognitively outpaced their peers in home settings by three months or more” and “mothers’ earnings rose modestly,” as TIME explained it, “many still lived in roach-infested housing, had to skimp on food and spent fewer hours singing and telling stories to their children.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com