Douglas Fairbanks knows what ails you. Greedy? Slothful? Vengeful? Overweight? Grumpy? You must do one thing: laugh. Laugh and you’ll be happy, fit, successful, a joy for your family and friends. Laugh and you’ll be rich. Laugh and you’ll learn, quite simply, how to live.

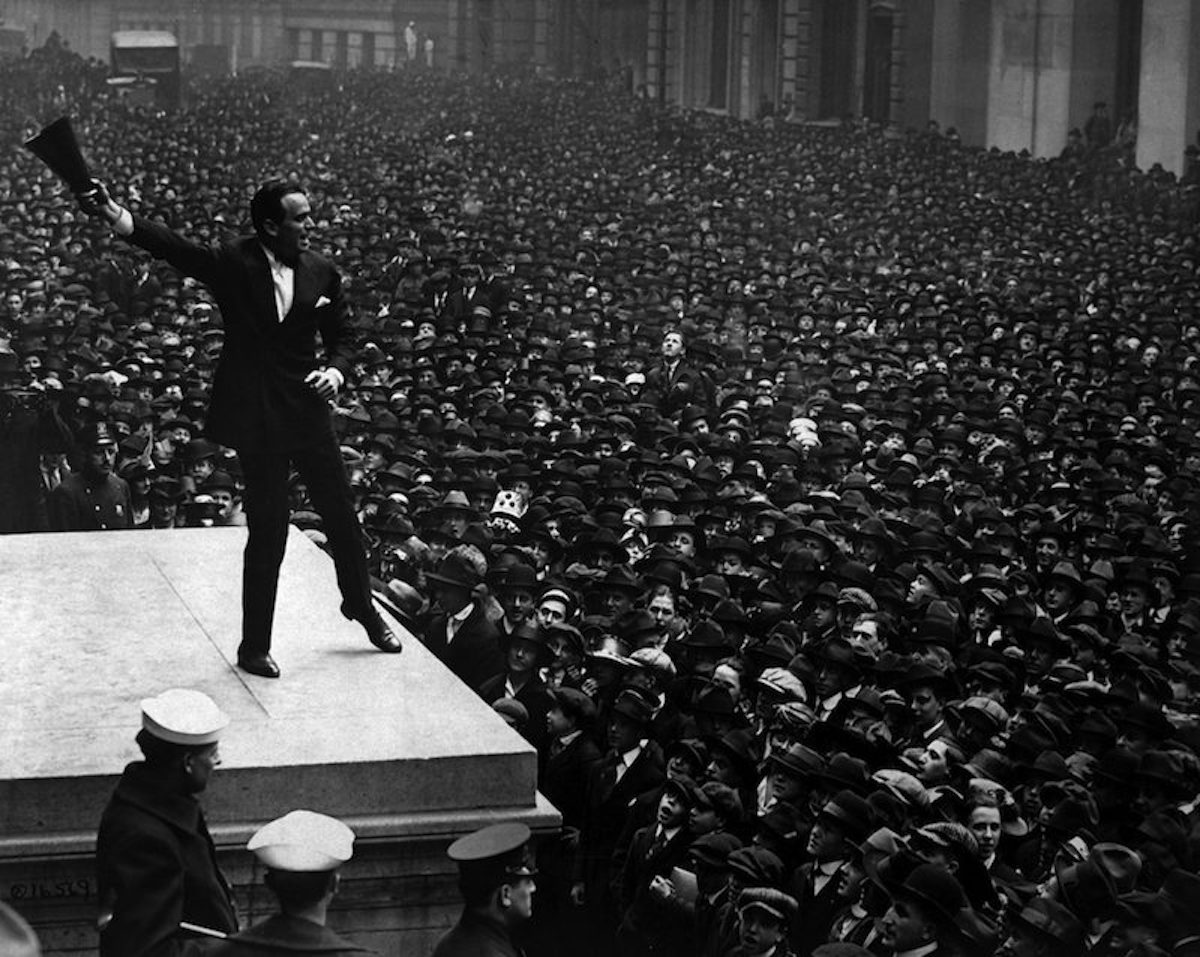

Or at least that’s the idea behind the silent film star’s self-help book Laugh and Live, published in 1917. Fairbanks was a multi-hyphenate heartthrob—he played Robin Hood and Zorro and was, along with wife Mary Pickford, one-half of the original A-list power couple; more recently, he inspired for Jean Dujardin’s turn in the Oscar-winning The Artist—but what he really wanted was to engage in a kind of public service.

The self-help genre wasn’t brand-new at the time, but Fairbanks was still an early adopter. Fifty years earlier, Samuel Smiles’ Self-Help was a bestseller, but the world of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People and Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking remained a solid generation away.

In his cheerfully persistent book, the subtext is: Lighten up, folks. This kind of all-purpose advice was a hallmark of early self-help books, which catered strictly to the everyman.

But as life got complicated, self-help did too.

It turns out that when you drown the Everyman with generalized advice, he’ll come up for air asking for more. “A market that is saturated turns to differentiation, to niche marketing, to open up new audiences, and self-help literature is no exception,” says Micki McGee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Fordham University and author of Self-Help, Inc: Makeover Culture in American Life.

Now topics that only warranted a slim chapter in Fairbanks’ book can take up an entire shelf at the bookstore. In fact, his book foreshadows many of today’s releases. “Exalted ego is an indication of degeneracy and may have been inherited,” a line from Fairbanks’ book, would fit right in with Ryan Holiday’s Ego Is the Enemy. Foreshadowing Tim Ferriss’ outsourcing tome The 4-Hour Workweek by 90 years, Fairbanks wrote, “The bigger the man, the less he encumbers himself with matters which can be delegated to others. His desk is clear of all litter and minutia—likewise his mind.” Even Arianna Huffington’s The Sleep Revolution can find its roots buried in his book: “When it’s all said and done and the exercise game has become a feature of his day’s work, he must settle down to good plain food and plenty of sleep.”

An over-saturated self-help market led to the rise in personal finance, fitness and relationship books. Authors tell readers how to live more spiritually or better manage their time, or both, somehow, at once. And that’s not to mention advice from celebrities, which is its own niche.

But splintering the market to death also has an upside: that many more people are being “helped.” One-size-fits-all American self-help books of the early 1900s didn’t concern themselves with women (or at least not women who wanted help with more than cleaning and dieting) or with concerns that might apply specifically to people of different ages, races and backgrounds. They spoke to the working white man—which meant they were often useless to others.

“Advice literature tailored to different groups, based on gender, age, sub-groups or professional status can provide more useful advice as it addresses the varied social expectations we each face in a highly differentiated social world,” says McGee.

Yet that fact only partly explains the boom — and shift — in the genre.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

“Self-help books completely respond to the time that they were written and they tend to prey on people’s fears and anxieties about that time,” says author Jessica Lamb-Shapiro, who sifted through hundreds of self-help books to write her experiential memoir Promise Land: My Journey Through America’s Self-Help Culture.

In 1917, Fairbanks was riding high on his film fame and so he preached what he knew best: joy and positive thinking. When the Great Depression hit a dozen years later, readers turned to authors advising on money matters and how to be frugal or get rich. Dale Carnegie’s first success hit at the tail end of the Depression, promising people an escape from their own mental ruts and advice on how to be a better salesman. In recent years, as workplace agita grows so, too, do the number of books to fix it.

“Generally an economic downturn or crisis leads to a jump up in books on personal finance and how to stay afloat,” says McGee, “but also to an increase in a counter literature that emphasizes spiritual rather than material values.” Case in point: the rise of Marie Kondo. “The plethora of contemporary decluttering books could, of course, only have emerged in a consumer society where we have more material goods than in any other time in history,” says McGee.

So where can the genre go next?

“There’s sort of a ‘classy self-help book’ genre emerging,” notes Lamb-Shapiro, pointing to research-based hybrid self-help books (like Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit or anything Gladwellian) that act as antidotes to traditional self-help’s fuzziness.

Or there could be another completely new shift on the horizon. McGee points to the success of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, which eschewed the ideology of individualism for progressive values, as one sign the culture might move away from individual makeover solutions in favor of advice on how to build up communities instead. “A self-help book that would animate the movement for economic and social justice and infuse it with aspiration and optimism would be a book that would change the conversation in ways we can’t even begin to imagine,” she says.

But perhaps each generation gets the self-help it deserves. There’s a deep irony that Fairbanks told the world that laughing is the key to living, when his film audiences couldn’t actually hear a single thing that he said. But then, a decade after writing his relentlessly optimistic book, the advent of the talkies sunk Fairbanks’ career—proving, at least briefly, that there are some things laughter can’t fix.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com