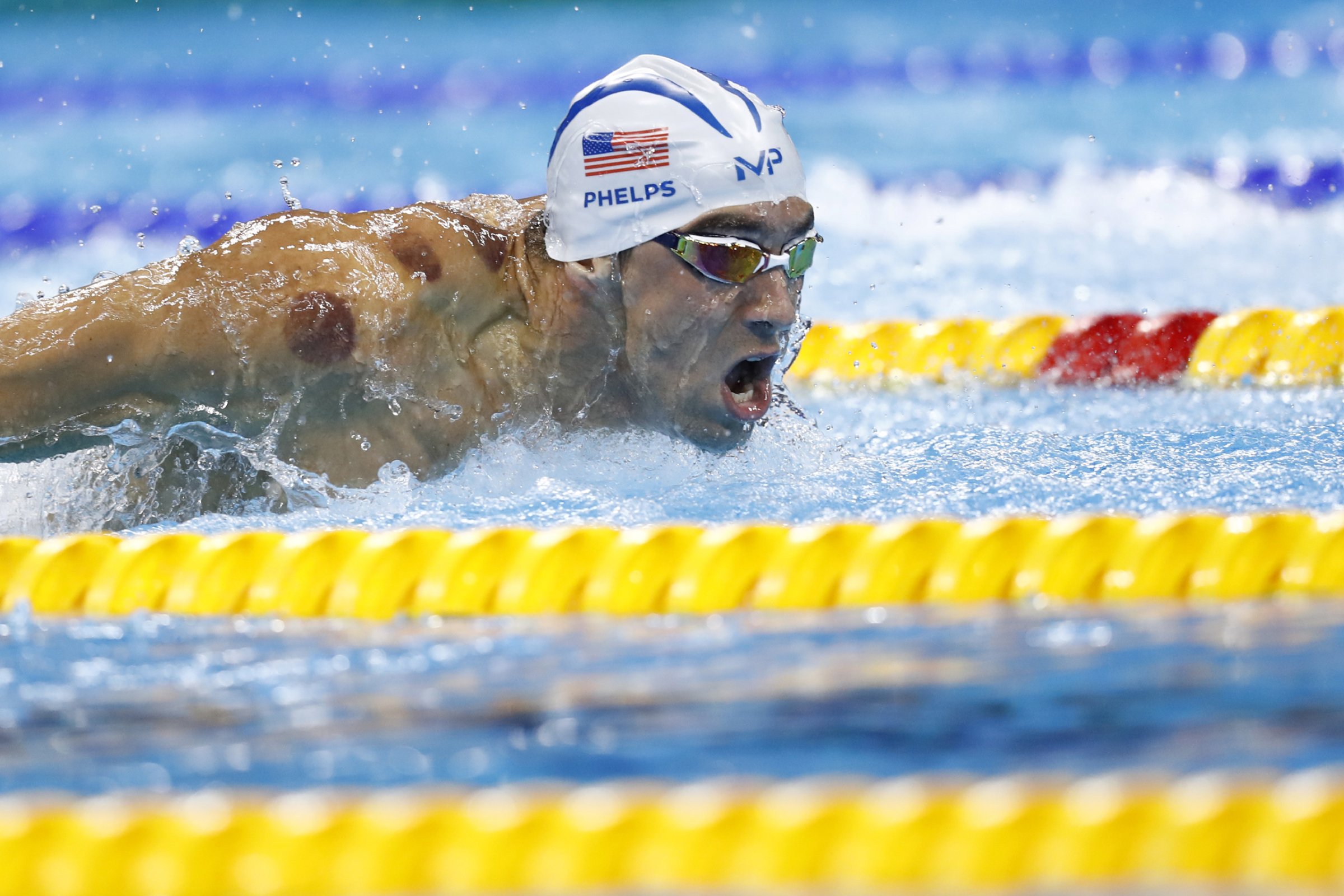

They were hard to miss — the dark, purply circles dotting Michael Phelps‘ back and shoulders and running all the way down his leg. Perfectly circular, they look like some kind of rash.

In Phelps’ case, they’re completely intentional. “I’ve done cupping for a while before meets,” says Phelps. “But I haven’t had a bruise like this for a while. I asked for a little help yesterday because I was a little sore and I was training hard.”

Cupping is a Chinese practice of sucking the skin away from the underlying muscles for a short period of time in order to stimulate blood flow. For swimmers, you’d want to do that to promote faster recovery and to swish away the build up of any lactic acid in the muscles that can lead to soreness, not a good thing if you’re racing heats in the morning and finals in the evening of the same day and have more than one race over a week.

Traditionally, cupping involves wiping the skin with something flammable like alcohol, and then lighting a match in an inverted small cup to build up heat. The match goes out, and the cup is placed over the skin, where the heat builds up pressure and starts pulling the skin away. Over several minutes, the blood vessels start to expand and tiny capillaries near the surface break, which causes the redness.

The U.S. swimmers, including silver-medal winner Chase Kalisz and bronze medalist Dana Vollmer, have also adopted the practice in <a href="http://

Some doctors say there isn’t enough evidence that cupping therapy works, but as TIME reported earlier, it has been thoroughly studied by some researchers: “A 2010 review of 550 clinical studies … concluded that the ‘majority of studies show potential benefit on pain conditions, herpes zoster and other diseases.’ None of the studies reported serious bad health outcomes from the practice.”

Keenan Robinson, Phelps’ longtime strength-and-conditioning coach, says he first introduced him to cupping in 2014, just before the pan-Pacific championships. The previous year, Phelps’ coach Bob Bowman held a training camp at altitude, and several Chinese swimmers attended. They brought with them their physical therapists and their own recovery methods, which included cupping (they did it the semi-old-fashioned way with bamboo shoots, alcohol and lighters).

In 2015, Phelps started increasing his workouts and the intensity of his swimming to prepare for Rio, and finding a quick way to recover and relax his muscles was a high priority. “I wouldn’t say he was on it right away,” says Robinson. “When he realized it would take five minutes and that this could get him from Tuesday to Thursday [workouts] and from Thursday to Saturday [workouts], he was on board.”

Robinson says he doesn’t use cupping to heal, per se, but rather to help keep the fascia — which are knitted in between and on the surface of muscle — lubricated. That allows muscles can move more freely and easily.

“The intent is to minimize fascial restriction so the motion is more smooth,” says Kevin Rindal, who works with USA Swimming. Instead of pushing down on muscle and fascia, as massage does, cupping pulls the layers of muscle and fascia apart, much like separating the layers of a flaky pastry, so fluid can flow more easily in between them to keep them well-oiled.

“We know some clinical studies say it does cause great change in cellular activity, and muscle activity, and fascial activity, so we’ll apply it to athletes well in advance of even before they go to Olympic trials,” says Robinson. “[We wouldn’t] start trying it on them at the Olympics. We want them to get exposure and say, Well, you’re telling me this does this but I don’t feel it so let’s move on to the next modality. We’re trying to use whatever we can to help them really move better.”

For Phelps, that’s getting cupped around twice a week. Even if it does leave a mark.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com