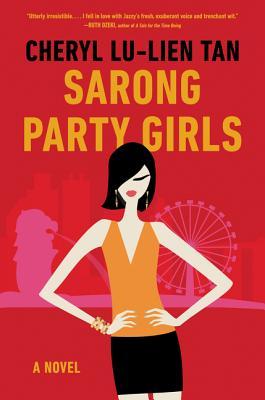

Tan is the author, most recently, of Sarong Party Girls

My father had just one question when he started reading my first novel earlier this year: “Who taught you to speak like that?”

Written in Singlish—the folksy patois of Singapore that combines English, Mandarin, Malay and Chinese dialects including Teochew and Hokkien—Sarong Party Girls has a narrative voice that’s a little unusual, certainly in the United States. At its best, the Singlish I grew up speaking with my friends and hearing in the colorful hawker centers and wet markets of Singapore is direct, often playfully vulgar, witty and self-deprecating. In short, it reflects rather well the spirit of my people.

As a Singaporean who’s lived in the U.S. for more than 20 years now, I’ve long held Singlish dear to my heart. People in the West often imagine Singaporeans as boring government stooges who love nothing more than to adhere to the endless rules my country has regulating everything from flushing the toilet to what fruit you can’t carry on public transportation. But listen to any Singaporean erupt in Singlish, and you’ll know that isn’t true at all.

When I hear myself speaking it, I feel as if I’m slipping into a different skin—my true Singaporean one. And this is why my father’s question perplexed me. I didn’t have to be taught Singlish—it’s always been around me, on the streets and in shopping malls, as well as in my aunties’ kitchens. Doesn’t Singlish as an informal dialect rather directly reflect who we are as a people?

In Singlish, “Why are you behaving in this way?” is transformed into a guttural “Why you so like that?”—best accompanied by a defiant tilt of the chin. To “catch no ball” means to not understand—the Singlish phrase is the literal English translation of the Hokkien term for being perplexed, “liak bo kiu.” If someone tells you to “Gostan!” while driving, you’re being told to reverse—it comes by way of Malay slang derived from the English nautical term, “go astern.” The word “lah” is attached to just about every other sentence as a form of emphasis—similar in a way to how some Americans use “man.”

As much as I take pleasure in Singlish and miss it when I’m far from Singapore, my father has never been a huge speaker of it. “Have you ever heard me speak Singlish to you?” my father asked at the dinner table in Singapore a few days after I’d proudly given him an advance copy of Sarong Party Girls. “I don’t even use the word ‘Lah.’”

My father’s dismay at my novel was understandable. He was 20 when Singapore gained independence in 1965; he was among the euphoric and newly galvanized Singaporeans at the time who believed in the collective goal of fashioning our tiny, still relatively sleepy Southeast Asian island into a dynamic world-class economy. His was a generation encouraged to shed not just Singlish in favor of standard or Queen’s English, but also native Chinese dialects such as Cantonese, Teochew and Hakka in favor of Mandarin.

At home, we spoke mostly English—the sad reason that my Mandarin is so-so, and I can barely speak Teochew and Hokkien, the Chinese dialects of my grandmothers. My father—who so wanted me to grow up to be a barrister that he gave me a dictionary of legal terms when I was 6—knew that if I were to ever don those silks, I needed to speak perfectly.

His desires and ambitions for me—and his wariness of Singlish—run parallel to the Singapore government’s. Despite its color, verve and efficiency, Singlish is a patois that has been under fire for years in my native country. The government of Singapore, a relatively young city-state that has placed great emphasis on having its citizens be competitive in the global economic arena, has long urged us all to focus on being fluent in proper English and not speak Singlish. In 1999, Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of modern Singapore, denounced Singlish as “a handicap we must not wish on Singaporeans.”

When then-prime minister Goh Chok Tong launched the “Speak Good English Movement” the next year, he dismissed Singlish as “English corrupted by Singaporeans.” In his National Day speech that year, he even devoted a segment to discussing Phua Chu Kang, a popular Singaporean sitcom featuring the escapades of an endearing, uneducated contractor who frequently spewed Singlish terms like, “Don’t play play!” (Meaning: You should take this seriously!) Mr. Goh noted his concern over Phua Chu Kang’s popularity and suggested that the character used too much Singlish, joking that perhaps he could take an English class. His comments were duly noted—the Singlish was toned down in future episodes of the sitcom.

In recent months, however, the topic of Singlish has been bubbling up far from Singapore’s shores. This spring, the Oxford English Dictionary announced that it was adding 19 Singlish words to its lexicon, including “ang moh” (Caucasian), “shiok” (delicious or great) and “lepak” (to relax). The New York Times ran an opinion piece in May exploring the Singlish phenomenon, prompting a letter in response from the press secretary to our prime minister Lee Hsien Loong, defending the government’s stance against Singlish: “Using Singlish will make it harder for Singaporeans to learn and use standard English.”

As much as I understand the government’s need to defend its campaign and English goals, I have to ask: can’t you trust us to be able to speak both?

Most Singaporeans I know are already adept at speaking a number of different languages—English with at least a little Malay, Mandarin, and the vulgar words in Hokkien for good effect, seem de rigueur for Chinese-Singaporeans, for example. Conversely, my Singaporean friends of Malay and Indian descent often know English, of course, and a little Mandarin and Hokkien as well. And from what I can see, we are a nation adept at code-switching—we know that the way we speak to our friends or bus drivers (yes, often in Singlish) has to be different from how we present ourselves in the boardroom or at school. To actively urge us to give up a language that speaks to the very heart of who we are, that so beautifully represents the melting pot of Chinese, Indians, Malays and Eurasians that we are, is shortsighted, surely.

That’s why I chose to write my novel entirely in Singlish. While some may see this as a small act of political defiance, I see it merely as showing my people and our lives sans the lens of “proper” English.

Fortunately, perhaps, governments and novelists do not have to have the same priorities. Governments, especially the governments of small nations without an imposing cultural history, tend to want to present their citizens in their Sunday best, but the world of the novelist, at least the novelist who aspires to represent the world as it is, is the work-a-day world, the world in which Sunday comes, at the very most, but once a week.

It’s impossible to imagine Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in the language of the White House, for example. And nor would one want to wade through White House reports written in the fractious language of the Beats.

Singlish is no different, and to celebrate Singlish is to celebrate an existing world, that of modern Singapore—to celebrate the extraordinary and unique vitality of our small city state.

And this is a point that my father has come around to—to some degree, after getting amused and a little fired up after seeing the recent continued reignited controversy over Singlish. In fact, this actually inspired a little Singlish note from him that referenced the Malay word “pengsan,” which means to faint or fainting. “Better still if the (People’s Action Party—PAP) government starts attacking the Singlish style,” Dad said. “Then you have national controversy and sales go even higher until PAP becomes Pengsan And Pengsan.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com