It’s hard to overlook a beast that measures 24 feet long and weighs more than 16,000 lbs. (7.3 m and 7,250 kg). It’s harder still to ignore a whole species of them. But that’s what scientists had effectively done for, well, as long as the animal has lived on Earth, which could mean for 50 million years.

The species—a long-rumored type of beaked whale—is at last getting the recognition it deserves. And along with the new respect comes a new, if not yet official, name: karasu, or Japanese for “raven.”

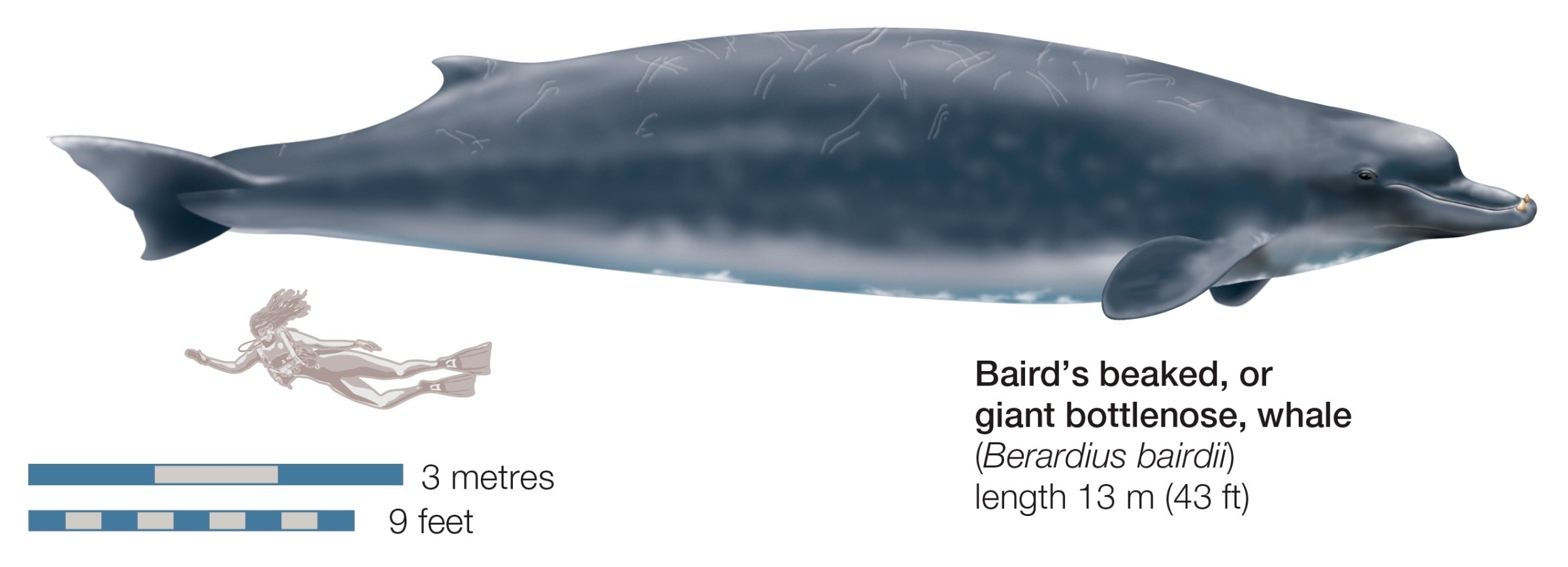

The karasu has been speculated about for more than 70 years, after Japanese whalers first reported fleeting sightings of a type of beaked whale that looked a lot like a Baird’s whale, only smaller and darker. Baird’s whales usually measure up to 39 ft. and weigh up to 24,000 lbs (12 m and 10,900 kg). They are also lighter in color—more of a slate-gray than a near-black.

The new whale—if it existed at all—showed itself only rarely. It was reportedly seen exclusively in the Nemuro Strait, at the northeast corner of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost large island. And it was seen only in the spring. Its dark color and its floppy dorsal fin made it hard to pick out against the water before it vanished again. The sightings, however, were frequent enough that the dark, swift animal earned its raven nickname.

Chatter about the karasu resurfaced in June of 2014, when a dead whale washed up on the shore of St. George Island in the Bering Sea near Alaska. It looked like a Baird’s, but it was too small and too pale, and its aged, discolored teeth suggested it could not be a juvenile. It had to be a whale that was full-grown for its species—whatever that species was.

Serendipitously, the remains were spotted by a local biology teacher, who knew enough to call in other experts, who knew enough, in turn, to pass the carcass onto the branch of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in California. There it came into the custody of molecular geneticist Phillip Morin, who decided to get to the bottom of the mystery.

As Morin and his team of 15 co-authors describe in a paper published in the journal Marine Mammal Science, the work they did was painstaking. They began with DNA samples from the newly discovered carcass and compared them to samples from 178 other whales that were thought to be related. Some of the material had been taken from live whales, some from dead, beached whales, some from whale flesh sold in Japanese markets. Some too was taken from museum specimens of preserved bones and bone powder.

What the scientists were looking for with all this evidence was a way to distinguish the possible karasu not just from the ordinary Baird’s, but from another similar species, the Arnoux’s beaked whale. Just proving that the new find was not a Baird’s did not have to mean it represented a species to itself; it may just have been an oddball Arnaux’s.

But it wasn’t. Morin’s work found a fairly close relationship between the new specimen and Arnoux’s, but not close enough for them to be part of the same species. And the beached whale was even more genetically distant from its supposedly closer kin, the Baird’s. The sea raven that the Japanese whalers thought they’d seen was the real deal.

“It’s just so exciting to think that in 2016 we’re still discovering things in our world—even mammals that are more than 20 feet long,” Morin told National Geographic.

Now that the karasu—official name pending—has been proven, Morin and his colleagues are working to determine more about where and how it lives. The fact that it is rarely seen by whalers in the north suggests that it spends most of its time in warmer, more southerly waters. And the scars the carcass bore of what appears to be a shark bite—also more likely to have been incurred in the south—seem to confirm that.

No matter how the karasu lives, the death of this one member of the species is one more bit of proof that the sea has not yet given up all of its secrets. Even 3.5 billion years after life on Earth first emerged, it continues to surprise us.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com