In the summer of 1982, while he was still opposition leader in Bonn, future German chancellor Helmut Kohl expressed his concerns about the plans for a national Holocaust museum in the United States. Peter Petersen, a CDU member of the Bundestag, recorded what Kohl had said to a group of Bundestag parliamentarians about the museum, which “the Jews,” as Petersen put it, were building in Washington. In the early 1980s, he summarized Kohl’s statement: “What would a young German visiting the United States think when he passed the Holocaust Museum on the Mall? . . . What would he feel when he saw his country’s entire history reduced to these twelve terrible years? Was this the way in which the United States was going to treat its most valued European ally?”

Throughout the 1980s and the early 1990s, a network of mostly conservative West German officials and their associates in private organizations and foundations, with Kohl located at its center, perceived themselves as the victims of the afterlife of the Holocaust in America. They were concerned that public manifestations of Holocaust memory—for example museums, monuments, and movies—could severely damage the Federal Republic’s reputation in the United States.

Of course, the Nazi past had affected the image of the Federal Republic abroad since its founding in 1949. But the 1980s were a unique time: as the Federal Republic came to see itself as a nation-state with its own positive traditions and history, it was a central goal of the Kohl government to escape Hitler’s shadow. At this historical juncture, however, representatives of the American Jewish community, including prominent Holocaust survivors like Elie Wiesel, were also in the process of transplanting the perspective of Holocaust victims into the popular, political and academic culture of Germany’s superpower ally, the United States.

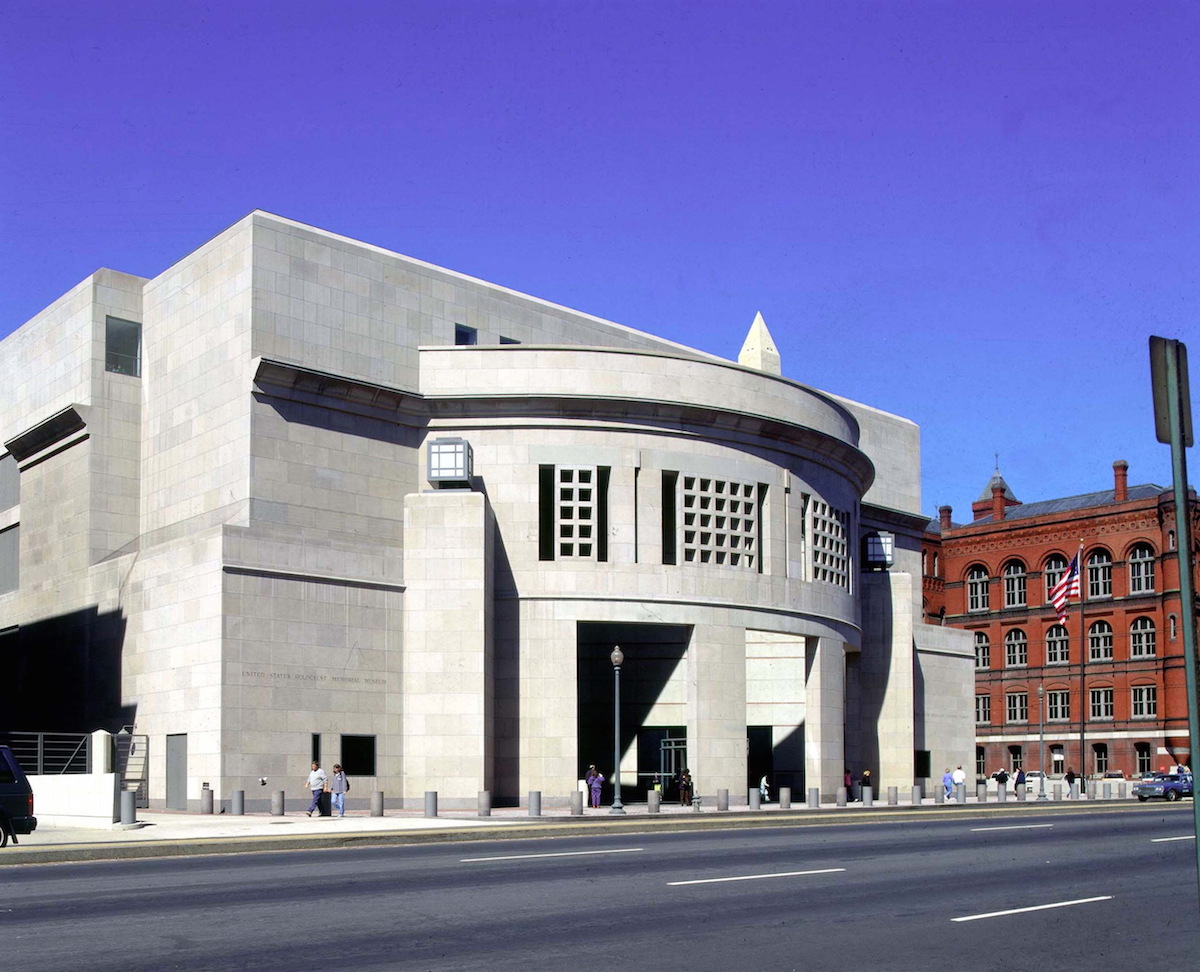

The Kohl government’s Holocaust angst culminated in the opposition to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). The museum, conceived in 1978 and completed in 1993, epitomizes what scholars like Alvin H. Rosenfeld have called the Americanization of the Holocaust. While there had been little continuous public engagement with the mass murder of European Jews outside of Jewish communities in the postwar decades, the discourse changed significantly in the 1970s. The Holocaust became an American memory, a moral point of reference in a variety of contexts. It still provides universal lessons for diverse groups, causes and beliefs.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

From the beginning, Kohl’s government exhibited a highly skeptical attitude toward the establishment of a museum that would permanently anchor Holocaust memory in American life. The leadership around Kohl considered the USHMM a state-sanctioned reduction of German history to the Holocaust and, as the German ambassador in Washington Peter Hermes stated it in the early 1980s, an “anti-German museum.” They assumed that it would portray Jews as victims, Americans as liberators—and Germans only as mass murderers. Such a narrative not only collided with the Kohl government’s domestic politics of history in the 1980s, with its emphasis on German wartime suffering and resistance to Nazism, but it also seemed to pose a threat to the country’s reputation abroad. Hence, Kohl’s government set out to influence the content of the museum’s permanent exhibition.

Through a series of behind-the-scenes interventions, a network of official and unofficial German emissaries attempted to integrate the history of German anti-Nazi resistance and of postwar West Germany into the exhibition concept. They aimed to show that not all Germans had been Nazis and that the Federal Republic had learned its lessons. For instance, they considered the country’s coping with the Nazi past, its model democracy and the alliance with Israel a success story, which should be told in the museum. For more than a decade, German intermediaries tried to convince the museum planners to design the exhibition accordingly, arguing that the museum would be incomplete without references to the “good Germans” that lived and suffered through the Third Reich as well as postwar West Germany’s accomplishments. As claimed in interviews and oral history transcripts with former museum representatives Michael Berenbaum, Miles Lerman, and William Lowenberg, they also offered a very large donation—up to $50 million—to make an even more convincing case in Washington.

West Germany’s Holocaust angst was not just a question of image and prestige, but of real foreign policy concerns. Kohl’s government assumed that visiting a Holocaust museum could cause Americans to question the alliance with the Federal Republic—the pillar of German security and prosperity during the Cold War. A key advisor to Kohl, Hubertus von Morr, summarized this sentiment: “We cannot understand why America wants its young people to go to that museum and come out saying, ‘My God, how can we be allies with that den of devils?’”

A specific form of “secondary” anti-Semitism complemented and catalyzed German Holocaust angst. This defense mechanism against feelings of shame or guilt for the Holocaust revealed itself in the assertions that American Jews could not “forgive” the Germans and that they exploited the suffering of Jews during the Third Reich for political and financial gain—an alleged conspiracy that Norman Finkelstein later controversially termed the “Holocaust industry.”

In the end, all German efforts to change the content of the USHMM failed.

Museum planners—many of them Holocaust survivors—considered German demands for a modification of exhibition either illegitimate or irrelevant. They also rejected those demands based on their personal experience of persecution and suffering under Nazism. However, museum planners never intended to create an anti-German institution, but to firmly anchor in American life what they believed to be universal lessons of the Holocaust.

The Kohl government realized at some point that all efforts to change the USHMM’s content were doomed, but they also acknowledged that American Holocaust memory was not an anti-German plot by American Jews. This learning process contributed to an indeed remarkable transformation: since the 1990s, Germany has completely reversed its position and fully acknowledged the Holocaust and its legacies. In fact, Kohl even stated in 1998, his last year as chancellor, that the memory of the Holocaust had become the “core” of Germany’s “self-concept as a nation.” The country’s leadership also realized that this memory did not necessarily have to weaken Germany’s international reputation, but rather that an open, unapologetic engagement bore the potential to strengthen it. In the course of the 1990s, the Holocaust therefore changed from a burden into a special responsibility.

Jacob S. Eder is a historian at the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, and the author of Holocaust Angst: The Federal Republic of Germany and American Holocaust Memory since the 1970s, from which this piece is adapted.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com