It’s 1911, and the world is buzzing with awe and innovation and change.

The first airplanes dot the skies, Marie Curie has just won her second Nobel Prize, George V is crowned King of the United Kingdom, the Titanic is unveiled as the world’s greatest ship and, in a Paris orphanage, there is a baby raffle.

That’s right, in an effort to raise money and find homes for orphaned children, a Paris foundling hospital held a raffle of live babies.

Most of what we know about this “Loterie de Bébés” comes from an article published in the January 1912 issue of Popular Mechanics, which covered the raffle as a news brief.

“The management of a foundling hospital held the raffle, with the consent of authorities, as a means of finding homes for a large number of its charges, and to raise money,” the article reads. “The proceeds of the raffle were divided among several charitable institutions. An investigation of the winners was made, of course, to determine their desirability as foster parents.”

Though an event like this would certainly be newsworthy, it’s worth considering the fact that the story was presented as a straightforward news brief and not a cautionary tale. Something like this wouldn’t necessarily have seemed that outlandish at the time, considering the way people treated children.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In 1911, the problem of abandoned children in urban areas was still Charles Dickens-level alarming. Child labor was practiced in many major cities across the world, and orphans were sometimes forced orphans to work with dangerous equipment in factories and on assembly lines under almost no supervision. And that was sometimes the best-case scenario. Children who didn’t make it to an orphanage were left to fend for themselves on the busy streets of bustling cities like Paris and London and New York. The street life often to led to a life of crime.

The kids who did make it into some early orphanages and children’s hospitals were only marginally better off. In fact, America’s first official venture in policing childcare practices wouldn’t come until a year later. In 1912, the United States Children’s Bureau was founded; this still-existing federal agency was organized to investigate infant mortality, birth-rate, orphanages, juvenile courts, desertion, child labor, diseases in children and more. The deinstitutionalization of orphanages and children’s hospitals didn’t start until the mid-20th century, when many countries began finding replacements for group orphanages and large children’s institutions. For example, in America, orphanages were generally replaced with a foster care system and private adoption agencies that advocate for specific children in need of adoptive parents—but that change took decades.

Foundling hospitals like the one in Paris were among the very best options when it came to dealing with orphans and other abandoned children. They were far from perfect, but they were still an important step in the lengthy evolution of childcare. It’s tough to celebrate an event with human beings as prizes, but also hard to deny the intentions of the orphanage.

So it’s not surprise that, more than a century ago, people may have considered the baby raffle a celebratory affair.

More importantly, unique stories like that of the Paris Baby Raffle would have helped to bring attention to a larger problem—and help millions of children in need in the process.

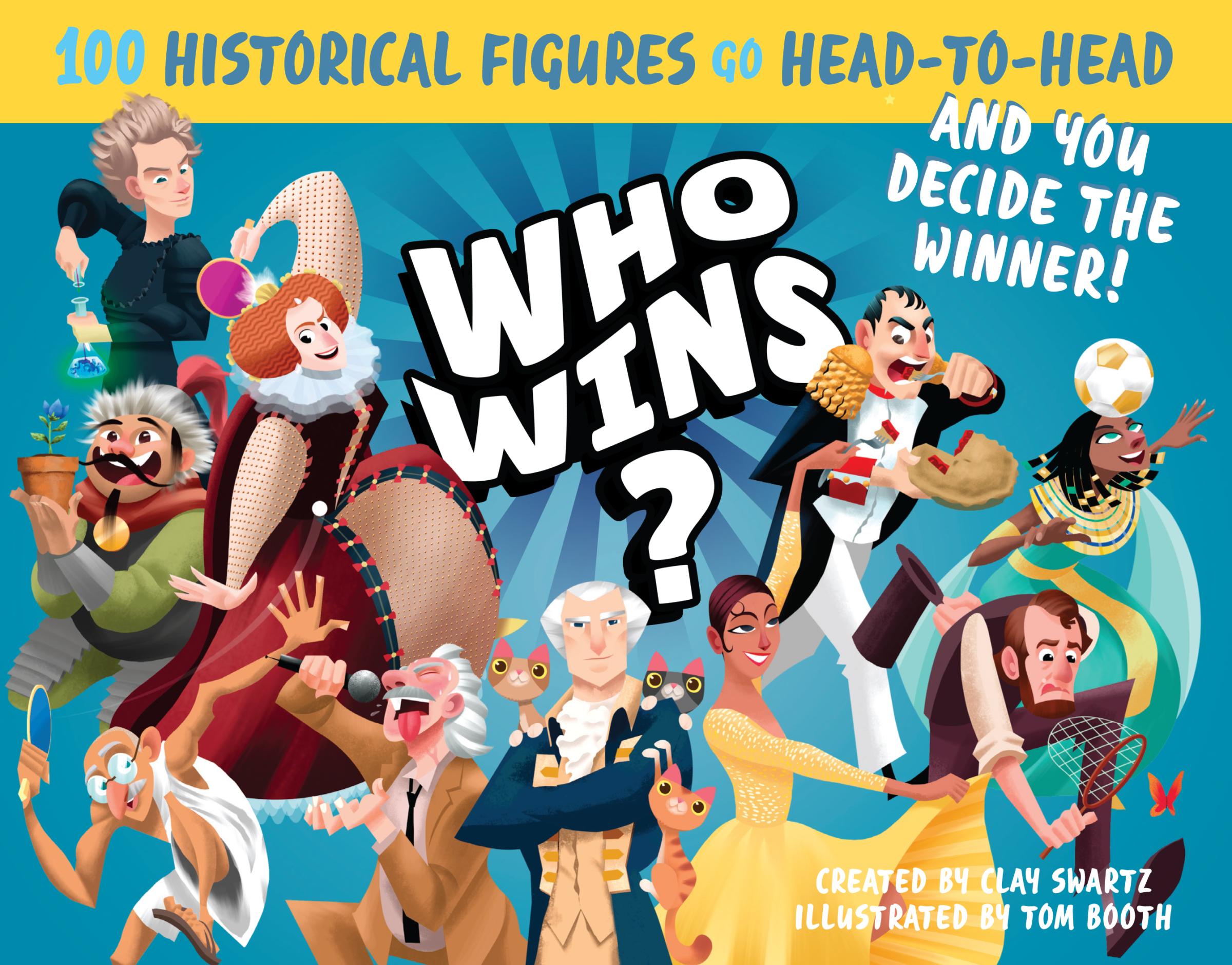

Clay Swartz is the author of Who Wins? 100 Historical Figures Go Head-To-Head and You Decide the Winner.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com