In the walk-up to the 2016 Summer Olympics, which officially open in Rio on Friday, many fear a Russian doping scandal and infrastructure gaps in the Brazilian city have threatened to overshadow the games. But at least concerned observers can take comfort in one fact: as long as the stadium has seats, and as long as a political leader doesn’t pay off the athletes so he can personally win a gold medal, chances are Rio won’t be as dramatic as the ancient Olympics were.

TIME asked archaeology experts and historians to talk about the most surprising aspects of the first games, which took place at Olympia in Greece every four years between 776 B.C. and 393 A.D.

Here’s what to know:

Why it started: While sports fans might figuratively worship certain athletes at the Rio Olympics, actual religious worship was a key part of the ancient games. The games, held at a sanctuary site for Zeus in Olympia, were part of a religious festival held in honor of the God.

“Those who competed competed to please a god or goddess or a hero,” says David Gilman Romano, the Karabots Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Arizona School of Anthropology (who spoke to TIME by phone from the Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project in Acadia, the site of a possible precursor to the Olympic games).

Why it stopped: Religious conflict led to the abolishment of the games in 393 A.D., by which point the Roman empire controlled the region. Emperor Theodosius, a Christian, considered them pagan.

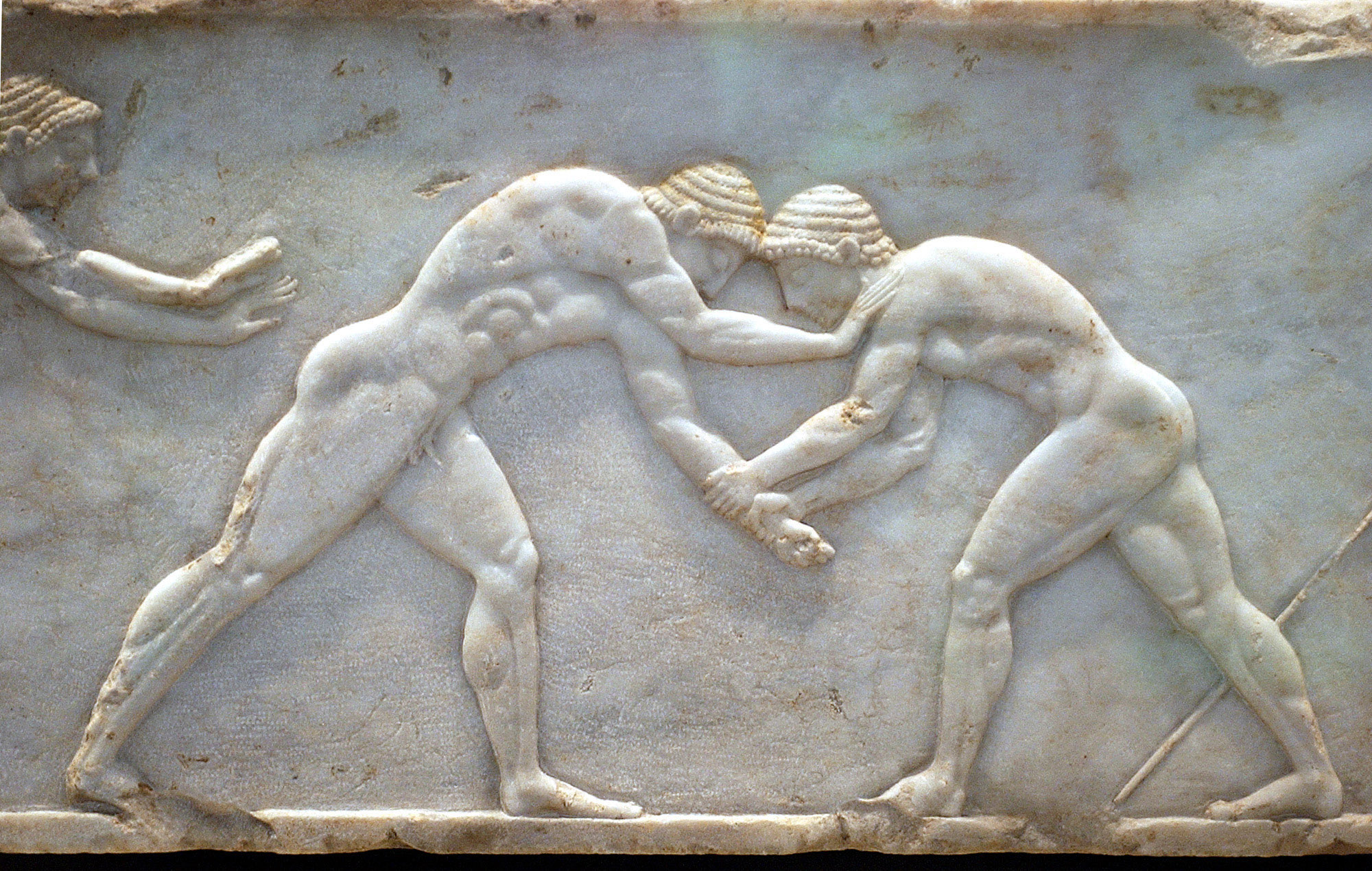

The sports: The 2016 Olympic athletes will compete in 42 different sports, but ancient Olympics started with only one, the stade race, in 776 B.C., for which athletes would just run the length of the stadium. Then came the diaulos, in which athletes would do that twice. A long distance race was later added, and eventually, javelin, discus and long jump, said to have been accompanied by flute music. There were equestrian events like chariot racing, wrestling and boxing, and a wrestling-boxing hybrid called pankration. While no eye-gauging or biting was allowed, strangulation was fair game in pankration, says Tony Perrottet, author of The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games.

Archaeological evidence reveals that athletes coated their bodies in olive oil. Romano suspects that practice was useful for the wrestling and pankration so it’s “less easy for someone to get a hold of your body” or to “protect skin while you’re rolling around in the sand.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The prizes: Victors received olive wreaths cut from a sacred grove and cash awards from their home city, says Romano. (Which is only fitting: “Athlete” is an ancient Greek word for “one who competes for a prize.”)

One important distinction between the modern and ancient Olympic, says Andrew F. Stewart, a professor of Ancient Mediterranean Art and Archaeology at the University of California-Berkeley, is that the ancient Greeks, while they kept track of who won, didn’t seem to have kept records like fastest time.

The memorable athletes: All male. Leonidas of Rhodes was arguably the best runner, winning 12 olive wreaths, while the official Olympics website recognizes Milon of Croton as a six-time wrestling champion. Astylos was another acclaimed runner who won the stade and diaulos race in three Olympiads. When he ran for the city of Croton in the first race, residents erected a statue to him. But when he ran for its rival city in Sicily, Syracuse, his statue in Croton was demolished.

Perhaps the most memorable of all wasn’t even an athlete: After Rome conquered Greece, Emperor Nero was desperate to become an Olympic victor. He “paid off everyone” so he wouldn’t have to actually compete against anyone and won six olive wreaths and events in the four-horse chariot race in 67 A.D., according to Romano.

The women: Married women were said to have been banned from watching the games. Legend has it that if any woman tried to sneak in, she’d be thrown off Mount Typaeon. There was, however, essentially an Olympics for unmarried girls at the same stadium in Olympia. A committee of 16 women organized it in honor of the goddess Hera, and the women competed in three age categories. Stewart believes the purpose of those games was “to make the girls stronger so they’d bear strong children.”

The fan experience: “It was like an extremely badly-planned rock concert, the Woodstock of antiquity,” according to Perrottet, who says to picture a stadium that held up to 45,000 spectators but had no seats. “There’s one hotel, no sanitation, people sleeping in tents, some al fresco,” he says, and a “dried-up river” where visitors may have relieved themselves.

Diseases would spread through the crowd, so “Zika wouldn’t have seemed new,” he says. “There was an altar where people would make sacrifices to ‘Zeus the averter of flies’ because the bugs were so annoying.”

The nudity: Yes, the rumors are true. The track and field events were competed in naked, according to Stewart.

Why? The most common story says that Orsippos of Megara started the practice when his shorts fell off accidentally while he was running in some time around the 7th century B.C. The practice “spread within a century across the Greek world,” Stewart says, pointing out that the word gymnasium is derived from the ancient Greek word for “naked,” gymnos.

“We have no idea why they did it,” he admits, “but once the custom had taken root, it never died—until the end of antiquity, that is.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com