As race relations flare up and crises unfold in America’s streets, the rate at which we create and consume digital content skyrockets. The most powerful and compelling snapshots, news photographs and video footage that rise out of an onslaught of imagery stick in our brains, forming a visual memory or imprint refreshed or strengthened with each successive encounter. Real-time news coverage increasingly relies on images that not only saturate the news—they can influence how events are depicted and remembered for decades to come.

An achingly familiar news cycle began each time America witnessed a tragic police killing, some local unrest or an explosive confrontation throughout this past summer. Local tragedies from Chicago and Baton Rouge to St. Paul, Milwaukee and beyond quickly became national stories. Now, the killings of Terence Crutcher in Tulsa and Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte are trending as disturbing footage and images spread through news and social media outlets.

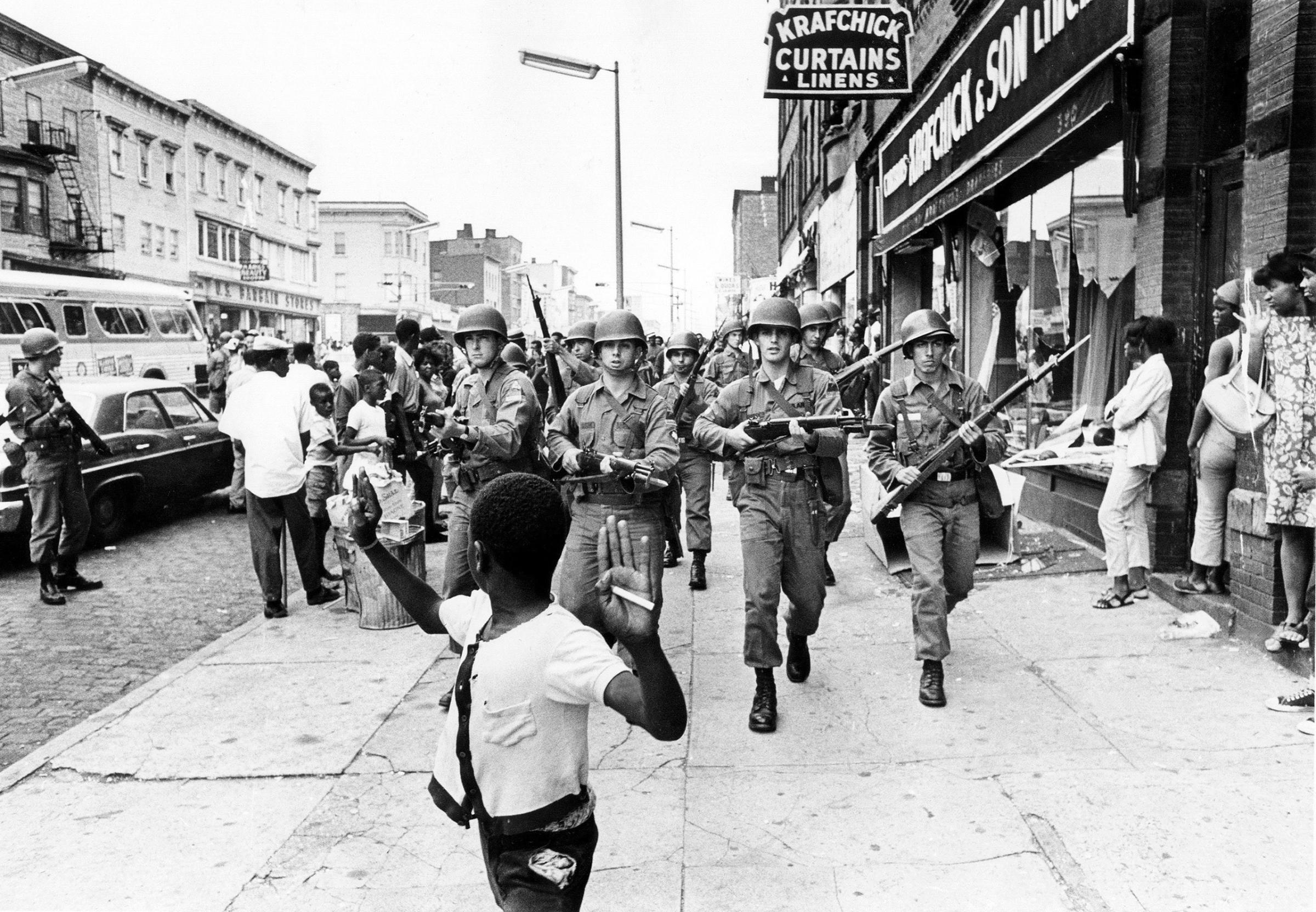

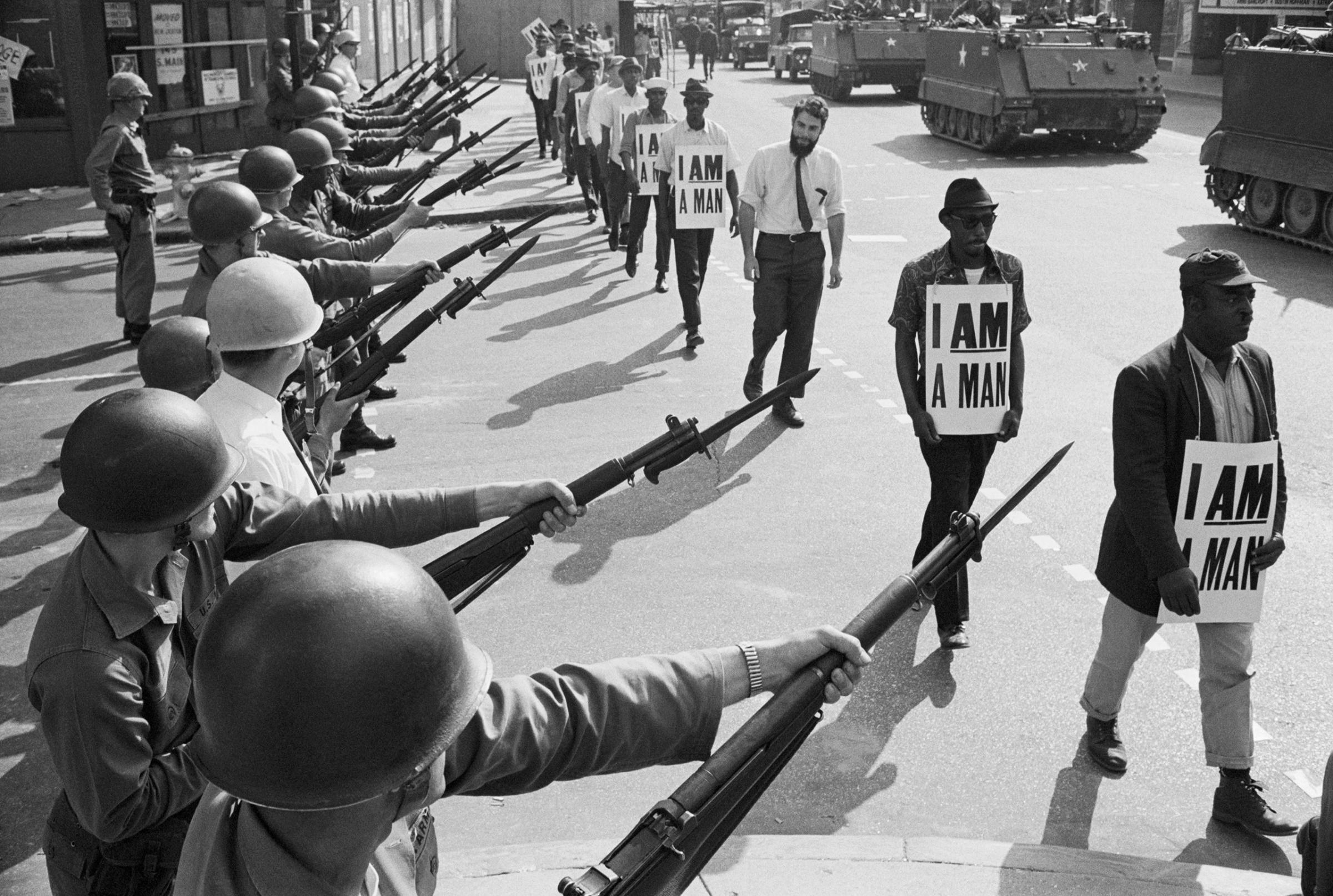

The shootings and explosive protests for justice that follow repeatedly amplify issues of race, profiling, and police violence against minorities. Black Lives Matter activists denounce the killings, demand accountability and that America acknowledge and reckon with its racist past. Armed with bullhorns, signs, and cell phones, protesters nationwide stage demonstrations, block city streets and highways, and encounter armored police forces bearing military-grade weaponry. Each time a name becomes a hashtag, dramatic pictures by photojournalists, artists, and activists themselves document the historical moment for all the world to see—and share.

Yet, this is more than a moment. The push to make black lives matter equally began coalescing into a loosely coordinated movement following the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman’s acquittal the following summer. Propelled forward with each successive police shooting, campus protest, and campaign against a local injustice, the movement and activists’ diverse goals, demands, and policy platforms represent the “fierce urgency of now” and echo a longer black freedom struggle.

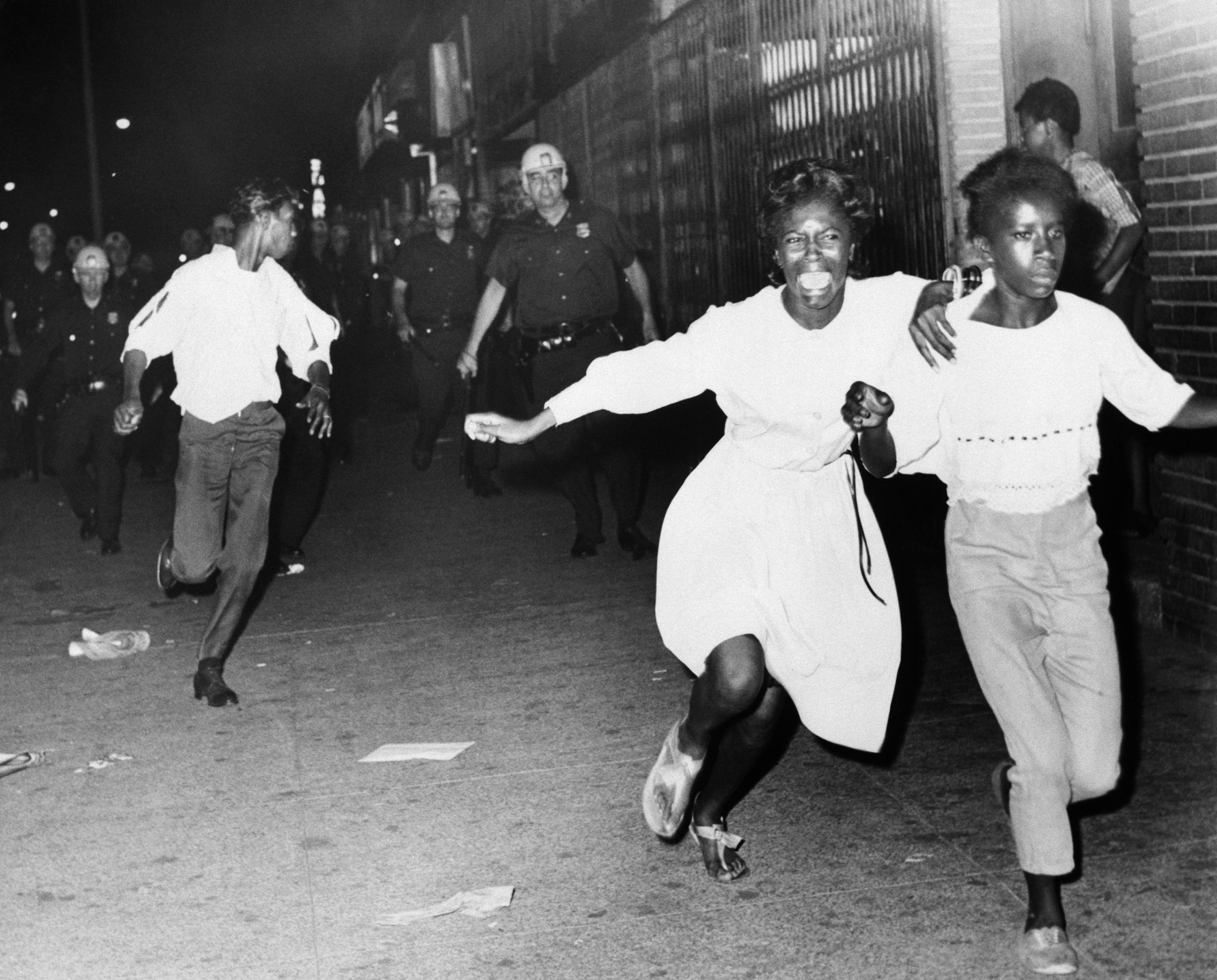

Pictures from Black Lives Matter protests resemble Civil Rights era photography and serve many of the same crucial roles. Photographs documenting meetings, marches and demonstrations convey immediacy and inspire activism. While some images tell stories and illuminate the joys and struggles of everyday people working for change, others reveal how local people and their communities are suffering.

The very best pictures, taken by the likes of Sheila Pree Bright, Devin Allen and Patience Zalanga, command our attention with their sensitive treatment and authentic, often grassroots perspective. Others capture feelings of mistrust, hopelessness and determination during the tense confrontations and make lasting impressions on how clashes are portrayed. Take for example the gripping images of hyper-militarized police force emerging from Ferguson after the killing of Michael Brown or the viral arrest photo of Ieshia Evans, the lone woman in a dress in Baton Rouge. These visual representations represent only a millisecond of a long, contested struggle, but shape how we see and remember these events for years to come.

The astounding amount of imagery documenting today’s marches and racial struggles is enabled, not surprisingly, by technology. The near ubiquity of cell phones ensures that no poignant moment, clever sign, or altercation goes unrecorded. This also speaks to the many vital roles photos continue to play—they can document, preserve, inspire, attest and provide evidence. Equally powerful, video recordings provide real-time coverage of groups staging protests and winding through city streets in order to be heard. Though shaky and raw, live footage provides a ground-level perspective unedited or framed by commercial networks.

But this immense digital output can only make an impact and be seen by others if it is shared through expansive social networks and with ever-changing technologies and apps. Rather than solely appearing in print or on television, the overwhelming majority of images and videos are viewed on screens and devices. The visual impact of a traumatic image is not only sensed and internalized by the viewer—it is instantaneously shared, passed along, and broadcast online.

The gripping pictures documenting and coming out of the Black Lives Matter movement have undoubtedly changed the course of our recent history, just as stirring Civil Rights era photographs did more than five decades earlier.

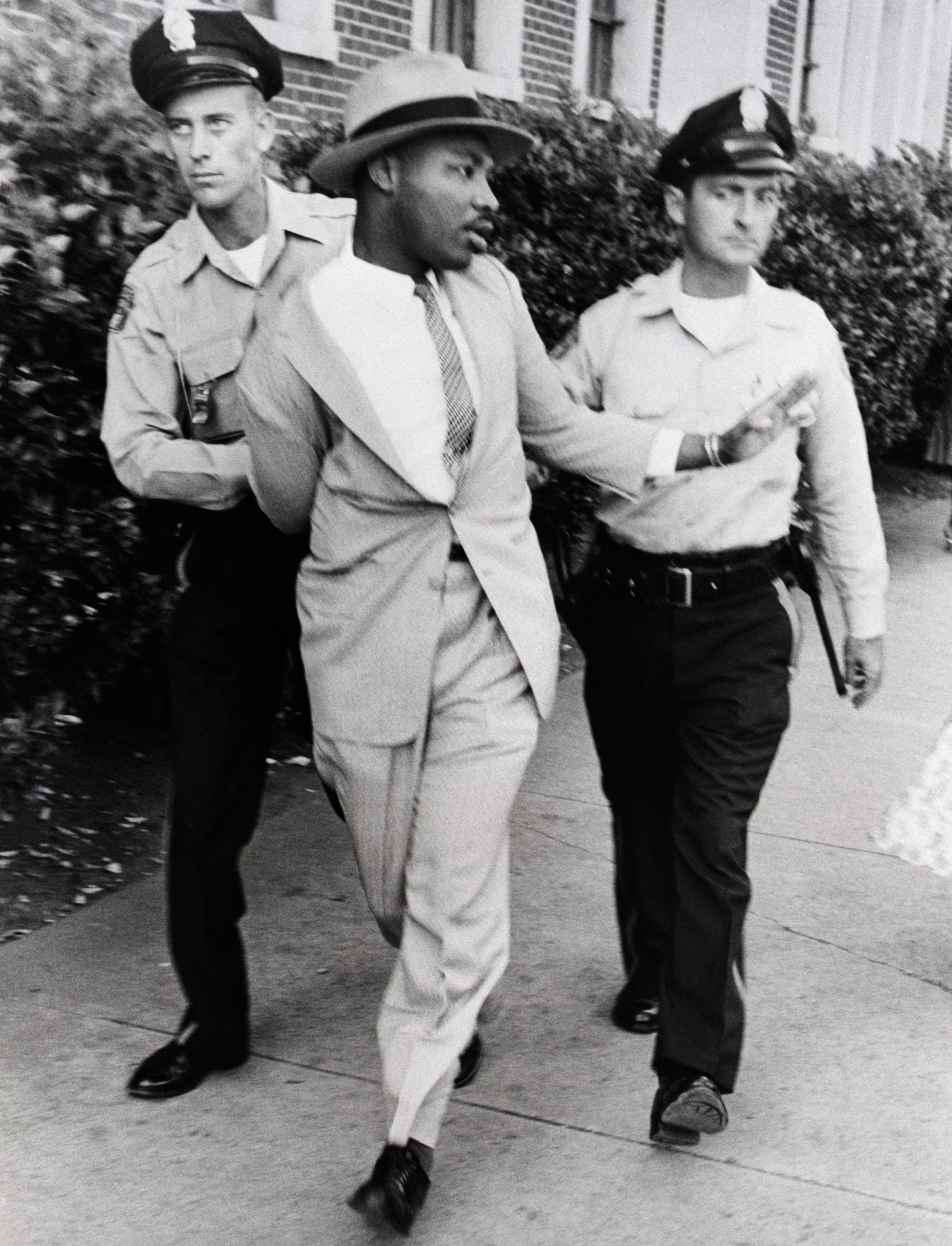

Most Americans today learn about the Civil Rights Movement through photographs. Images documenting speeches by charismatic leaders, dramatic clashes between nonviolent marchers and police, and massive demonstrations form an important archive. Incredibly powerful news pictures from well-known settings, such as Little Rock, Birmingham and Selma, were seared into our nation’s historical memory and imagination. Now, the most iconic images repeatedly appear in history textbooks alongside imagery of George Washington crossing the Delaware River and Marines raising a flag at Iwo Jima. Photographs from modern America’s defining social justice struggle are critical touchstones in the visual narrative of our nation’s past.

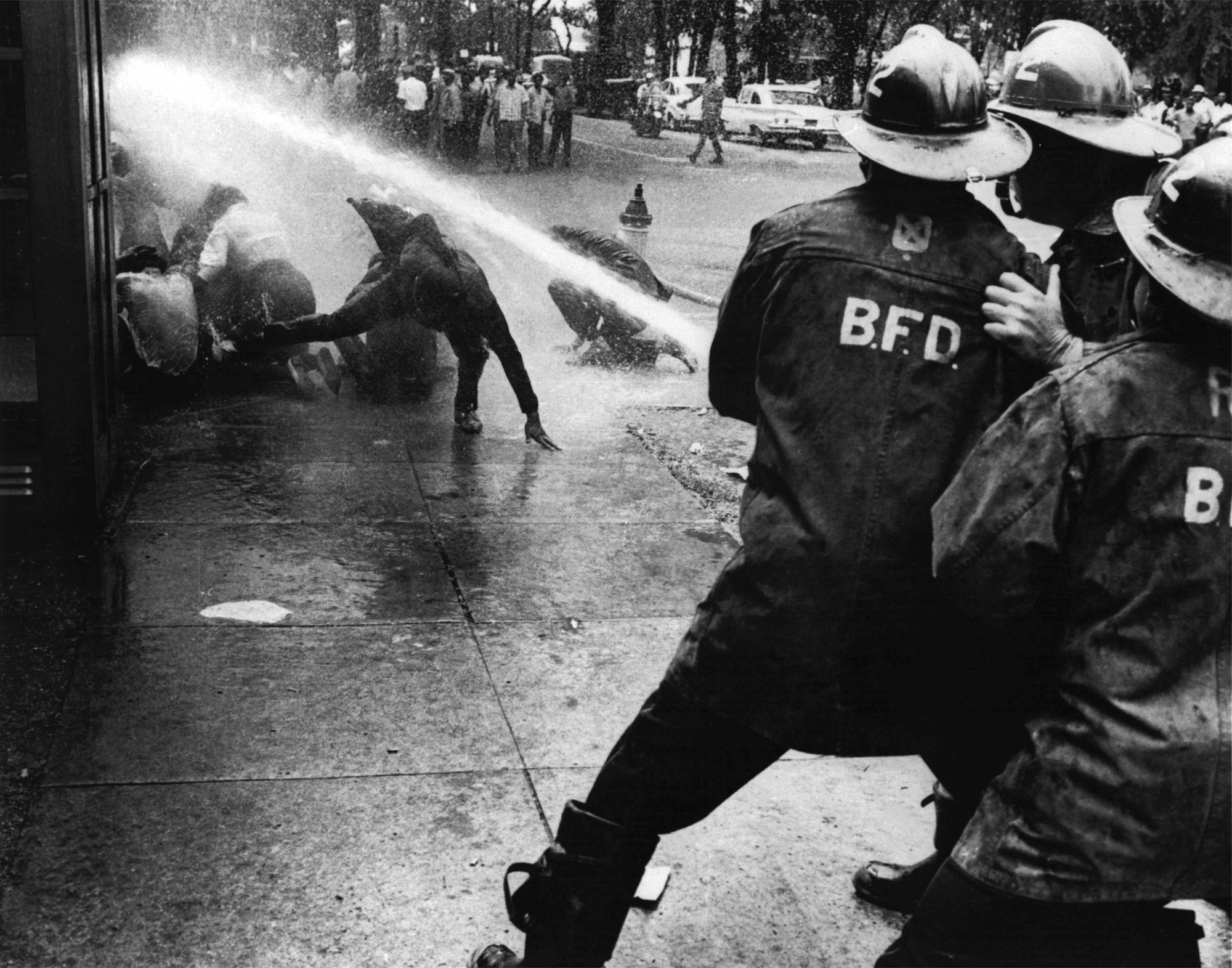

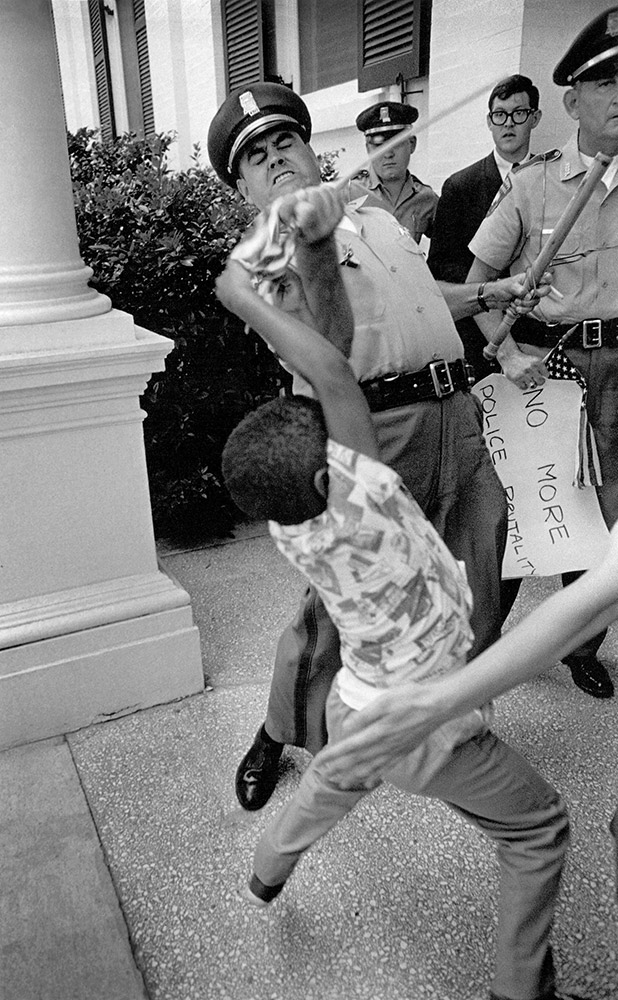

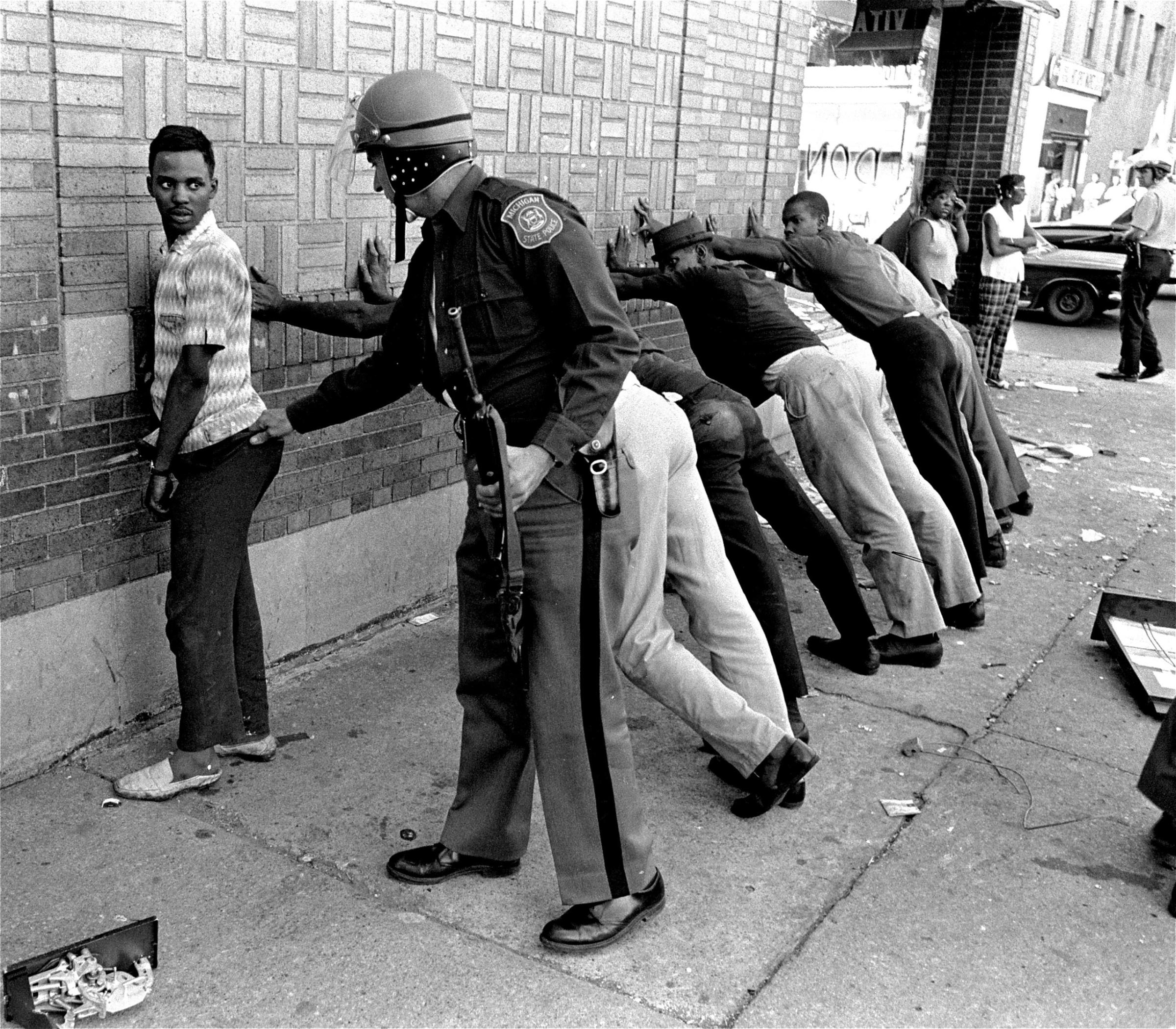

Photography played an important role in advancing the struggle for justice and equality. Compelling pictures on front pages of newspapers and in glossy news magazines raised awareness of the burgeoning movement, while others shocked the nation. Bill Hudson’s and Charles Moore’s news photographs from Birmingham in 1963 captured law enforcement officers’ brutal treatment of largely nonviolent protesters with police dogs and high-pressure fire hoses. Civil Rights organizers understood eye-grabbing pictures could build sympathy for the cause, attract financial support, and prod politicians to offer protection and eventually, enact landmark legislation. Photographic coverage conveyed not only the intensity of the struggle but also made the massive resistance to change visible.

Few today fully appreciate how Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and scores of activists strategized and sought that type of photographic coverage. Yet, no matter how important these photographs were and powerful they remain, solely focusing on images of brutality and violence provides an incomplete picture of the era. Because of this, Americans are less familiar with critical moments of strength, agency and determination.

Photojournalists and activist photographers also documented little-known campaigns from coast to coast with pictures that told even more stories. Organizations shared pictures with sympathetic news publications and filled newsletters, leaflets and fundraising materials with imagery that dramatized the issues and relayed a sense of urgency. Photos of victims battered by Detroit police ran in black-owned newspapers and newsmagazines alongside activists resisting arrest at protests and troubling depictions of poverty and discrimination. Tens of thousands of pictures bore witness to a broad movement—conceived of and advanced by strong, local leaders, including many black women and youth—that actively challenged racism and many forms of inequality that America has yet to overcome.

In 1963, Dr. King and other organizers knew they struck visual gold when snarling dogs and fire hoses were turned against protesters in Birmingham. Film crews and photographers swarmed the scene, transmitting the vicious response to direct action protests far and wide. Groups today, however, no longer need to hope for and primarily rely on this type of news coverage. By coupling time-worn strategies and tactics with new technologies, today’s activists are able to frame the struggle, shape their own visual representations, and amplify their grievances and hopes for a new America more freely and farther than the most media-savvy or well-funded civil rights organization could dream of in the 1960s.

Despite the distance of the decades, the moving imagery of the emerging Black Lives Matter movement builds upon a visual narrative of protest and struggle that remains all too relevant in the present.

Mark Speltz is a historian and the author of North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South published by J. Paul Getty Museum. Follow him on Twitter @mespeltz.

Liz Ronk, who edited this photo essay, is

![Rodney King;George Holliday [Misc.] Rodney King beating by LA cops in 1991.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/10-rodney-king-1991.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com