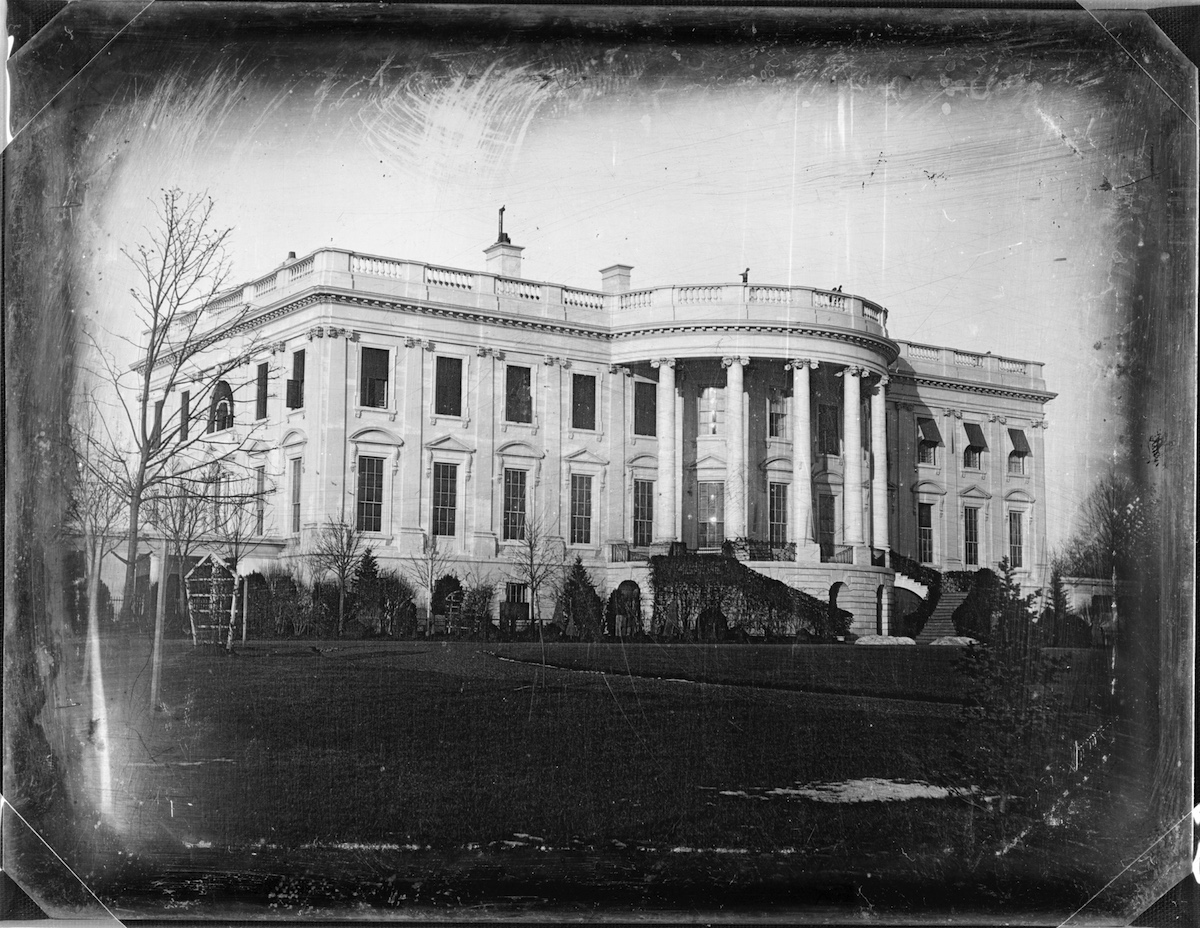

Following Michelle Obama’s reminder to Americans that she wakes up every morning in a house built by slaves, the White House Historical Association on Wednesday released an updated explanation of the role of slaves in the history of the residence. And, while recent attention has largely focused on the executive mansion’s construction, the overview highlights another facet of that past: seven U.S. presidents owned slaves during their time in office there.

Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Tyler, Polk, and Taylor all owned slaves while living in the White House.

In fact, slaves were lodged at the White House far past its construction. Jefferson was the first to bring his slaves — a dozen of his household servants from Monticello — to 1600 Pennsylvania. After Jefferson, Madison brought slaves from his Virginia estate. The earliest known account of slavery in the White House, Paul Jennings’ A Colored Man’s Reminisces of James Madison, comes from that period. In it, Jennings recounts being moved to Washington, D.C.:

When Mr. Madison was chosen President, we came on and moved into the White House; the east room was not finished, and Pennsylvania Avenue was not paved, but was always in an awful condition from either mud or dust. The city was a dreary place.

Following the building’s destruction during the War of 1812, slave labor was also used to rebuild the mansion between 1814 and 1818. (Nor was the White House the only D.C. landmark built by slaves: in 2012, the U.S. Capitol Building unveiled a plaque commemorating the pivotal role of slave labor in its construction.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In addition to the seven presidents who owned slaves during their terms, four presidents had slaves at other points in their lives: Van Buren, Harrison, Andrew Johnson and Grant. And George Washington owned between 250 and 300 slaves during his presidency, according to the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies, though he left office before completion of the White House.

When Zachary Taylor’s presidency ended with his death in 1850, freed African Americans in D.C. outnumbered those enslaved by almost two to one, according to Census Records. That same year, Congress passed the Compromise of 1850, which was meant to end the slave trade in new states.

But it would take another 12 years before slavery was abolished in D.C. on April 16, 1862, with the Emancipation Act, which freed about 3,000 enslaved African Americans. Nine months later, Lincoln signed the more widely recognized Emancipation Proclamation of 1863.

For decades after the end of the Civil War, African Americans held an annual Emancipation Day parade in D.C. to demand the full rights of citizenship. A century later, in 2004, D.C. made Emancipation Day a legal holiday, to “symbolize for Americans the triumph of the human spirit over the cruelty of slavery.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com