When a faction of the Turkish military launched a doomed attempt to overthrow the elected government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on July 15, the government immediately blamed the followers of Fethullah Gulen, a controversial religious leader who lives in exile in the United States. The anti-coup protesters who faced down soldiers in the streets of Istanbul seemed to agree. As tanks blocked bridges and warplanes circled overhead, in the city’s Taksim Square, demonstrators held a hand-painted sign reading, “The demon is in Pennsylvania”—a reference to Gulen’s residence in the Keystone State town of Saylorsburg.

The government says Gulen’s followers have built a vast network within Turkey’s bureaucracy over the decades, tantamount to a state within a state that compliments the 75-year-old Gulen’s worldwide network of businesses, charities, and schools. Gulen’s network is a self-proclaimed “humanistic” Islamic movement that preaches altruism and charity. However analysts, Turkish officials, and former affiliates say the movement is a deeply hierarchical and secretive sect. In the wake of the failed coup attempt, the authorities have now detained at least 15,846 people accused of ties to the coup plot or to the Gulen movement, according to Interior Minister Efkan Ala. Gulen himself denies any link to the coup plot. On Wednesday the government also issued arrest warrants for 47 journalists, all former executives and employees of the formerly Gulen-affiliated Zaman newspaper. Turkish authorities also ordered the closure of 45 newspapers and 16 TV stations.

Read More: Turkey’s Long Night of the Soul

The U.S. government is still evaluating Turkey’s demand for Gulen’s extradition, and some American officials are privately skeptical of the Turkish government’s account of the coup. But inside Turkey, the accusations against Gulen offer a point of consensus for the country’s disparate political camps. For broad sections of the Turkish public—even those opposed to Erdogan—Gulen is a villain the country can unite against.

Turkey’s predominantly secular opposition has long seen Gulen as a dangerous cult leader. For Erdogan and his Islamist-leaning government, Gulen is a former ally who betrayed them in 2013, spawning a bitter rivalry and a struggle for control over state institutions that has played out for at least two and a half years. At the same time Gulenists make a useful target for Erdogan—blaming them avoids a possible confrontation with the staunchly secular and nationalist military leadership whose predecessors have staged previous coups in Turkey far more successful than the one attempted earlier this month.

“He is at this point what unites the country. There is no one who would stand by Gulen. I mean, he’s done,” says Burak Kadercan, an expert on Turkish politics at the U.S. Naval War College in Rhode Island. “It’s a very convenient story. It just exonerates the secularists of any involvement. They can claim that they’re anti-coup, not necessarily pro-Erdogan, but anti-Gulen for sure.”

Turkish officials now say the attempted coup was a preemptive strike in response to a plan to remove roughly 100 military officers suspected of ties to Gulen. The cull of the military brass was to come at a biannual meeting of the Supreme Military Council (known by the Turkish acronym YAS) that usually takes place in August. The summit is now taking place on July 27, moved up by a few days in response to the failed coup attempt.

An official from the Turkish prime minister’s office said plans to remove suspected Gulenists from the armed forces leadership had been in motion for about six months. Speaking on condition of anonymity, he says the suspected officers, including generals, had been recruited by the Gulen movement as much as 20 or 30 years ago and worked their way up through the ranks. “They were really well hidden,” says the official in a phone interview.

A second official from the president’s office confirmed a preexisting plan to remove the officers. “There were plans to discharge them from the military. Our assessment is that the ongoing effort has led them to attempt a coup,” he says by text message. Both officials spoke on the condition of anonymity in accordance with government protocol.

The government has produced some evidence to support its claims. For example, Hulusi Akar, the chief of general staff, reportedly testified that the officers who detained him the night of the coup offered to put him in touch with Gulen. Dani Rodrik, an economist at Harvard’s Kennedy School who has studied Gulenist involvement in the Turkish state, says it is possible that the documentation of Akar’s testimony could have been doctored, but it appears authentic in his view.

More broadly, while it is impossible to verify claims of the extent of the alleged Gulenist faction in the military, experts who study the movement say there is some evidence of a significant presence within the armed forces. “Nobody really knows,” says Rodrik. “What’s more important is the degree to which Gulenists have been able to control key points: they have been in charge of the legal department of the military for example, and their sympathizers are disproportionately represented among aides-de-camp of the most senior generals. There is good reason to believe that a majority of the officers promoted after 2008-2009 have been Gulenists.”

Coup Attempt in Turkey Ignites Night of Hell

Complicating the government’s narrative is evidence that the coup plotters joined forces with secular Kemalist officers, those who adhere to the principles of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the modern Turkish republic. The official from the prime minister’s office said “two or three” Kemalist generals had joined the coup plot. The statement released by the plotters on the night of the failed coup stressed Kemalist themes like “secular and democratic rule of law” and made reference to “extraordinary sacrifices led by the Great Atatürk.”

Owing to those complications and others, some observers remain wary of the government’s account of the coup plot, and the near wholesale blame put on the Gulenists. “There’s plenty of circumstantial evidence accordingly, but the neat and tidiness of the narrative, and how quickly it was packaged, I just find to be at worst just a little suspect, a little organized in how this all went down,” says Joshua D. Hendrick, a professor of sociology at Loyola University Maryland and the author of a book on the Gulen movement.

Read More: Turkey’s Instability Calls the E.U. Migrant Deal Into Question

For Erdogan’s government, the sweeping clampdown on the Gulen movement marks the climax of a political drama of almost Shakespearean proportions. When it first came to power in 2002, Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (known by the acronym AKP) allied with Gulen and his followers, who offered a network of bureaucrats, and the infrastructure of a social movement, including respected schools, after school programs, and numerous charities. The two movements appeared compatible, both professing a mild brand of quasi-Islamist politics.

That alliance came to an end in December 2013 after alleged Gulen-linked officials launched a corruption probe that implicated officials in the AKP government, sparking a feud between Erdogan and Gulen, who was already living in self-imposed exile in the U.S. By April 2014, Erdogan was accusing Gulen of plotting a “coup” and urging the U.S. to deport him. The government began to remove suspected Gulen affiliates from government positions. “This is a fratricidal tug-o-war, whereby the worldviews are so aligned—it’s the reason why it’s so vicious,” says Hendrick.

Read More: Turkey Could Be Taking A Big Step Backwards In Human Rights

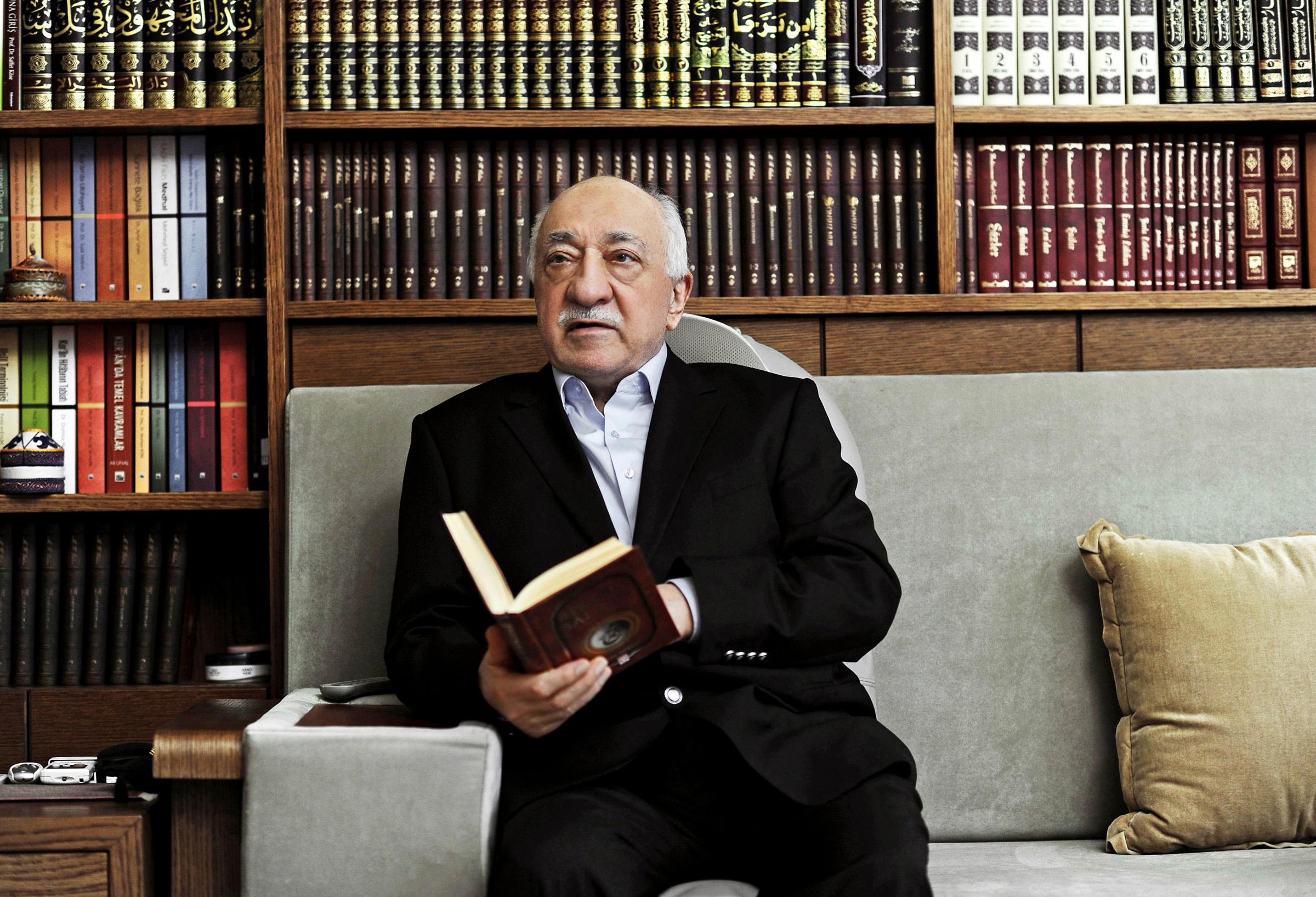

From his retreat in the Pocono foothills of Pennsylvania, Gulen continues to deny the accusations that he triggered the coup, including in a recent opinion column in his name in the New York Times. “My philosophy—inclusive and pluralist Islam, dedicated to service to human beings from every faith—is antithetical to armed rebellion,” he wrote.

Gulen’s denials will fall on many deaf ears within Turkey, where even Erdogan’s opponents view Gulen and his movement with hostility. According to the State Department Turkey’s demand to extradite Gulen is under consideration while legal and technical proceedings unfold. “Left-wing analysts and political commentators in Turkey also hate Gulen almost as unanimously as Erdogan,” says a 28-year-old Turkish professional in Istanbul who is an alumna of Gulen-affiliated educational programs and who since broke with the movement and also describes herself as an opponent of the government, and who asked to have her name withheld out of concerns of reprisals.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com