Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time . com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

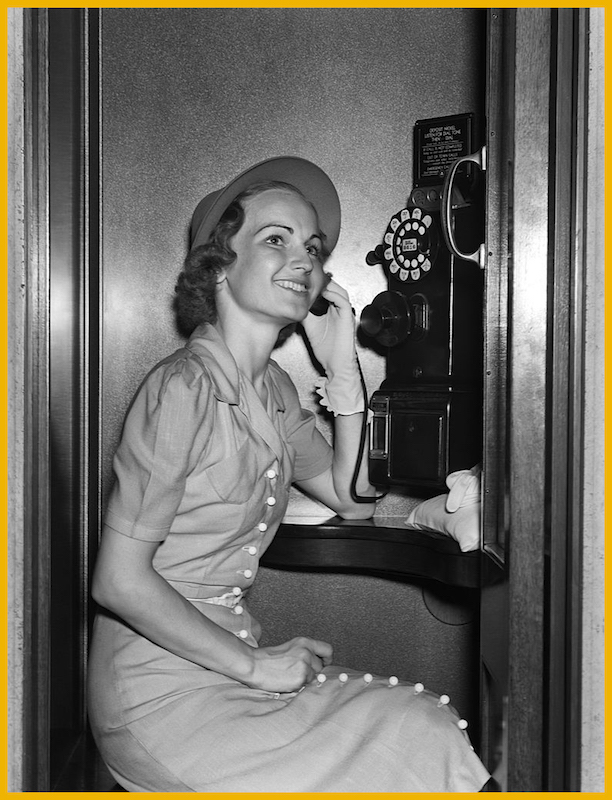

These days, the history of the phone booth seems to be coming to an end, at least in American cities. Widespread use of mobile phones has made it less and less necessary to provide another way for people to make or take a call while out and about.

But where did this disappearing equipment first appear?

To unravel the whole story of where the first telephone booths and pay phones were located, TIME turned to Sheldon Hochheiser, corporate historian at AT&T, who says that the first step is to separate pay phones from phone booths.

“In the early years these are two totally separate questions,” he says. “You can have a booth with a telephone in it, and the telephone can not have anything to collect coins; you can have a telephone designed to collect coins, but not in a booth.”

When the telephone was invented in 1876, it was at first a service available only to the relatively wealthy, at least when it came to private use. As Hochheiser explains, phone service was sold to individuals in expensive monthly packages. But, as the telephone grew in the years after its invention, so too did the demand for a way to access the telephone exchanges—services that connected people via operators—even if one didn’t have a private telephone in one’s business or home.

One of the earliest commercial telephone exchanges was established between Bridgeport and Black Rock, Conn., in 1878. That year, Thomas Doolittle had also re-used a telegraph wire between the two towns and “put a telephone on each end and put them in wooden booths” Hochheiser says, which people could pay a set rate of 15 cents to use, making that perhaps the first telephone connection that was both in a booth and where people could pay to make an individual call, as Connecticut Pioneers in Telephony records. The first proper “telephone cabinet” was patented in 1883, and it was a fairly elaborate affair: intended to measure a roomy four by five feet, with a desk inside and wheels to move the whole thing. Though there’s no clear information about where the very first telephone one was installed, Hochheiser says “they typically would have been in places like high class hotels.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

But in 1889, a new solution to the public telephone problem came in the form of a coin-operated public telephone that was installed in a bank in Hartford, Conn. Created by William Gray, who had previously invented an inflatable chest protector for baseball umpires, it was the first machine that collected the cost of the call, with no attendant. Though there’s no evidence it was in a booth and though it wasn’t the first time people were paying to make individual telephone calls, it was a milestone nonetheless—and perhaps the first phone that would be recognizable to a person familiar with modern public pay phones.

According to a history put out by the Gray Telephone Pay Station Company in the 1930s, years after Gray had died, he came up with the idea in 1888, when his wife was ill and he needed to get the doctor. “He doesn’t have a phone in his home, which is not surprising,” says Hochheiser. So Gray went to the nearest place where he knew there was a phone, a factory down the street. But they initially refused to let him use the phone, as he wasn’t a subscriber. Though the factory eventually allowed it, when he explained why he needed to use the phone, the experience made an impression.

“This got him thinking there had to be some way to allow people who didn’t have phones in their homes to make a call without having to pay” for a monthly subscription, says Hochheiser. He came up with a series of experimental models, submitted a patent application in 1888 and on Aug. 13, 1889 was issued a patent for his device. Soon he formed the Gray Telephone Pay Station Company and, along with another inventor named George Long, made a series of improvements.

The idea caught on. Gray’s obituary in the Hartford Courant called it his “crowning invention,” adding that “the invention popularized the telephone, which had become a business necessity and is now almost a household necessity, and made it possible to use the telephone in a public manner in public places without the necessity of an attendant,” and that it was quickly adopted by phone companies.

The earliest coin-operated phones, including the Gray phone, “were post-pay on an honor system,” as Hochheiser puts it: “you made the call and when you were done, since all telephone calls required operators, the operator told you what coins to deposit.” The coins would hit a bell, creating a sound the operator could hear to determine if it was the correct amount. Pre-pay systems were developed near the turn of the century and 1909 saw the development of a mechanism to return the coins if the call didn’t go through.

The 1911 Model 50A coin operated public telephone, manufactured jointly by the company Gray founded and Western Electric (AT&T’s manufacturing division), brought many of these features together. Within a year or two of their introduction, 25,000 of them could be found in New York City alone. “They were installed on subway platforms,” Hochheiser says, “anyplace where it was likely that someone would be who would need to make a call. There were banks of them in Grand Central Station and Penn Station.”

Outdoor phone booths made their first entrance in the early 1900s, and became commonplace in the 1950s when glass and aluminum replaced difficult-to-maintain wood as the building material of choice.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com