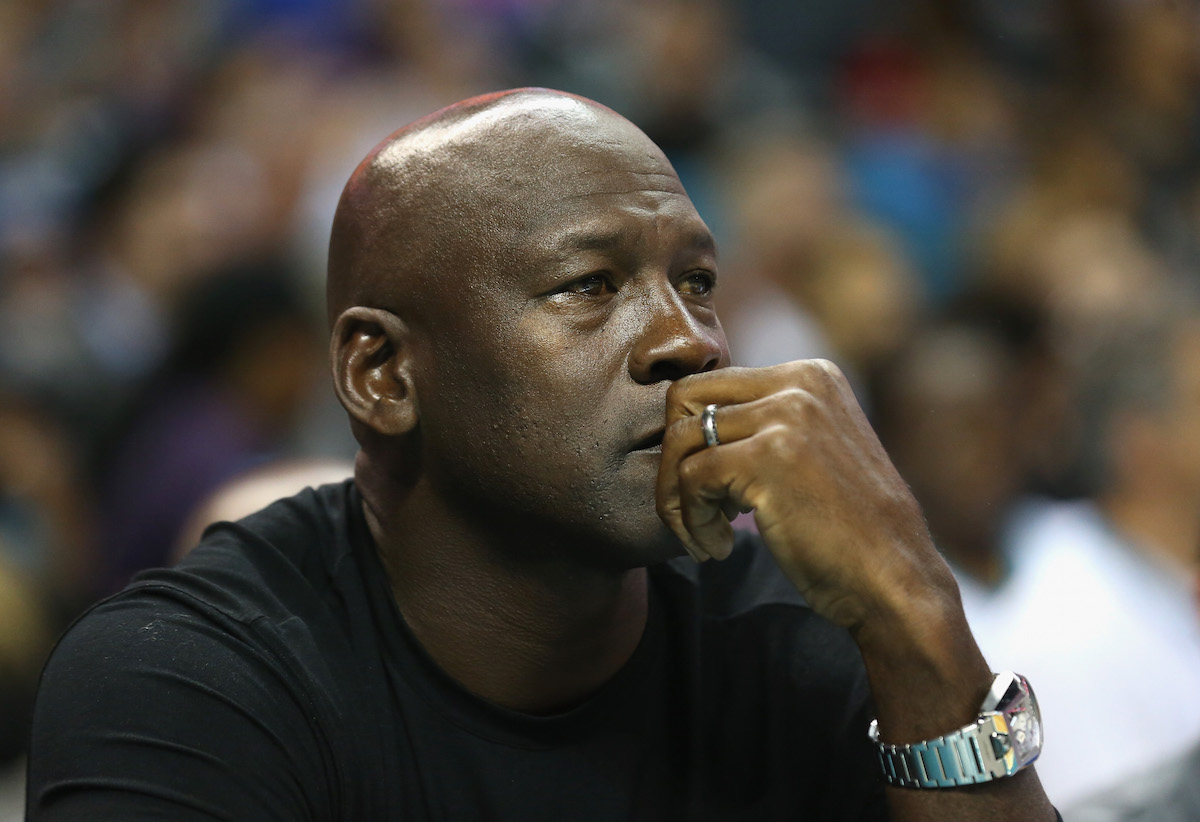

In 1990, during a heated North Carolina Senate contest between the incumbent, ultra-conservative Republican Jesse Helms, and Harvey Gantt, the African-American Mayor of Charlotte, Gantt’s campaign approached NBA superstar Michael Jordan for an endorsement. Jordan declined to endorse, allegedly quipping that “Republicans buy sneakers too.”

Jordan’s refusal to endorse drew the ire of many in the African American community—and 25 years later, he still had not lived down that infamous moment. In a 2015 interview, athlete-author-activist Kareem Abdul-Jabbar chided his colleague stating, “You can’t be afraid of losing shoe sales if you’re worried about your civil and human rights. He took commerce over conscience. It’s unfortunate for him, but he’s gotta live with it.”

This week, in light of the continued violence plaguing the nation, Jordan decided he could “no longer stay silent.”

On Monday, in an exclusive statement published by The Undefeated, a blog focused on the intersections of sports and race, Jordan described his reaction to recent police shootings, and the ways in which his own experience has made him both appreciative of law enforcement and concerned about the injustices experienced by people of color. “As a proud American, a father who lost his own dad in a senseless act of violence, and a black man, I have been deeply troubled by the deaths of African-Americans at the hands of law enforcement and angered by the cowardly and hateful targeting and killing of police officers,” he wrote. “I grieve with the families who have lost loved ones, as I know their pain all too well.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Indeed, on Aug. 4, 1993, the corpse of James Jordan, Michael Jordan’s father, was found among the branches in Gum Swamp just across the South Carolina border from Robeson County. Two weeks prior, on July 23, 1993, the elder Jordan, who resided about 120 miles southwest in Charlotte, N. C, was returning home from attending the funeral of a friend in Wilmington. He parked his cherry-red Lexus Coupe alongside the road at a country store off of U.S. highway 74 to rest.

Carjacking was on the rise during that time. Whether in urban, suburban or rural America, and no matter the make of the car, no one was exempt. Carjacking was up 25% in 1992, from the previous year, wrote TIME’s now-Editor Nancy Gibbs in a story that summer. “Car crime is no longer a matter of stealing parts but of taking lives,” the story noted.

James Jordan being fast asleep at a closed business on a lonely country road made him an easy victim.

And the Jordan family’s suffering didn’t stop there: At the same time that they learned of the murder of their loved one, they also learned that Marlboro County, S.C. coroner Tom Brown, citing lack of space, had ordered the body autopsied and cremated within three days. Dental records received a week later positively identified the John Doe as James Jordan.

Years later, boyhood friends Daniel Andre Green and Larry Martin Demery were both sentenced to life in prison for the murder, after trials that revealed that the two had come upon the Lexus and shot the elder Jordan point blank in the chest with a .38 caliber handgun. He died instantly. It had not been hard for the police to identify the killers. The pair had videotaped themselves with a watch, golf shoes and a replica NBA championship ring from the Bulls’ 1990-1991 season, all items that belonged to the deceased. In addition, the two had placed calls from the car cell phone, which was a major clue in helping police in their capture

According to an April 2016 article in the Charlotte Observer, lawyers for Green, who was identified by Demery as the shooter, are now requesting a new trial based on evidence that has raised questions about his 1996 conviction.

Jordan’s personal experience not only motivated him to make an historic statement, but he has also pledged $1 million each to the International Association of Chiefs of Police’s newly established Institute for Community-Police Relations and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “Although I know these contributions alone are not enough to solve the problem,” Jordan stated, “I hope the resources will help both organizations make a positive difference.”

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com