There wasn’t much glamour in an Apollo command module. The ship was little more than an 11-ft (3.3 m) tall conical capsule that served as home to a trio of astronauts for most of their trip to and from the moon. It had a habitable volume of just 210 cubic ft. (5.9 cu. m), which is like packing three grown men in a minivan for history’s longest road trip .

But it was a magnificent ship too—none more so than the Apollo that got the numeral 11. That, of course, is the one that carried Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin out to the moon for history’s first lunar landing, 50 years ago this month. The spacecraft has spent most of the years since on display, encased in a protective plastic shell at the Smithsonian Institution’s national Air and Space Museum, affording a look inside through its windows and open hatch, but providing no real sense of what it was like to be inside. Now that’s being remedied, thanks to a 3D experience you can try here, created by the Smithsonian and its collaborator Autodesk, a company that specializes in cloud-based 3D design.

Removing Apollo 11’s plastic hatch cover for one of the few times since the spacecraft went on display, technicians used 3D visual scanners mounted on booms to capture every cubic inch of the cramped space in which the astronauts once lived. The work involved taking one trillion 3D measurements which produced over a terabyte of data. It is designed to be viewed both in flat screen pan-and-scan and on Google Cardboard, for Android or iPhone.

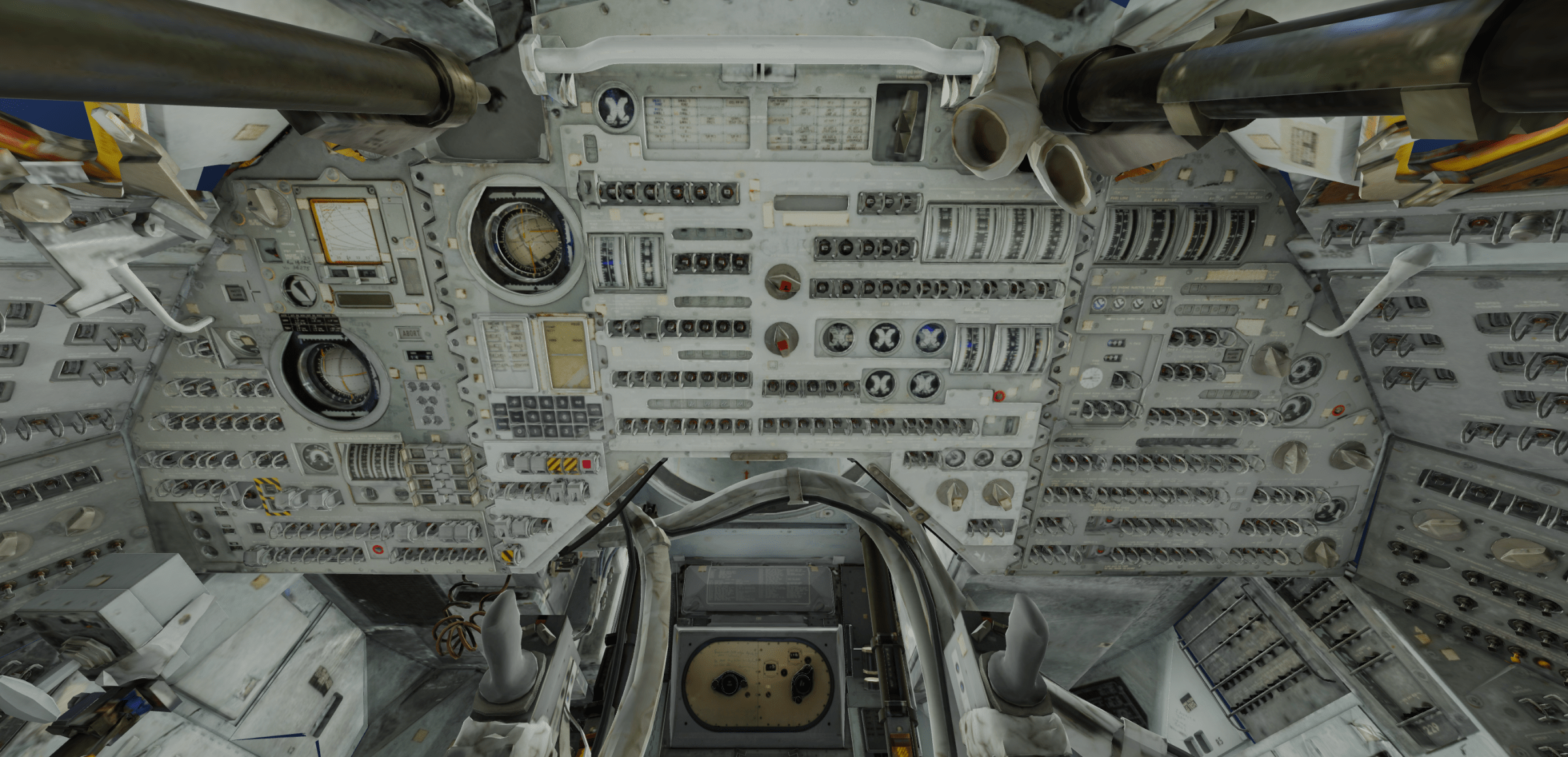

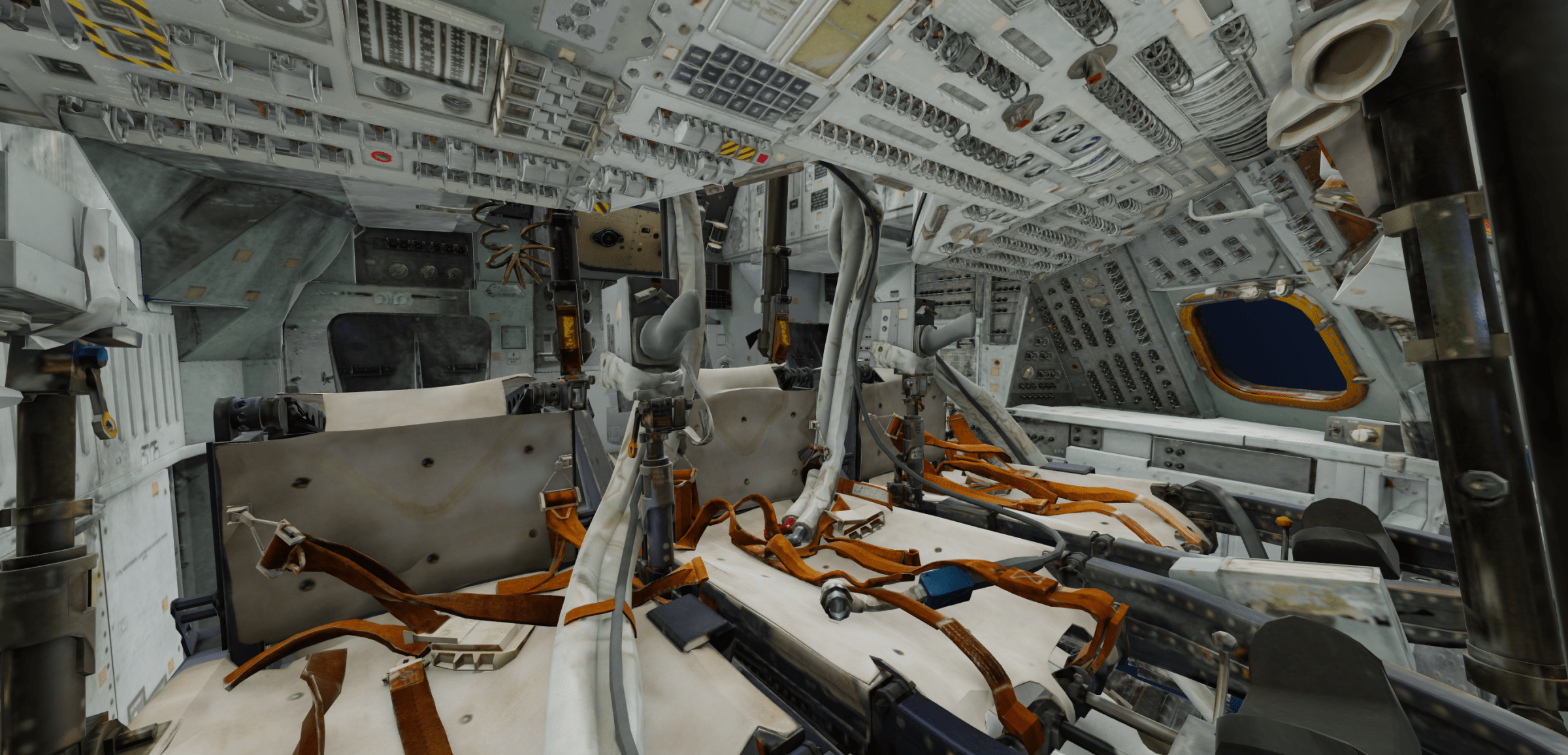

The detail captured by this painstaking work is both extraordinary and immersive. There is the sweeping array of switches, indicator, breakers and knobs that fill the wraparound instrument panel—with their names and functions readily readable. There is the lower equipment bay beneath the seats, where the navigational sextant and computer were located. There are the astronauts’ cloth and canvas couches and the five windows through which they first glimpsed the moon and the closed tunnel in the nose of the spacecraft that once connected to the lunar lander.

And, as with so many places humans go and things they touch, there is graffiti: a calendar indicating every day the mission flew—July 16 through July 24, 1969. There are random numbers scribbled on the bulkhead, as one or the other of the astronauts, without a flight plan or scrap of paper handy, jotted down some coordinates Houston read up to them.

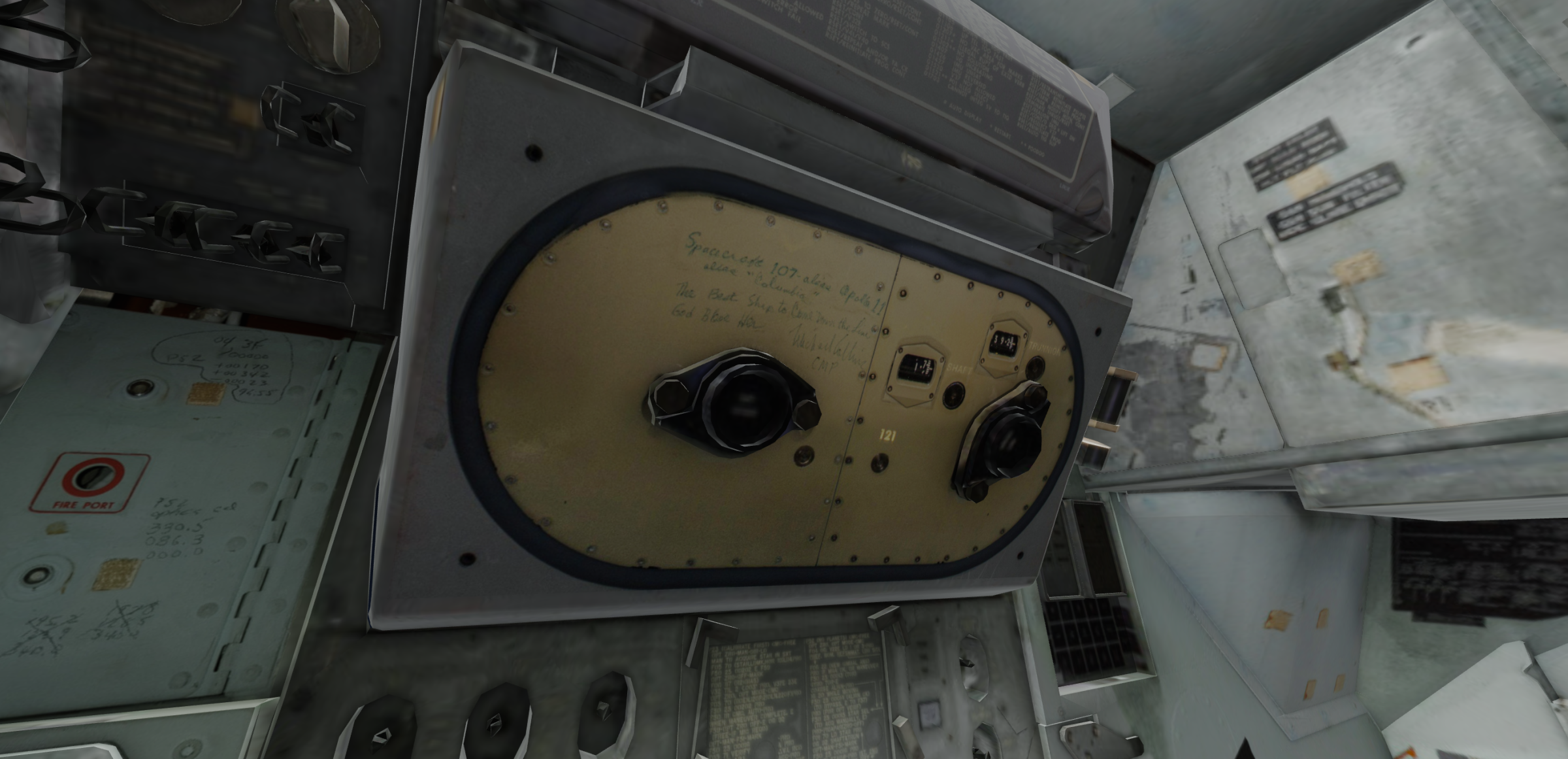

And there is, most evocatively, a tribute written by Collins, the command module pilot—or CMP—who stayed aboard Columbia while Armstrong and Aldrin flew off in the lunar module Eagle to land in the Sea of Tranquility. The two moonwalkers were destined to become history’s headliners on this particular mission, while Collins would always be thought of as something of a supporting player. Still he flew this ship well and he flew it with care and he left behind some words that show that.

“Spacecraft 107, alias ‘Apollo 11’ alias ‘Columbia,” he wrote on a panel in the equipment bay. “The best ship to come down the line. God bless her. Michael Collins CMP.”

Almost no one on the planet had seen those words since the day in 1969 when Collins wrote them. Now we all can.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com