If there is a national Rorschach test for this strange political season, it might be this: Do you recognize the America that Donald Trump described Thursday night?

Murders spiking in our cities. Criminals taking potshots at police officers. Illegal immigrants infiltrating once-peaceful communities. Terrorists lurking. The America of Trump’s acceptance speech at the Republican convention was not the proud and vibrant democracy to which politicians typically pay tribute at moments like this. It was more like an ominous hellscape.

“Our convention occurs at a moment of crisis for our nation,” Trump said as he capped off the four-day event in Cleveland. “The attacks on our police, and the terrorism in our cities, threaten our very way of life. Any politician who does not grasp this danger is not fit to lead our country.”

Listen closely to this bleak message and you may hear echoes of the past. Republicans have long found success by promising to restore order in a dangerous world. In 1968, Richard Nixon harnessed a “silent majority”—a phrase resurrected on Trump campaign placards—in a nation wracked by race riots. In 1988, George H.W. Bush ran his infamous Willie Horton ad, tying his opponent to a black murderer who raped a white woman during a weekend prison furlough. In 2004, George W. Bush ran as the President who could keep you safe from terrorism in a scary world.

But nobody has ever played this game quite like Trump. If his campaign has a dominant narrative thread, it has been describing an American dystopia and promising a return to greatness.

He began his campaign by warning of criminals pouring across the southern border. At rally after rally, he invoked the murder of a beautiful blond woman in San Francisco, allegedly by an undocumented criminal, and that of a promising high-school football star by a gang member.

He ended the nominating process by turning a four-day party into a fiesta of fear. It began with testimonials from three mothers of children murdered by undocumented immigrants. And it was marked throughout by cries to put Hillary Clinton in prison. “In this race for the White House, I am the law and order candidate,” Trump declared.

In the week’s marquee speech at Quicken Loans Arena, Trump talked about a 21-year-old woman who was murdered by an illegal immigrant the day after graduating college. “One more child to sacrifice,” he said, “on the altar of open borders.” He invoked images of blood-soaked streets and “the chaos in our communities.” The “crime and violence that today afflicts our nation,” he promised, “will soon come to an end.”

If the language was a tad dramatic, that may have been part of the plan. “A little hyperbole never hurts,” Trump explained in The Art of the Deal. On Thursday he poured on more than a little. The raw facts are technically true. But they lack important context. Violent crime rates have been dropping for decades, plunging by more than half since they crested in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 2014, the most recent year for which full data is available, the rate was 366 reported violent crimes per 100,000 people, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation—down from 758 in 1991.

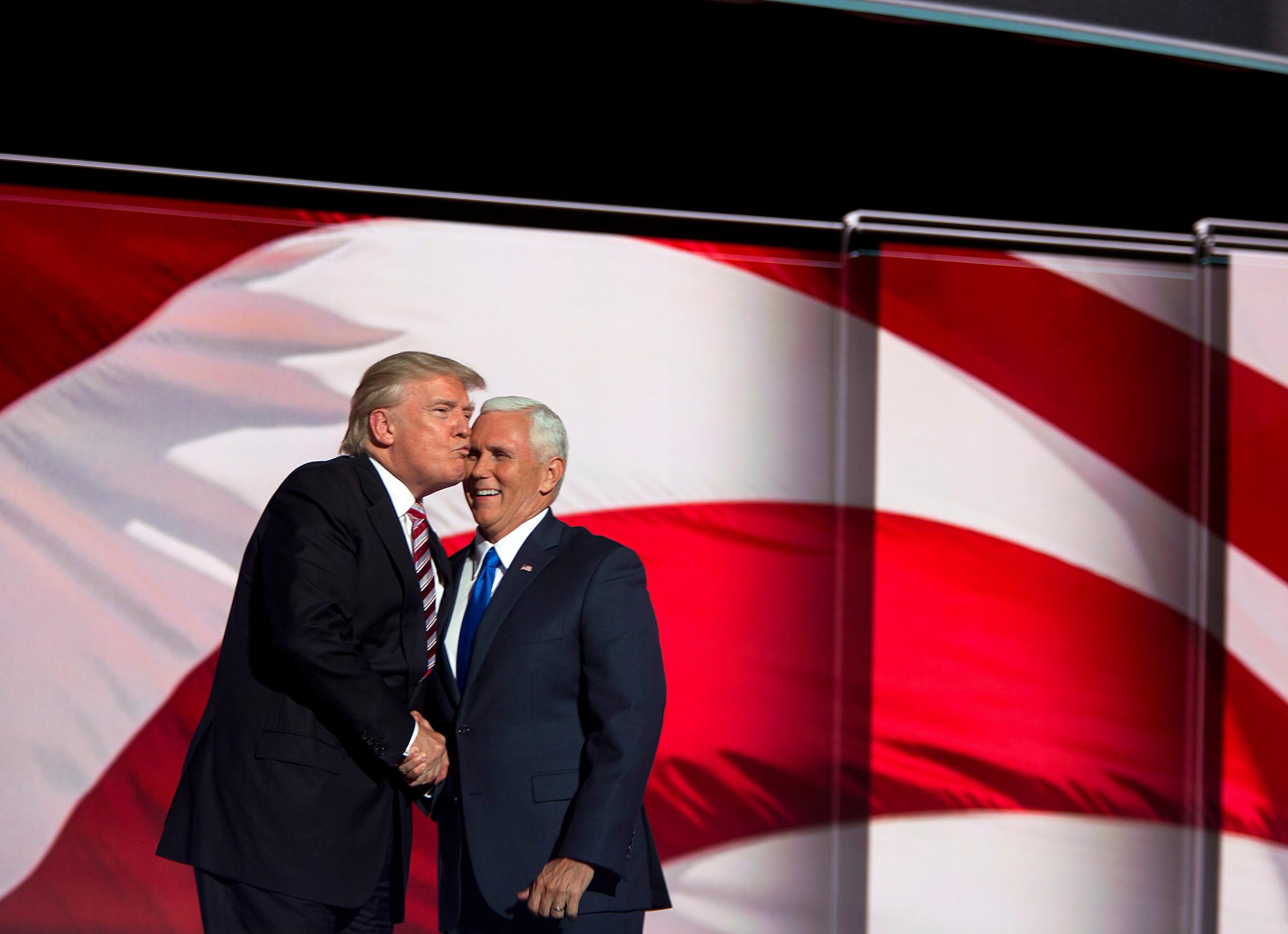

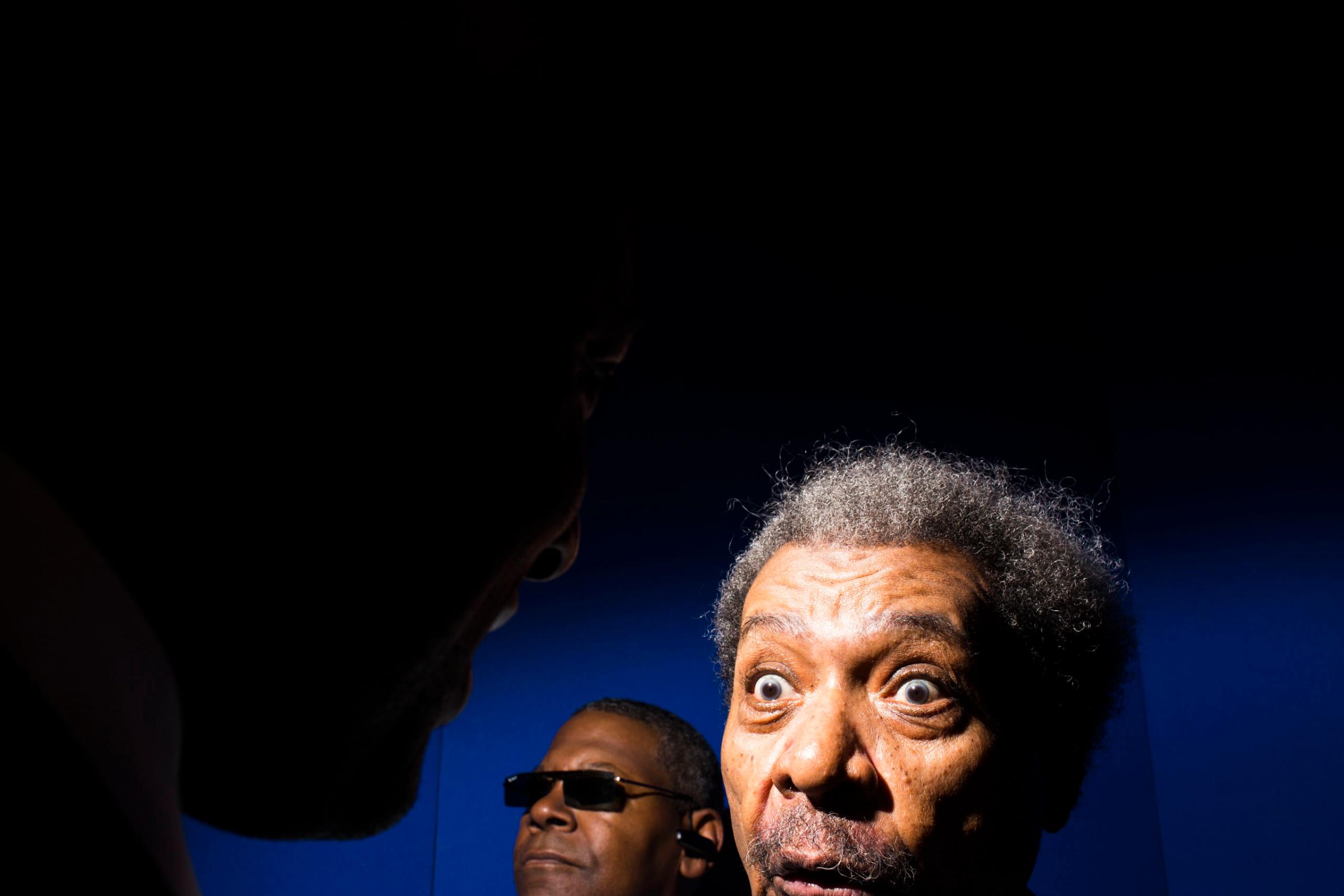

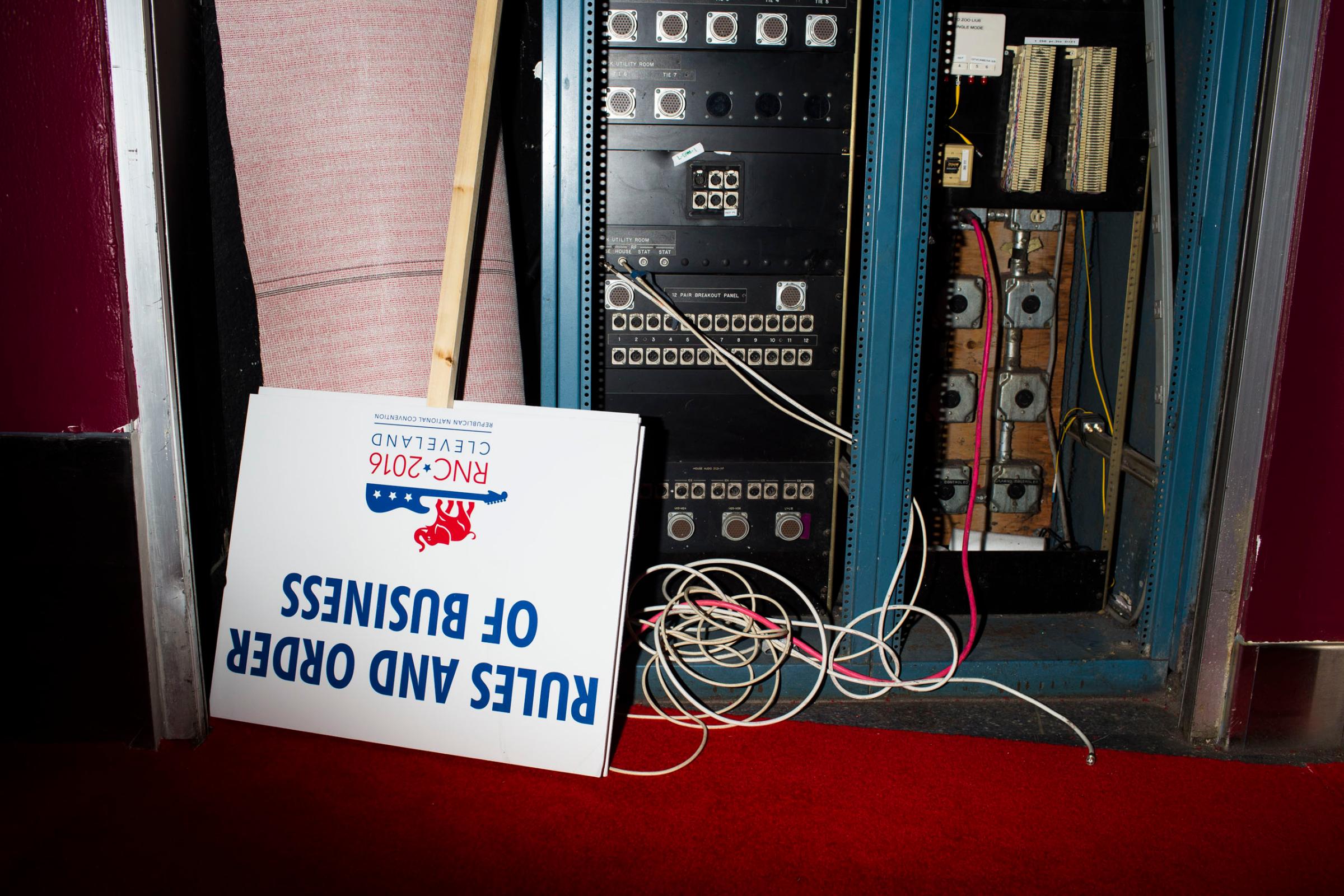

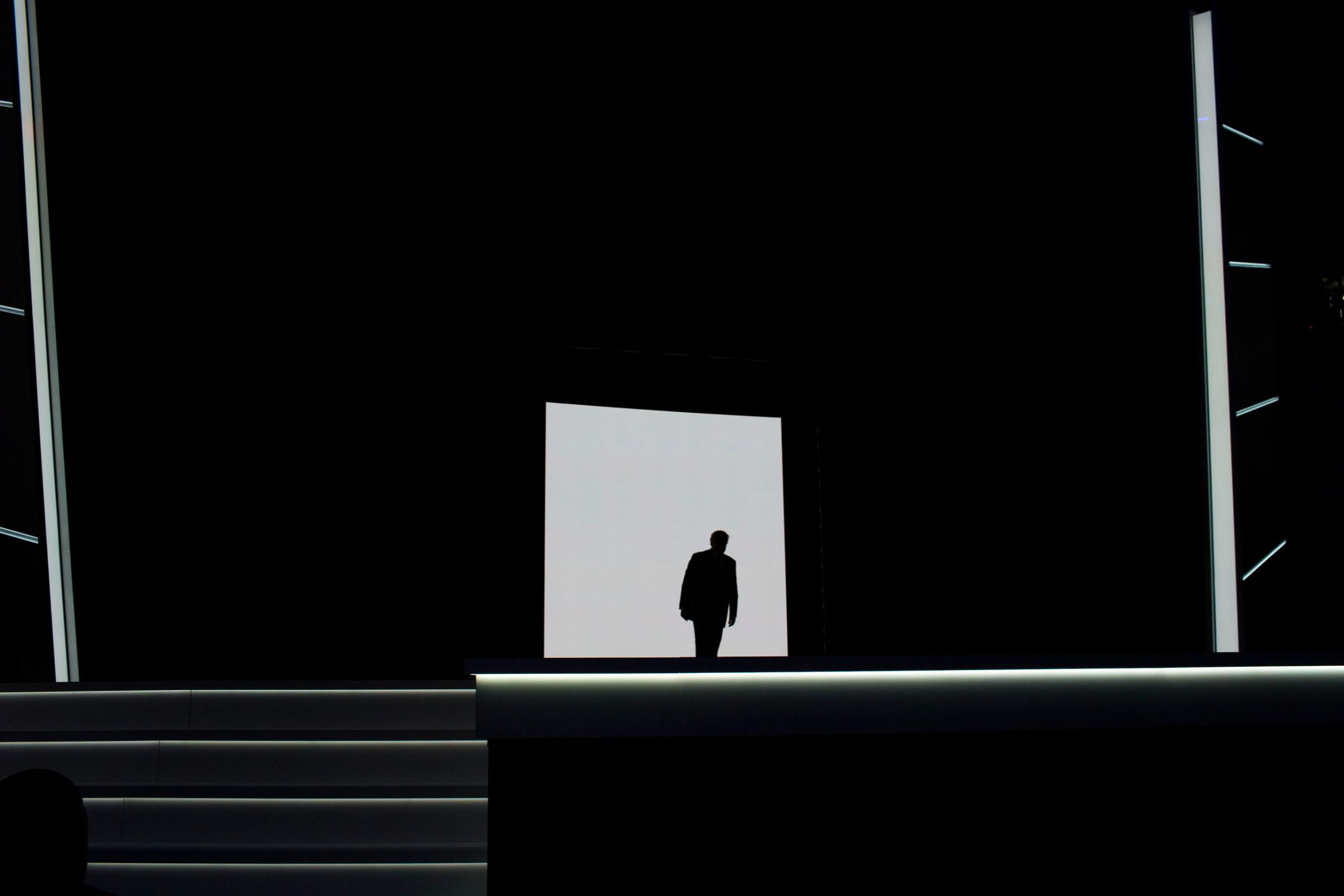

Scenes from the Republican National Convention

“Overall, crime rates remain at historic lows,” said Ames Grawert, counsel in the Brennan Center’s Justice Program. “It’s true that some cities saw an increase in murder rates last year, but it’s too early to say if that’s part of a national trend.”

But the politics of fear can be powerful enough to persuade even those who see little of the turmoil Trump described. On the floor of the convention hall, Michael McDonald, the chairman of the Nevada Republican Party, explained that the Silver State doesn’t have a safety problem. “But in other states you can’t walk, you can’t drive,” McDonald said. “If you don’t have that thin blue line protecting America, we’re done.” Craig Prince, a delegate from California, explained that “we have no clue who’s a terrorist. They have no desire greater than to kill us, kill Americans, kill our way of life.”

Like all speeches, this one was as notable for the points it didn’t make as those it did. A few short years ago, the GOP campaigned on fiscal discipline and free markets. These cornerstone conservative principles were glossed over in Trump’s speech. He used the words “Obamacare,” “the Constitution” and “budget” one time apiece. Long a favorite GOP target, the IRS didn’t rate a mention. Neither did entitlement reform. In the age of Trump, the Tea Party and its calls for ideological purity feel like relics of a bygone era.

When Trump finished retailing “the plain facts that have been edited out of your nightly news and your morning newspaper,” he made the pivot to painting himself as the redeemer. “Nobody knows the system better than me,” he said, “which is why I alone can fix it.” Instead of “yes we can,” Trump’s tribe chanted “yes, you will” from stands packed for the first time all week.

The past few presidents have each been stylistic contrasts to their predecessors. In 2008, Barack Obama’s acceptance speech in Denver was full of gauzy promise and soaring uplift. He praised “the enduring power of our ideals” and promised that “our union can be perfected.” Trump’s first task as President, he said Thursday, “will be to liberate our citizens from the crime and terrorism and lawlessness that threatens their communities.”

That sure ain’t hope and change. But for a year now, Trump has packaged this fear and pitched it to mostly white, working-class voters who feel victimized by rotten trade deals and ripped off by a rigged political system. If you recognize this dystopian America, it could be a powerful sell.

With reporting by Charlotte Alter, Haley Edwards and Sam Frizell/Cleveland

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Alex Altman/Cleveland at alex_altman@timemagazine.com