At first blush, it makes little sense for a libertarian like Peter Thiel to speak for Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention. On Thursday night in Cleveland Thiel explained his support, but he didn’t mention one thing the two billionaires have in common: disdain for a free press.

Both have aggressively used the courts to go after reporters. Trump, who has banned several media organizations from his campaign events, even wants to change libel laws so he can more easily sue his antagonists. So far, though, Thiel is the more effective of the two. Last month, Gawker Media filed for bankruptcy protection thanks to a $140 million invasion-of-privacy lawsuit brought by Hulk Hogan—one of several Thiel has funded. Thiel’s lawyer even threatened a lawsuit over a story about Trump’s hair.

Whatever you think of Gawker’s decision to publish a sex tape of an aging wrestler, Thiel’s victory raises a disturbing prospect: that individual billionaires, rather than society at large, will decide what reporting is in the public interest. Tellingly, Thiel has described his campaign as “philanthropic,” even though he has a personal stake in the result. He resents Gawker for outing him as gay and issuing repeated takedowns of his fellow entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley.

This contempt for an adversarial press has implications that reach far beyond stories about sex tapes or hairpieces. After a critical investigation by Mother Jones, a billionaire named Frank VanderSloot similarly pledged $1 million to support anyone who wants to sue the magazine. The journalist Jane Mayer, after profiling the Koch brothers, discovered that they had hired a private detective to dig into her past, and that a dossier of her supposed plagiarism had been sent to various media outlets. The examples go on.

So how do we ensure that journalists keep telling stories that the very rich don’t want told? The only solution is to write more critical stories. The alternative can be observed in countries where billionaires already command outsized power to shape how they’re covered.

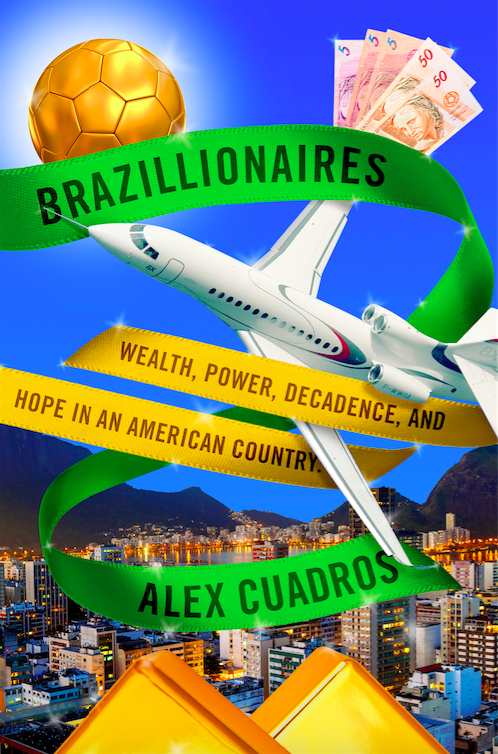

I witnessed this firsthand as a journalist based in São Paulo. While researching a book about the billionaires of Brazil, I ran afoul of the country’s richest man, Jorge Paulo Lemann, a buyout tycoon who co-owns several American brands: Budweiser, Burger King, Kraft, and Heinz. When I asked his press people hard questions about his campaign donations and use of tax havens, they reacted with indignation, because Lemann is held up as an example of meritocratic success in Brazil. I have yet to see a critical story about him in the local press.

Lemann is also said to be unconcerned with his image. And yet my Brazilian publisher soon received a message: He was not happy about my treatment of him.

My book contract was canceled not long afterward. The head of the publishing house assured me that Lemann’s reaction had nothing to do with the decision, and to be fair, the editorial board didn’t like my first draft, which they found overly critical of my subjects. But they had previously said they would wait for the final version before deciding. And their official cancellation letter declared, “As far as Jorge Paulo Lemann is concerned, the animosity is definitely scandalous.”

I can’t know for sure how much Lemann’s message may have influenced my publisher, but my former editor there conceded, “Of course it’s worrying, because you could be getting into a court battle with someone who has 400 million times the firepower that you do.” Lemann and his partners also own one of Brazil’s largest online retailers. (When I asked for an official response, Lemann’s press people declined to comment.)

Pressure from billionaires is rarely so straightforward as Thiel’s campaign against Gawker. Fear of an expensive case can also lead to self-censorship. In Brazil, the unauthorized biography of Lily Safra, a super-rich serial-widow, is banned because of a lawsuit alleging that it defamed a deceased relative. But in the United Kingdom, where Safra has a home, a lawsuit wasn’t even necessary because no publisher was willing to release it in the first place. Libel laws there are especially favorable to a deep-pocketed plaintiff—and if Trump could have his way, they might look similar in the United States.

Approached by journalists outside the secretive Bilderberg meeting last month, Thiel compared the public desire for “radical transparency” to the activities of the Stasi in East Germany. In his view, he and his fellow tycoons are private citizens whose decisions should not be scrutinized. Even if they are unelected, however, billionaires often wield much more influence over our lives than the average politician. Facebook, where Thiel is a board member, has become the de facto gatekeeper of much of the news we consume. It’s thanks to a scoop from a Gawker website that we now know Facebook’s selection methods to be far from neutral, sometimes discriminating against conservative sources.

It’s no coincidence that Thiel has expressed skepticism in democracy itself. What unites billionaires like him, Trump and Lemann, whatever their national origin, is the idea that they know best what we should know about them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com