Edibles on menus or store shelves are not always what they seem. Recently, the international criminal police organization Interpol announced that it seized 2,500 tons of adulterated food in 47 countries—seemingly safe foods like cheese, eggs, strawberries and cooking oil. Even your coffee could be counterfeit; some ground beans have been shown to contain wheat, soybeans, brown sugar, barley, corn, seeds and even stick and twigs.

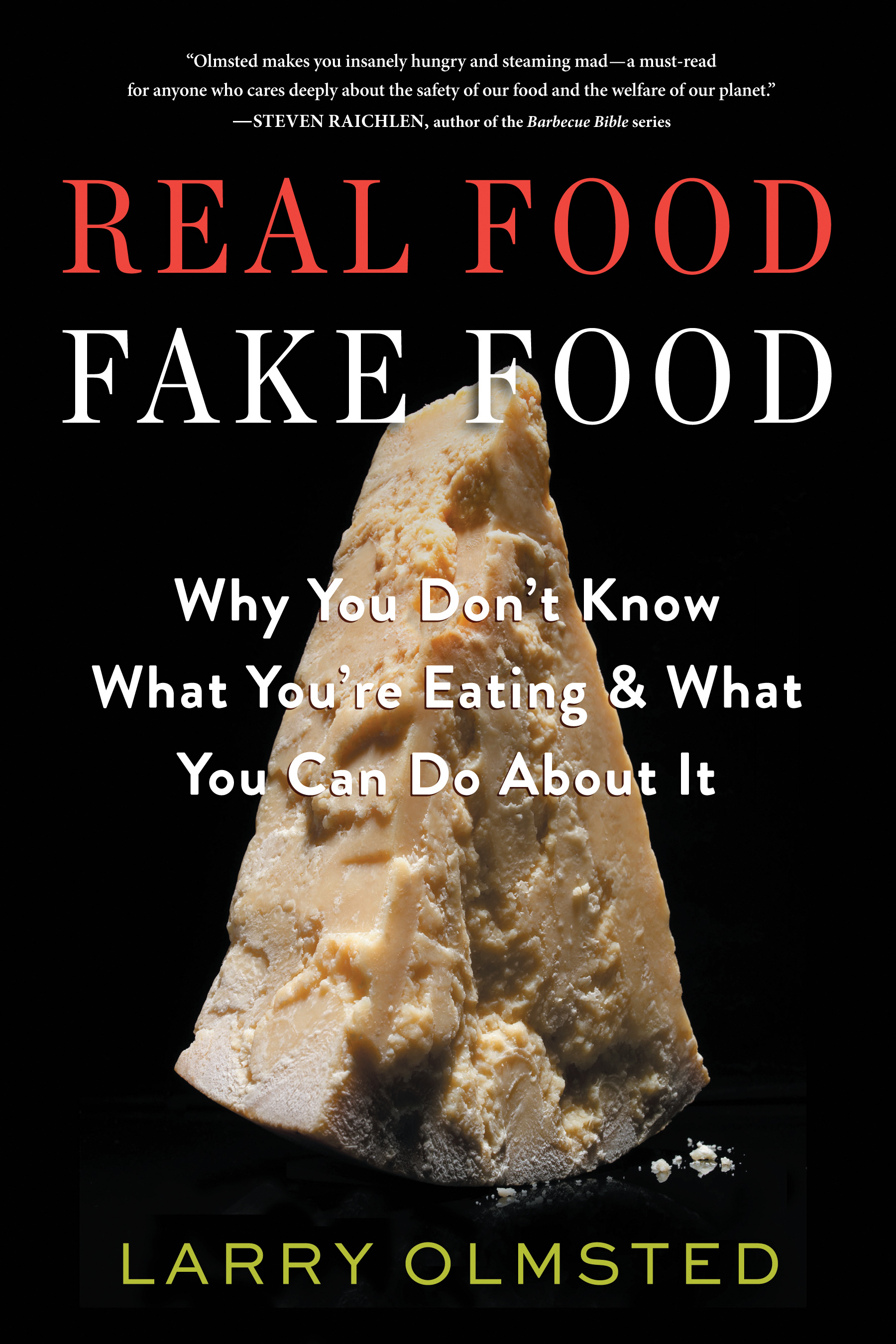

Fraud lurks behind so many different foods, says food and travel writer Larry Olmsted, whose new book Real Food /Fake Food outlines deceptive practices by the food industry in the U.S. and abroad. TIME sat down with Olmsted to discuss foods that are commonly faked and how to make sure you’re getting the real thing.

Fish: “The single most defrauded fish in the United States is red snapper, and the number-one substitute when you think you’re buying red snapper is tilefish,” says Olmsted. Tilefish is on the FDA’s “do not eat” list for pregnant women due to its high mercury content; yet some restaurants sell tilefish disguised as red snapper or halibut and charge a higher price for it. It doesn’t end with snapper, however. 43% of “wild” labeled salmon sold in Chicago restaurants and grocery stores are actually farmed, found a 2015 report from the conservation group Oceana. The fish used in sushi is also frequently not what buyers believe. Olmsted writes in his book that another Oceana study of New York City seafood revealed that 100% of sushi restaurants tested served fake fish and 58% of retail outlets and 39% of restaurants severed fraudulent fish as well. “If there’s one restaurant niche that’s probably the worst, it’s sushi,” says Olmsted.

Olive oil: Many Americans, even foodies, might not have not tasted real, high-quality olive oil, Olmsted says, since fake versions are so common. Olive oil is often diluted with other oils that don’t carry the same health benefits. “It’s usually whatever seed oil is cheapest at the time, like soybean oil, peanut oil, sunflower seed oil,” says Olmsted. In some cases, fake olive oil has had serious health consequences. Olmsted cites a 1981 case in Spain where 20,000 people were poisoned when they consumed olive oil that was actually rapeseed oil with a toxin called aniline. Olmsted says the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is supposed to regulate olive oil and has acknowledged that there’s widespread adulteration of the product that dates back 70 years.

Kobe beef: Authentic Kobe beef comes from a specific type of Japanese cattle that is raised in a unique way that gives the meat a texture Olmsted describes in one fine dining episode as “the textbook definition of tender, with absolutely no chew, graininess, or gristle and a rich, beefy flavor that is almost overwhelmed by its creaminess.” For that reason, it’s also more expensive, and therefore more prone to fraud. Between 2001 and 2012, Kobe beef was banned on and off in the United States because of fears of mad cow disease—so while many Americans think they’ve tried it, Olmsted argues it would have been impossible for quite some time, even if it was on a restaurant menu. In one example, Olmsted writes that the chain McCormick & Schmick’s was slapped with class-action lawsuits when lawyers argued that the chain served meat advertised as Kobe beef during a period when the meat was banned.

Honey: Honey, especially when imported, can be filtered or cut with things like corn or fructose syrup. Certain types of honey are more popular and expensive than others—like manuka honey, found only in New Zealand and part of Australia, says Olmsted—and research has found that honey is often mislabeled as a popular type when it’s not. “The honey industry has been petitioning the FDA to create a standard of identity because it protects them if honey is defined as honey, but the FDA has said no,” says Olmsted. A standard of identity would be a legal definition of what constitutes honey, which some makers argue could prevent misrepresentation from some brands.

How to avoid being fooled: Many government and consumer groups have developed testing and labeling programs for commonly fraudulent foods that can help consumers determine the authenticity of their food. Olmsted says he trusts groups like the Marine Stewardship Council and the Global Aquaculture Alliance when it comes to confirming real fish. But for people who don’t want to spend time reading labels up close, Olmsted has another piece of advice: “The one general tip I give is buy things closer to their whole form,” he says. “If you buy a whole lobster in Maine, you will get full lobster. You buy lobster ravioli, it might not have any lobster in it at all.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com