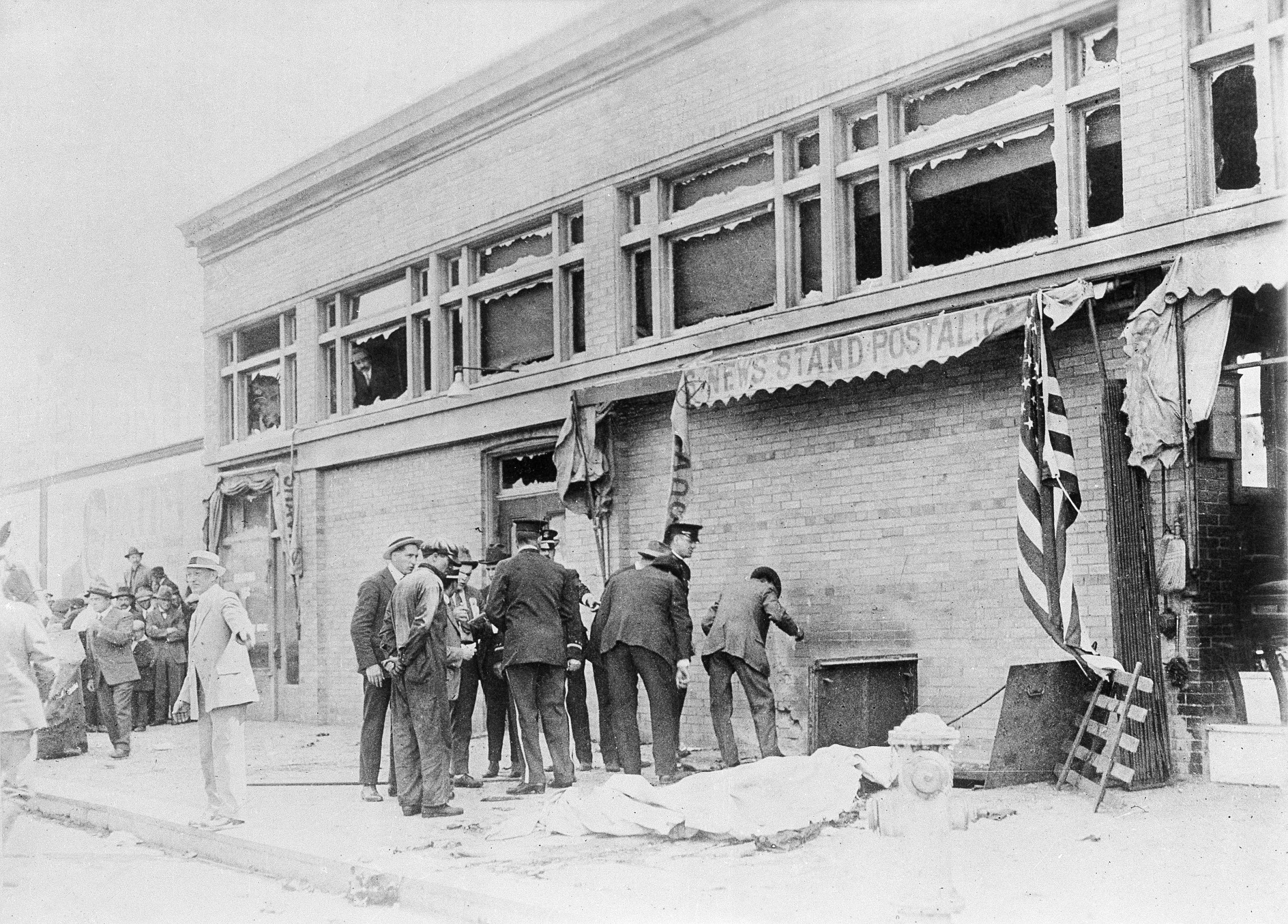

A century ago, the only division in San Francisco more volatile than the San Andreas fault line was arguably the one between the labor union and business communities. These tensions exploded on July 22, 1916, when a suitcase bomb killed 10 and seriously injured 40, per some counts, at the city’s “Preparedness Day” parade—which would be one of the largest parades in the city’s history, if the Library of Congress’s count of 51,000 marchers is to be believed.

The idea behind a “preparedness” demonstration—the likes of which took place nationwide, in cities like New York and Washington, D.C.—was to support bolstering the American military in the event of the nation entering World War I (which, sure enough, happened a year later). But even that idea wasn’t immune from the labor dispute. Some on the left and members of the labor movement saw such parades “as a way for munitions makers to get big, fat government contracts,” says John C. Ralston, author of Fremont Older and the 1916 San Francisco Bombing.

“Part of ‘preparedness’ was a draft, which we didn’t have,” says Jeffrey A. Johnson, history professor at Providence College specializing in radical labor politics, who is writing a book on the bombing, adds, “so if you were member of working class, you were nervous.”

So it was no surprise that, after a bombing that left little evidence behind, socialists, anarchists and pro-labor organizers were the first to be suspected. Detectives and the District Attorney’s office, in cahoots with the city’s chamber of commerce, worked off a list of people they perceived as “troublemakers” from previous strike incidents and those who had ties to radical politics, then went after the ones who were in town that day — an arrangement between business and law enforcement that Johnson said wasn’t unheard of at this time.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Two radical labor activists, Warren Billings and Tom Mooney, were convicted and jailed, with Mooney specifically given a death sentence. Then, as Ralston’s book explains, city newspaper editor Fremont Older broke the story that the prosecution’s primary witness — who testified to seeing the two drive up in a car and leave the suitcase bomb — hadn’t even been in the city and had made up his story with coaching by DA’s office. This violation of basic civil liberties sparked outrage worldwide, including protests by sympathizers in Moscow. In a probe that would continue for more than 20 years while Billings and Mooney were in prison, several commissions produced reports that said there hadn’t been enough evidence to convict the men. “The feeling of disquietude aroused by the case must be heeded, for if unchecked, it impairs the faith that our democracy protects the lowliest and even the unworthy, against false accusations,” declared the federal mediation commission organized by President Woodrow Wilson’s administration.

The men were finally released in 1939. Mooney received a pardon from the Governor of California at the time, while Billings would be paroled and pardoned in the ’60s. Mooney became a labor symbol who would inspire a Woody Guthrie song.

“What you had here was a case of two of very much lesser labor figures no one would really have ever heard of, who were convicted and imprisoned because powerful forces in San Francisco wanted to strike down the labor movement,” Ralston says, “and they seized on two figures as a way of doing this and concocted perjured testimony against them.”

So if Mooney and Billings didn’t do it, who did?

We’ll probably never know. Some theories suggest possible German sabotage given the World War I time period or blame prominent anarchists Emma Goldman or Alexander Berkman (who had a San Francisco newspaper called The Blast). What Johnson is certain of, however, is that 1916 bombing is one example of how extreme tensions between unions and businesses became. But, he says, the incident’s implications are even wider than that. The U.S. within a year or two would “enter a phase of the Red Scare when we get the Espionage Act and Sedition Act and this hyper-sensitivity to ‘loyalty,’ when a lot of rights got really restricted.” Ralston goes as far as to argue that events like the bombing led to the founding of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920.

“The law protects smaller unpopular persons with radical views,” he says, “even as it protects mainstream ones.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com