As the Republican nominee, Donald Trump will be unlike any of his predecessors—a candidate brought to repute by fame in business and television, rather than substantial experience in either the government or the military. But while his Thursday night speech will almost certainly contain hallmarks of Trumpism—brickbats against his enemies, praise for himself—the evidence from recent TV gives reason to believe that he will go through the convention as a more traditional candidate than he’s been.

The convention has, for both parties, a history of delivering a polling bump for the way it makes candidates seem like celebrities for a week; polling aside, this year’s RNC may have the opposite effect on Trump’s candidacy, bringing his fame closer to Earth.

That process was underway in an interview with Lesley Stahl of 60 Minutes on Sunday night, the night before the proceedings in Cleveland were to begin. Trump was, yes, Trump—the fact that this was a joint interview with his vice-presidential pick, Gov. Mike Pence of Indiana, seemed less a fact than a hazy memory, fading back in and out depending on whether Pence was needed to announce that Trump was a “good man” and then get interrupted again.

But Trump’s tone was modulated from that of the primaries, because he didn’t have a field of competitors to mock. The interview found room for a mention of “Crooked Hillary,” but the fact that a wide field of opponents had winnowed down to one meant that the chances for potential provocation had winnowed down, too. Pence’s impact was negligible—his mention at the start of the interview that he was proud to “run with, and serve with, the next president of the United States”—but for the fact that his rigid deference seemed to emphasize the relative calm in Trump’s tone. In an election cycle in which the future nominee skipped a debate because of a beef with moderator Megyn Kelly, sitting through a Lesley Stahl grilling without incident counts for something.

The judgment as to whether or not Trump is or seems “presidential” will be left to the voters. (And, given that every living president, including the two who are father and son, have radically different public personae, the nature of “seeming presidential” may be something made up on the fly.) But the process of framing a too-large personality into a telegenic candidate—in Apprentice terms, turning an Omarosa, the candidate too fun to fire but too wild to win, into a staid leader—is evidently underway.

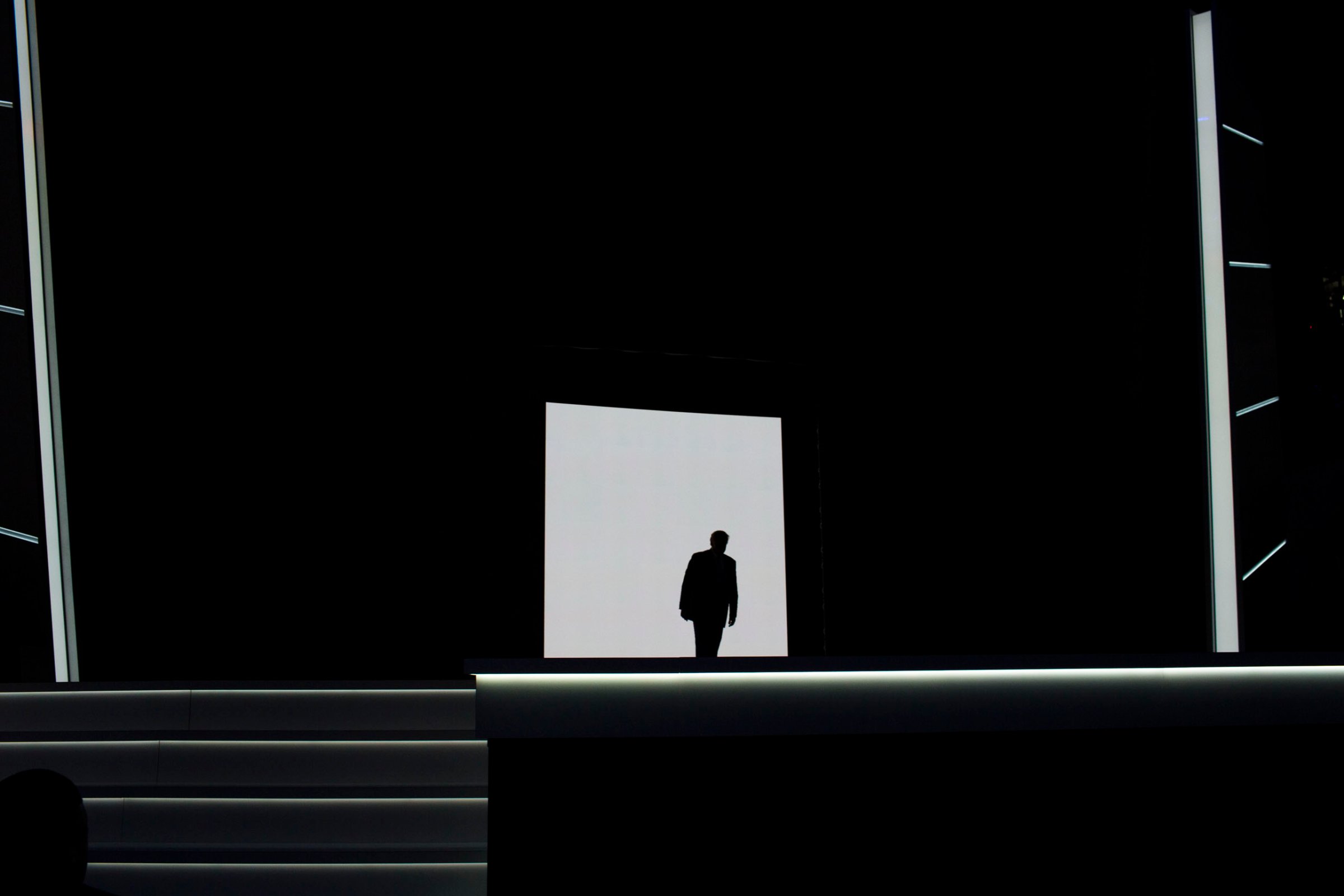

It’s less the work of Trump or anyone advising him than the fact that he’s been caught up in familiar machinery. His vice-presidential choice was vexed—my colleagues at TIME have reported on the behind-the-scenes drama. And yet the announcement itself saw Trump squeezing a giant persona into a framework, with only a little drama extending beyond the edges; a lengthy preamble gave way to Trump ceding the stage to Pence entirely, something those who’ve watched Trump closely couldn’t have imagined a few short months ago. Trump seemed unusually willing to give way to the workings of traditional politics, so much so that he—unthinkably, both to those who think the best and the worst of his self-first ethos—removed himself from the equation.

The evidence for Trump’s media genius to corroborate his electoral success has been The Apprentice, the show where he for years presided over a boardroom of aspirants and chose who to fire and who to, eventually, hire. But the creative force behind that show was less Trump than Mark Burnett, the Survivor mastermind, who created a show whereby Trump could show up and read lines written for him (up until the firing, which was up to him). On that show, Trump was the undisputed star, and he was far more boring than the candidates he was forced to judge between. In a crowded field, Trump is himself an agent of chaos, but he was until recently operating capitalizing upon an unusually chaotic realm—a field of 17 candidates who were firing at each other as well as him. Left on his own, he has little against which to rail; placed in the familiar trappings of a convention, he may be easily tamed.

While it’s hard to view the 60 Minutes interview, governed as it was by a palpable lack of rapport between running mates, as a success in what political operatives call “optics,” it at least represents motion towards the ideal of Trump that many people have in their minds—the free-speaking fellow whose wisdoms and oddities can be contained within a narrow timeslot. The enemies list was down to Hillary Clinton and ISIS.

And while his 60 Minutes interview, limiting though it was in timing and frame of questioning, at least bore some Trump hallmarks (shot at Trump Tower in New York City, the interview had both running mates seated in chairs topped with golden regalia), it also pushed him forcefully closer from “candidate” to “potential president.” A field of 17 candidates pushed into a relentless series of 10-strong debates (with a “kids’ table”) is not a sight with strong precedent in memory for American voters. A 60 Minutes interview with a candidate is, and so is a convention speech, and it’s no surprise Trump grew less freewheeling in the former. I’d guess he’ll be close to—pardon the term—conventional in the latter.

After all, a political convention, even one so vivid in the public imagination for so long that it’s certain to be roiled by protests and already subject to controversy over suspension of “open carry” rules, is a broadcast with customs. These televisual customs have been in place far longer, even, than Trump has been a public figure. Surely the Republican Party cannot and would not govern what Trump will say, but the framework in which he says it—unimpeded at last, on live TV with all but one electoral enemy vanquished—suggests it’ll be his most staid, boring speech yet.

The nominee’s speech at a convention is meant to be the culmination, but usually happens after thunder is stolen—people able to take bigger risks or willing to speak against the nominee go first, before a calm statement of purpose from the chosen one. Donald Trump has, for months, capitalized on the idea that he’s willing to go bigger and bolder than any other candidate, and the other candidates all lost. Trump won the primaries in large part due to the fact that the circumstances created a media story unlike any other in memory.

Now that the story is familiar, Trump has a role to play, and his imagination seems to have its limits.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com