If the Beatles had their McCartney and the 1927 Yankees had their Babe, the Original Seven astronauts had their John Glenn.

That wasn’t the way NASA planned it when the new space agency introduced the boyish, close-cropped, impossibly heroic astronaut team to the country. And it surely wasn’t the way the other six wanted it. It wasn’t even the way Glenn wanted it. A combat pilot and a Marine, he knew a thing or two about how much more powerful an organization can be when the identity of the individual is subsumed into that of the team.

But it couldn’t be helped. Glenn projected something—a pilot’s ruggedness, but a deacon’s decency, along with a charm that the deacon would find nearly sinful. He was part of a profession that not only tolerated bad-boy hijinks, but actually prized them, rewarded them. Men risking their lives, first in combat and later as military test pilots, deserved to play in the time they had to themselves, and play they did.

But Glenn didn’t play—not like that, anyway—and the people he flew with knew it. Even when he tried a little mischief, it just didn’t take.

In 1959, during the carefully staged press conference in Washington, DC, at which the seven astronauts were introduced to the media and, by extension, to the nation, a reporter asked which of the many medical tests the men had endured in order to be selected had been the one they liked the least. It was an open secret that the tests had not only been endless, but entirely humiliating, with remote provinces of the men’s bodies that had absolutely nothing to do with space flight having been subjected to the most invasive inspection.

The question was a hanging curve over the middle of the plate for any pilot with even the mildest taste for the off-color joke. But it was Glenn, improbably, who swung at it.

“That’s a real tough one,” he said, pausing as if to contemplate his answer. “It’s rather difficult to pick one because if you figure out how many openings there are on a human body and how far you can go in any one of them…” He trailed off and then looked at the questioner with a smile. “Now you answer which one would be the toughest for you.”

The audience roared, Glenn gave off a twinkly grin and still the good-boy luster remained.

It was not a sure thing Glenn would get the flight assignment he did, becoming be the first American to orbit the Earth. He might have gotten one of the two popgun suborbital flights that came first, but those went to Al Shepard and Gus Grissom instead. His own flight might not have succeeded—getting part way to orbit and then coming home—which would have made Scott Carpenter, who flew next, the great American spaceman.

But Glenn was the one and he filled the American hero role so naturally, so superbly, that NASA gave him the singular—and yet for a pilot, terrible—honor of deciding that he could never fly again. The nation would sorrow too deeply, the thinking went, if the likes of John Glenn were lost.

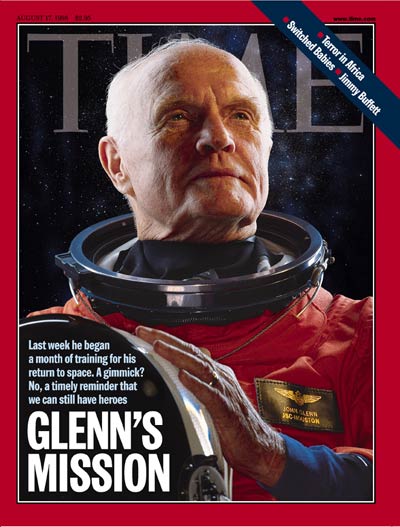

So Glenn, a retired combat pilot, a retired astronaut, would find another way to be of use to his country, and proceeded to serve four terms as a Senator from his home state of Ohio. And he would, despite NASA’s decree, fly in space again too, going into orbit aboard the space shuttle Discovery for a 10-day mission in 1998, becoming the oldest person to fly in space, at age 77. This time, the man who once controlled the stick of every airplane he ever flew, was a back-bencher, a mission specialist while two younger astronauts handled the flying. Unsurprisingly, he did not complain.

Eighteen more years have passed since that mission, and on July 18, Glenn will turn 95. The other six men who wowed the nation along with him—Shepard, Grissom, Carpenter, Deke Slayton, Wally Schirra and Gordon Cooper—are gone. Glenn alone remains.

As with all people, his mortal run—a manifestly extraordinary one—will one day end, and the nation will sorrow then as it would have long ago. We’ve been blessed to have John Glenn for a long, long time. But when it comes to a person who has been such a powerful reminder of our very best selves for as long as most Americans can remember, no length of years will ever be quite enough.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com