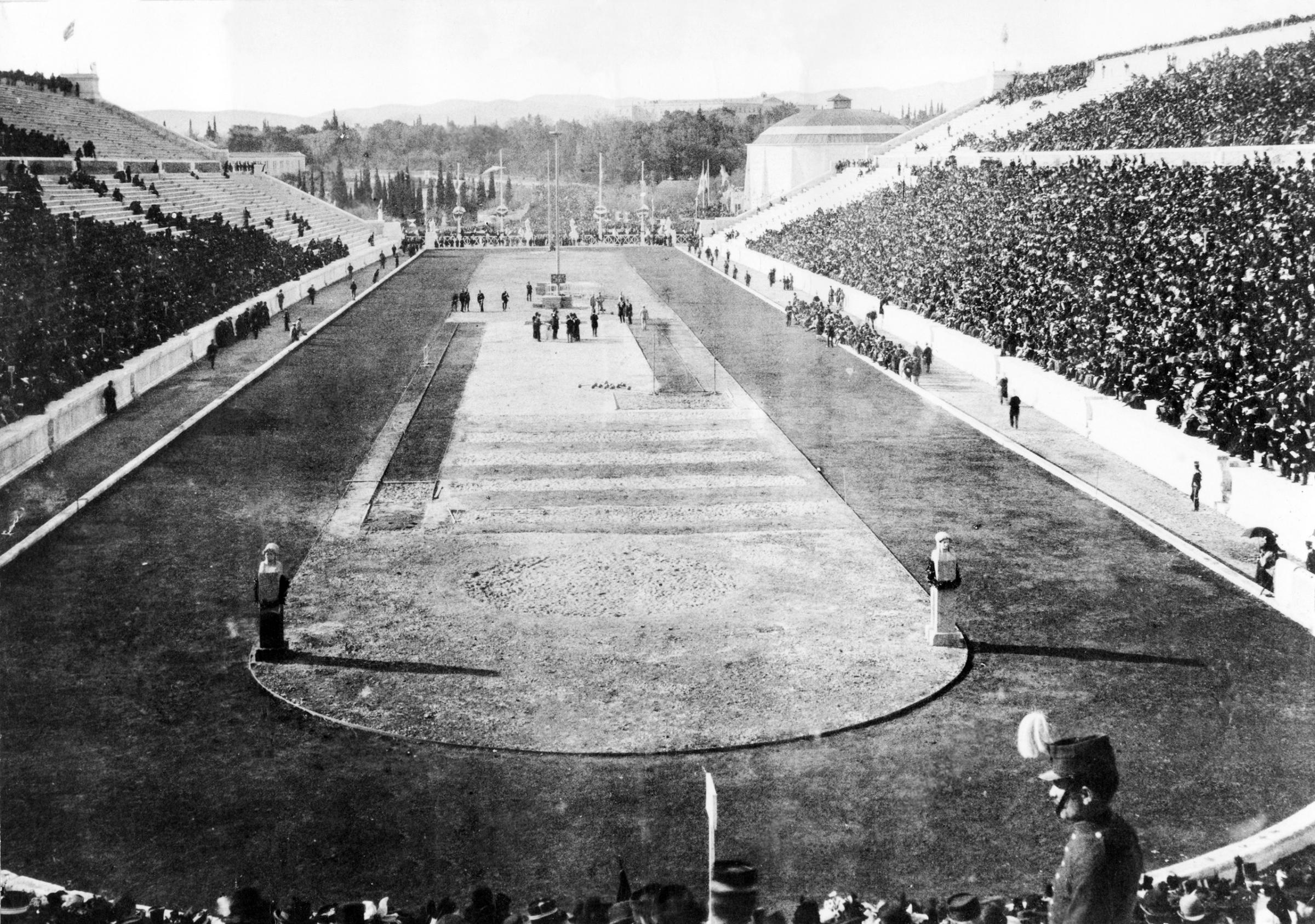

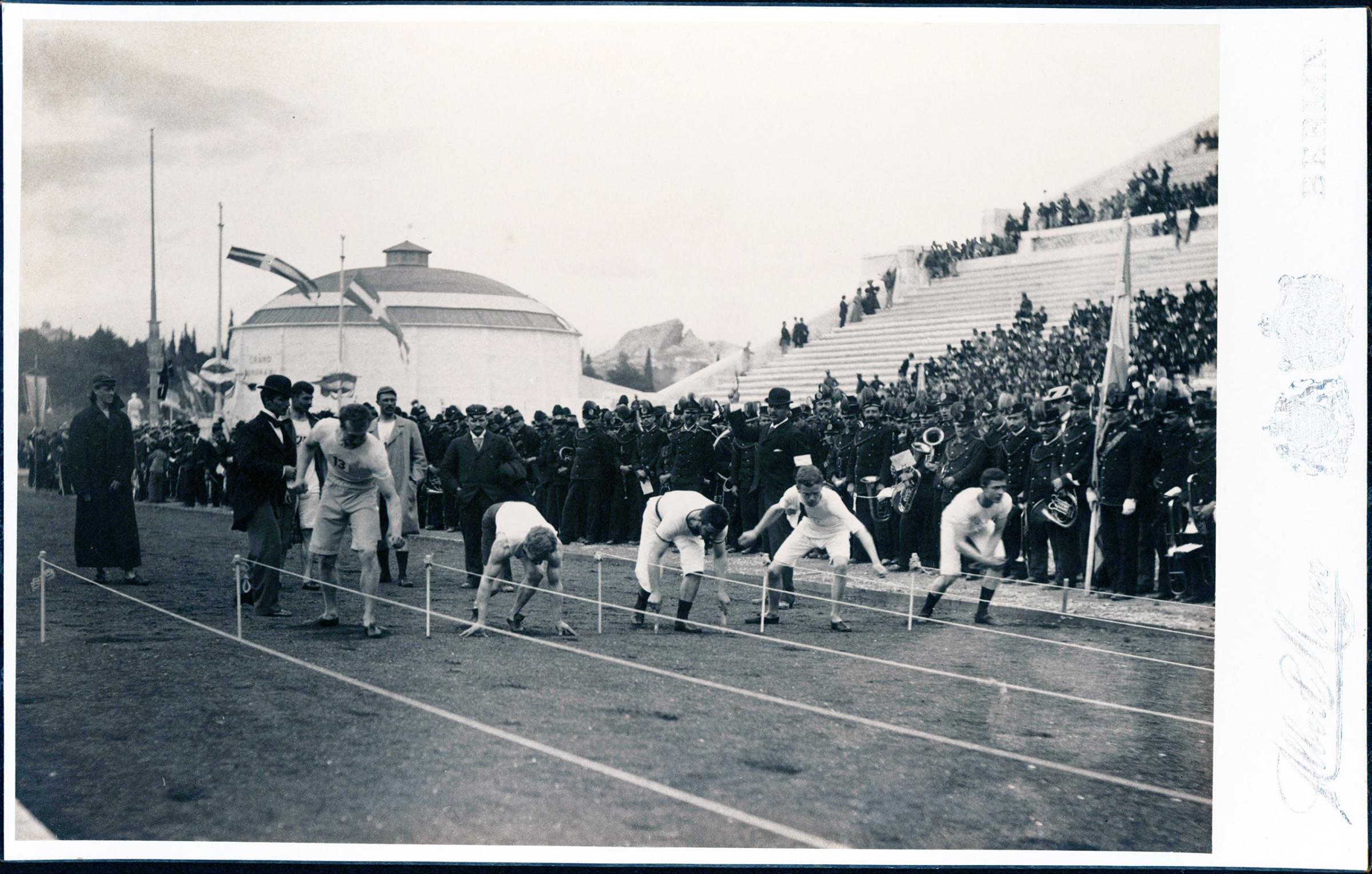

The first Olympics of the modern era began on April 6, 1896, in Athens. It was the first successful attempt to revive the competition that had started in ancient Greece, with centuries having passed since Roman Emperor Theodosius I abolished the event in 393 A.D. because, as part of religious festivals honoring the Greek god Zeus, he believed it promoted pagan worship over Christianity.

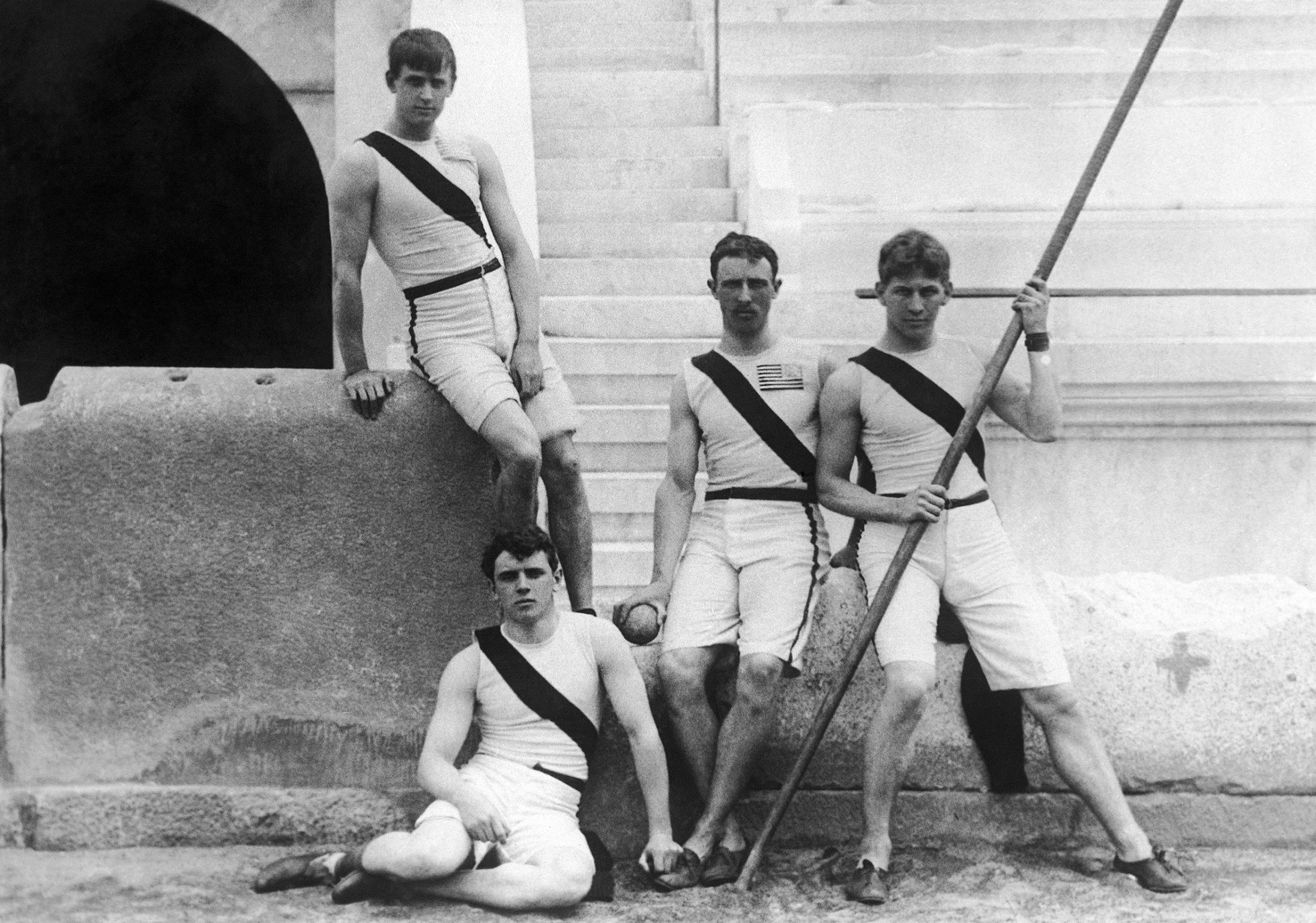

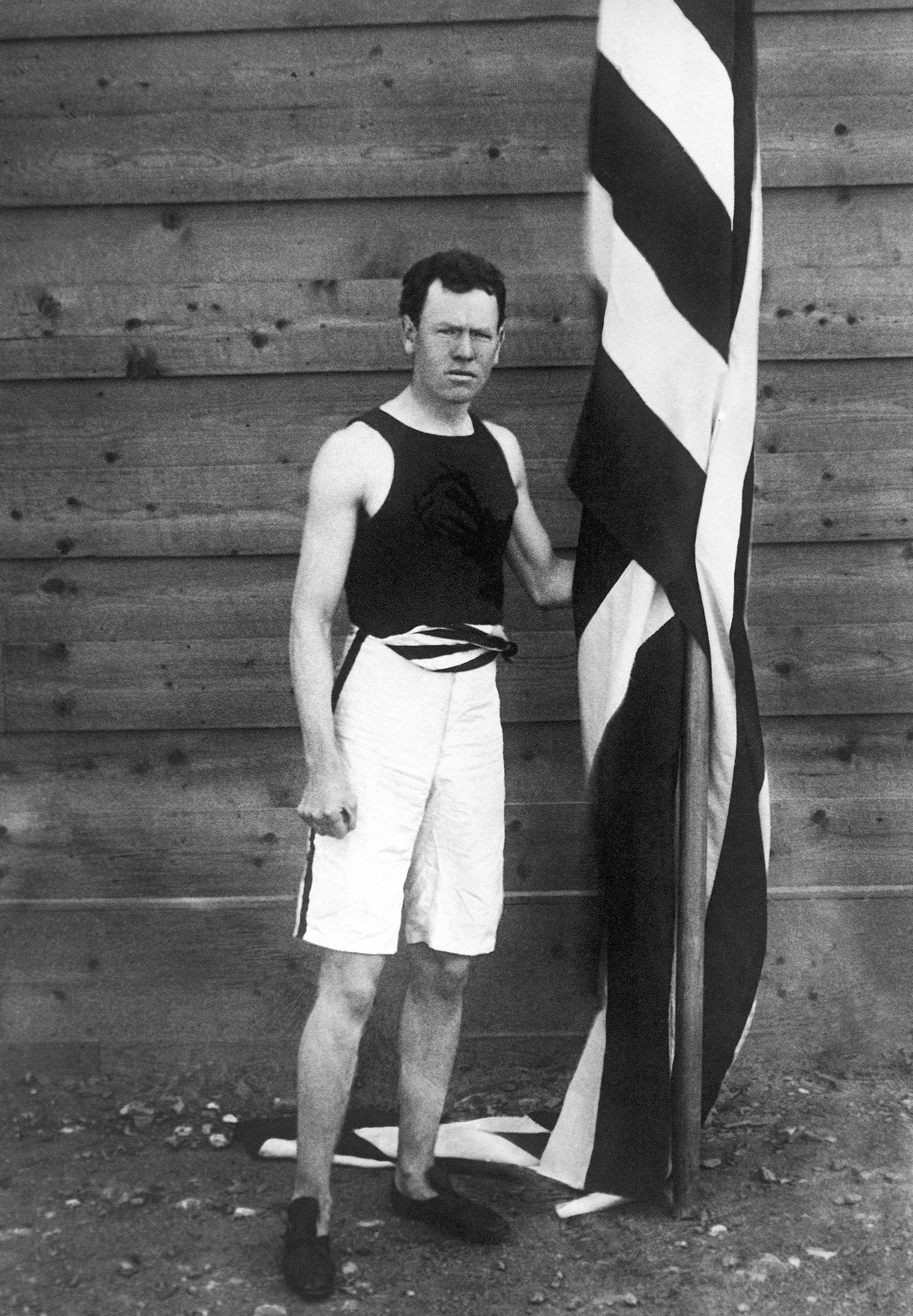

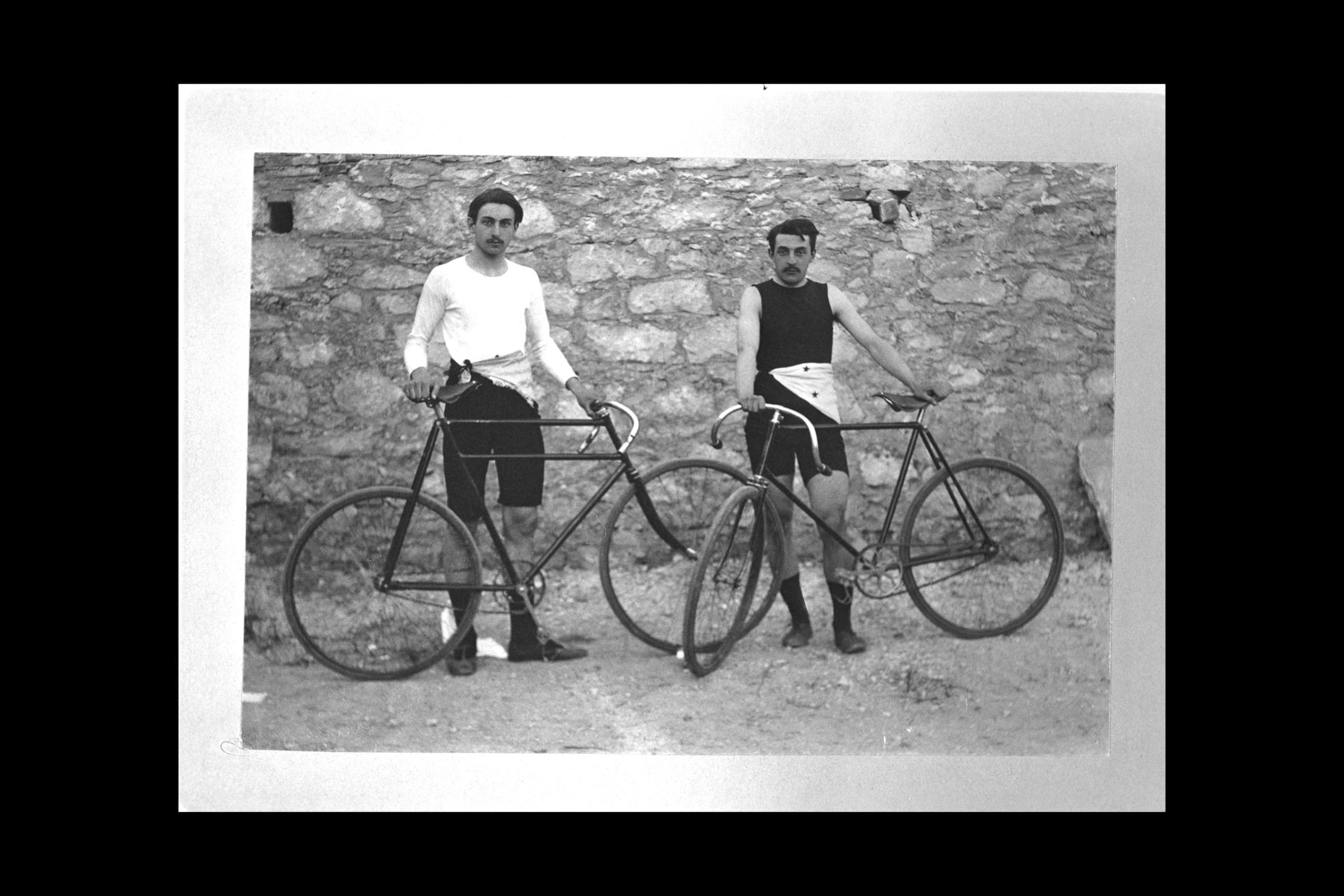

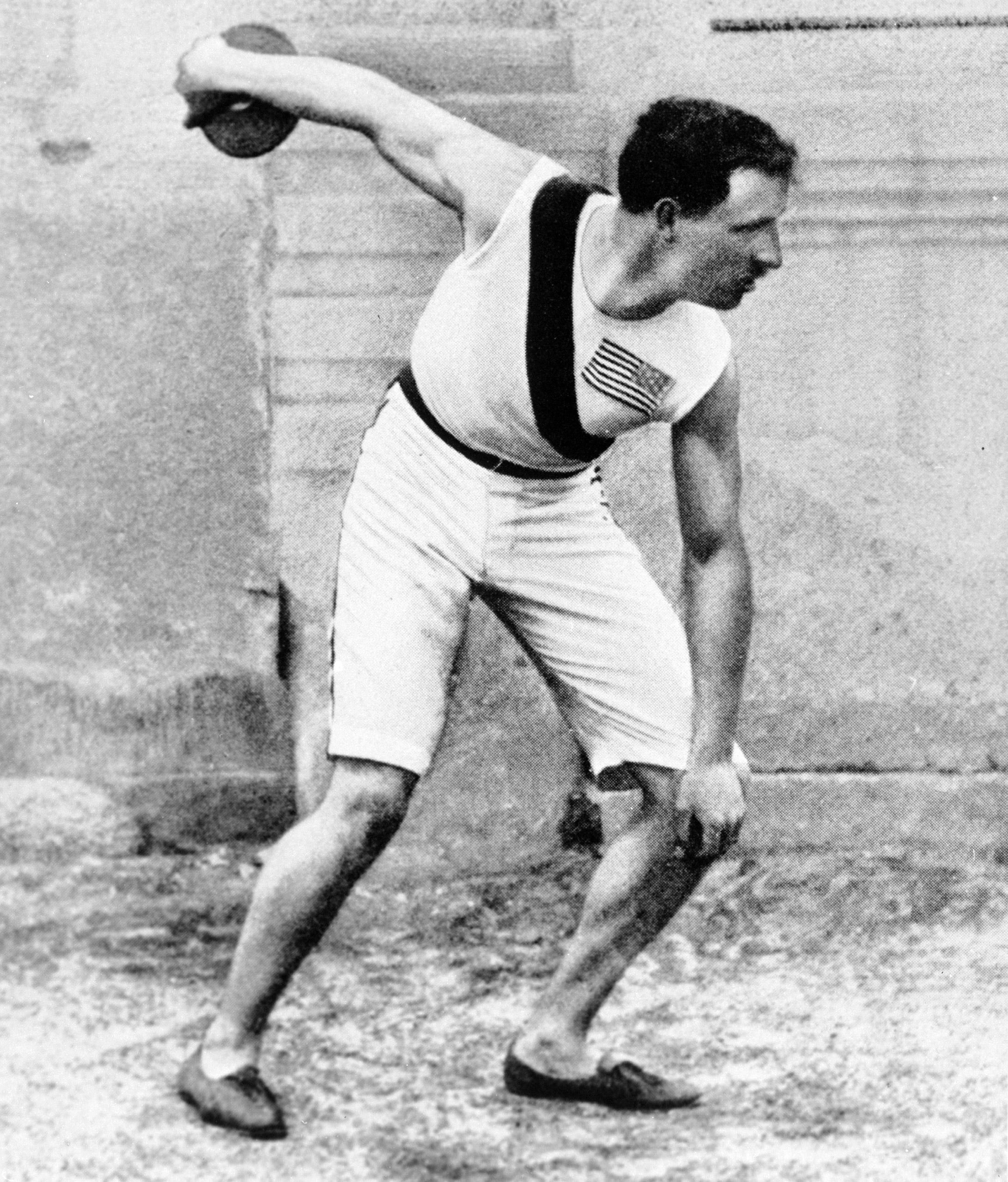

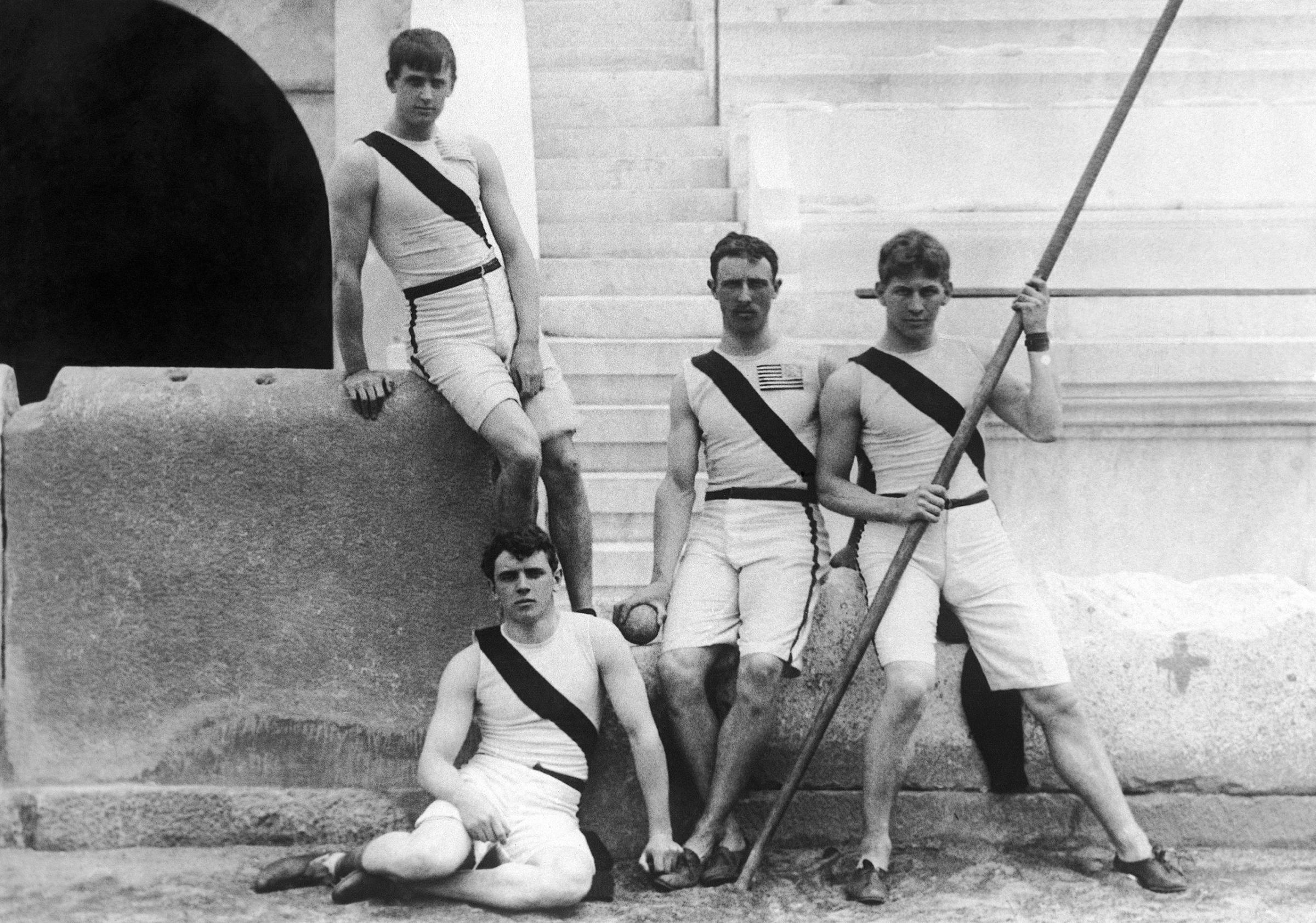

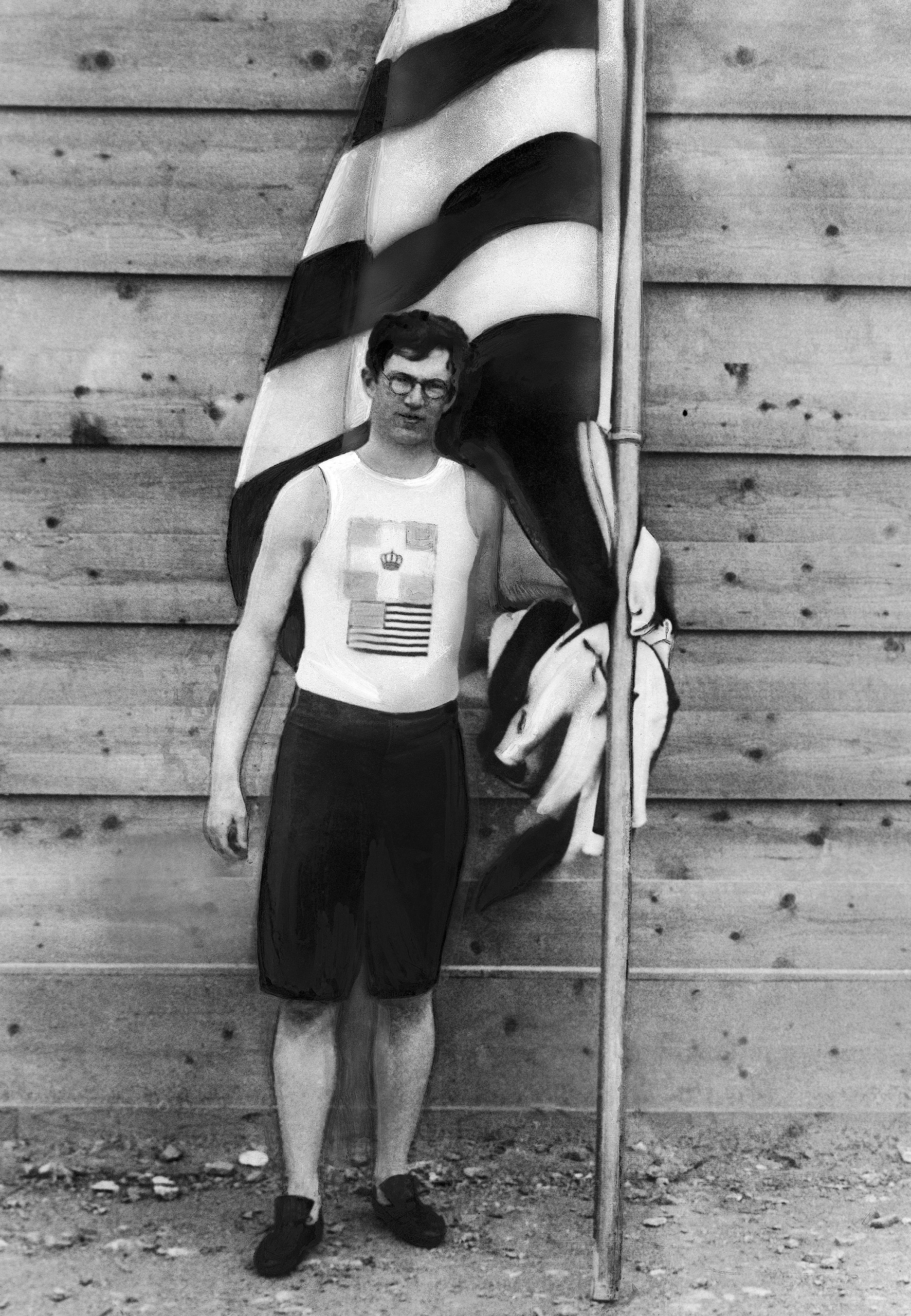

Though 14 nations participated—compared to the more than 200 going to Rio—the majority of athletes represented Greece, Great Britain, Germany and France. The United States sent about a dozen athletes (compared to the roughly 550 athletes representing Team USA in Rio). The above photos show some of the highlights, from James Connolly, a 27-year-old Harvard student who became the first champion of the modern Olympic era when he won the triple jump, to Spyridon Louis of Greece, who became the first marathon champion at the games with a time of 2:58:50. (Though ancient Olympians didn’t run marathons, the race is said to have been included as a nod to the story of the messenger Pheidippides, who ran from Athens to Sparta to ask for help fighting the Persians, as one retelling of the legend goes.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

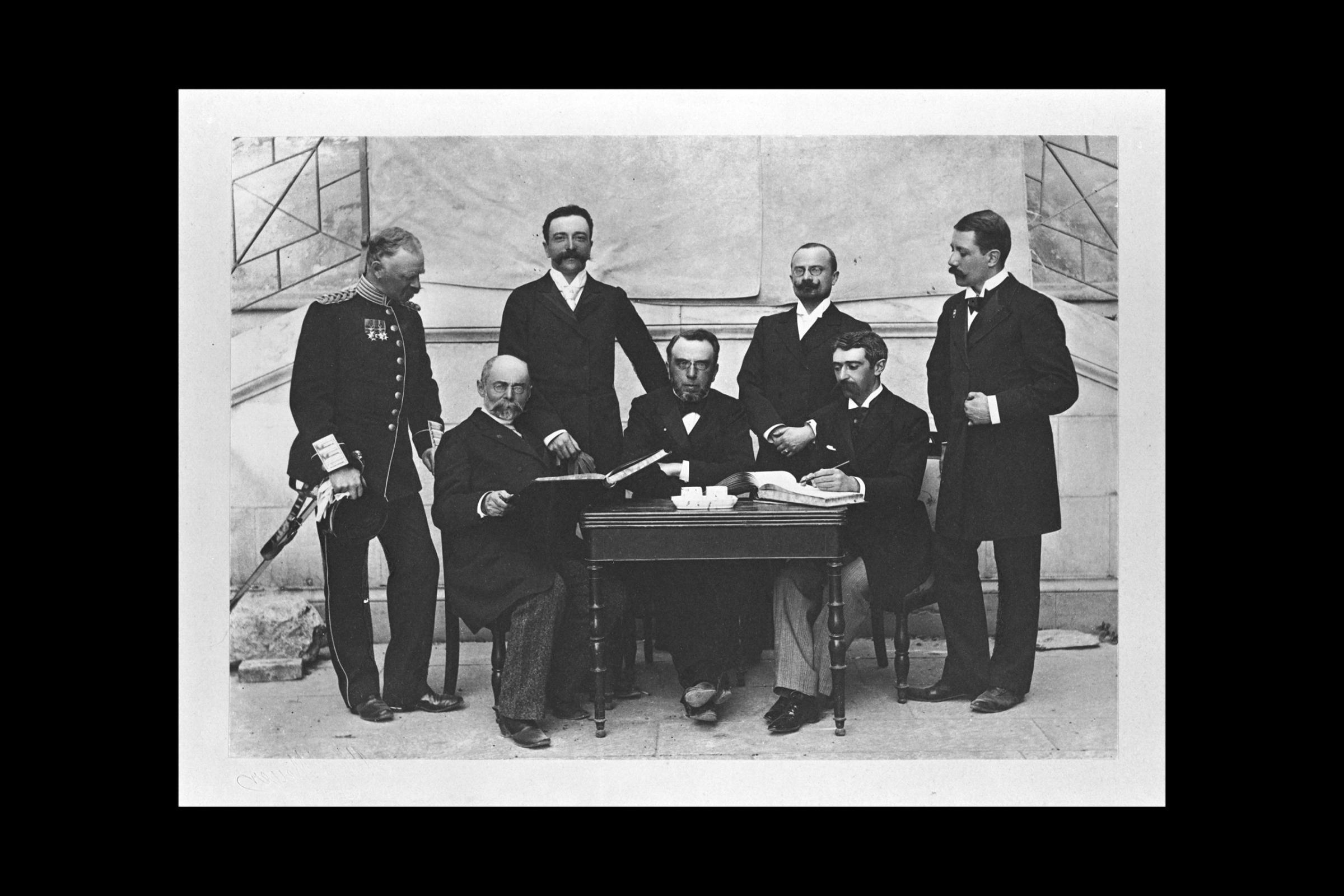

The competition was the brainchild of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat and educator who founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894. His philosophy on sports was influenced by his country’s hugely “humiliating” defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of the 1870s and by a “romanticized” vision of the ancient Greeks that was common among the well-educated at the time, according to Tony Perrottet, author of The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games. “The war got Pierre de Coubertin thinking that French youth need to be much more physically fit, ” he says. “He very much admired the British, who had sports in schools, so he started campaigning to get sports into the curriculum.”

He imagined all wars stopped during the ancient Olympics, so he thought the games would lead to international cooperation and a more peaceful world. And by bringing back the Olympics, he hoped to support the notion of competing for a mere olive wreath, which must mean a love of sport, a view that the Victorian era’s British scholars chose to emphasize over the reality that ancient athletes also received huge cash awards from their home cities, says Perrottet.

These principles — which became known as “amateurism” — ended up favoring those who could afford to train on their own and not be paid, so many athletes in the first modern Olympics came from the world’s finest colleges. TIME once described this notion of amateurism as “a snooty Victorian conceit, installed by the modern Games founder, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, to prevent working-class men from competing against the aristocracy,” and in another article explained that, “Bound up as well in the ideal was a desire to maintain the barriers of class.”

Yet one aspect of Coubertin’s philosophy on sports is something that everyone can relate to, even today, whether they’re athletic or not: “The important thing in life is not the triumph, but the fight; the essential thing is not to have won, but to have fought well.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com