When a truck driver plowed into the throngs of revelers out on the street for Bastille Day in the coastal town of Nice on Thursday night, killing at least 84 people and injuring dozens more, it was the latest in a series of devastating attacks in France. The Charlie Hebdo killings, the mayhem in Paris last November, the stabbing of a police officer in June: the list goes on. Among European countries, France has endured some of the worst assaults by jihadists in recent years, underscoring the country’s ongoing problem with homegrown militancy—and its status as a major target.

The roots of the problem are complex: France has a history of violence in its encounters with the Middle East and North Africa and a domestic Muslim community with long experiences of discrimination and feelings of exclusion from French society. France’s prisons have become a recruiting ground for extremists. And the French radical right is growing in influence, stoking tensions through rhetoric that is often anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim.

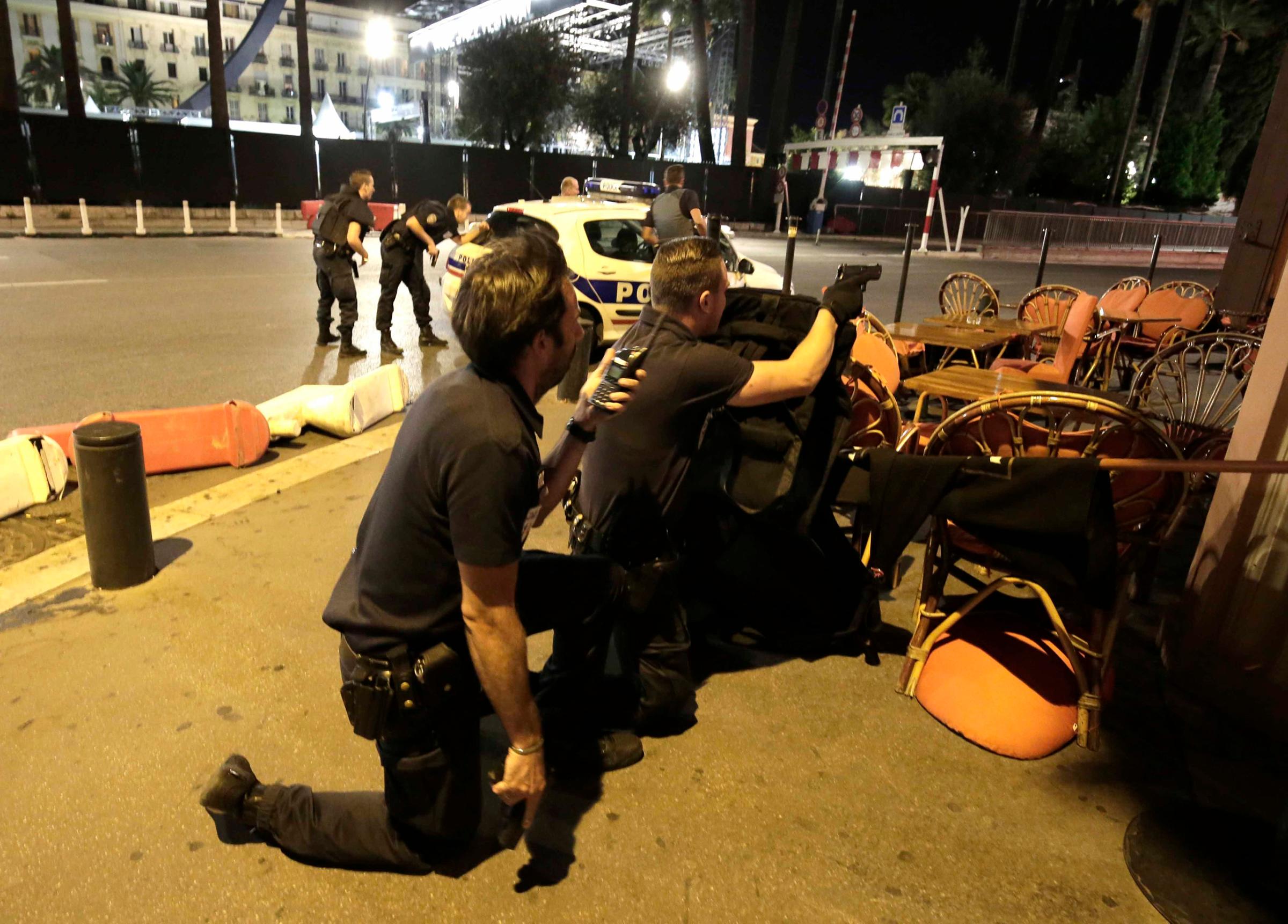

Aftermath of the Truck Attack in France

Read More: Family Mourns American Father and Son Killed in Nice Attack: ‘We Are Heartbroken and In Shock’

Add to that cocktail the recruiting apparatus of the self-proclaimed Islamic State. Some 1,800 people left France to join ISIS and other militant groups in Iraq and Syria as of May 2015, according to the Soufan Group, a security firm based in New York, citing estimates from the French authorities. Another 470 came from another partially Francophone country: Belgium, which has the highest per-capita recruitment rate in Europe. Those are striking numbers, especially when put in context. By comparison, between 600 and 1,000 fighters are estimated to have come from Egypt, the largest country in the Arab world.

Jihadist groups find fertile ground for recruitment in France and Belgium due to those states’ staunch secularism “coupled with a sense of marginalization among immigrant communities, especially those from North Africa,” according to the report from the Soufan Group. “Against this sense of alienation, the propaganda of the Islamic State offers an attractive alternative of belonging, purpose, adventure and respect.” Research by Chris Meserole and Will McCants of the Brookings Institution found that by far the most important variable in predicting how many jihadis a country would produce was whether that people in the country spoke French. Nice itself may have been particularly vulnerable—it has a large Muslim population (several of whom were killed in the attack), and has long had one of France’s most persistent Islamist radicalization problems. The Economist reports that one Nice local, Omar Omsen, was on the radar of local intelligence services, though he was thought to have been killed in Syria last year.

Read More: What We Know About the Driver in the Nice Attack

No group has claimed responsibility for the attack in Nice, and ISIS’ official propaganda arm has not commented on it. That has not stopped individual supporter of both ISIS and al-Qaeda from celebrating the killings in posts on social media and on the encrypted messaging platform Telegram.

The suspect in the Nice has been identified as a 31-year-old French-Tunisian man and resident of Nice named Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel who was known to the police. He had been previously arrested, but had not been known to counterterrorism officials, according to French news reports. ISIS is believed to have an entire branch dedicated to carrying out external attacks, striking far beyond the theater of conflict in Iraq and Syria. The external operations arm has taken a particular interest in Europe and in France in particular, even printing a bomb-making manual in French. This Franco-centrism could be a result of the fact that some of the earliest and most senior members of foreign operations branch have French and Belgian nationals.

Terrorist Attack in Nice, France

In the gun and bomb assault on Paris in November 2015 which left some 130 people dead, ISIS relied on returnee foreign fighters, French and Belgian operatives who had trained with the jihadist group in Syria. But in other cases, would-be attackers need only have cursory contact with jihadi groups, or may find inspiration for acts of violence online. Others, so-called lone wolves, may act on their own. ISIS’ chief spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani issued an explicit appeal for such solo attack in an audio recording released in May.

Read More: What We Know About the Attack in Nice

In France, the profiles of the killers in some recent attacks is somewhere in between the two extremes. Laruossi Abballa, 25, the man who stabbed to death an off-duty police official and his partner in the town of Magnanville in June, had served prison time on a terrorism recruitment charge and swore allegiance to ISIS just before he was killed by police, but there was no evidence he was specially directed by ISIS. Abballa had previously said that a local group of jihadists offered a sense of purpose in an otherwise directionless life that included bouts of unemployment. “I needed recognition,” he told Le Monde.

The roots of France’s jihadi problem lay in its former empire in the Middle East and North Africa, dating back to France’s colonization of countries like Algeria, Tunisia, Syria, and Lebanon. In the 20th century, numerous people from the colonies came to live and work in France, many of them settling in poor enclaves ringing Paris and other cities. In recent decades, as factories closed and jobs became scarce, the sense of social exclusion grew in those communities, especially in the housing projects in the Paris suburbs known as banlieues. The 1995 film La Haine, the story of three men from the housing projects outside France, depicted the desperation of the world of the projects.

The film presaged some of the violence of the years that followed. After two teenagers were killed by electrocution after they hid from police in a high-voltage substation in the Paris suburb Clichy-sous-Bois in 2005, the banlieues erupted in outrage, resulting in weeks of deadly rioting. More than a decade later, observers say that few of the underlying grievances that fueled the riots have been resolved.

Further stoking social tensions, the far right is on the rise in France. The ultranationalist Front National won a plurality of votes in the first round of regional elections last December, but was edged out in the second round as the left voted strategically to keep the far right out of power. Nice is no exception to the right wing trend. Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, the granddaughter of Front National founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, narrowly lost a the race to lead the region Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, where Nice is located. Marine Le Pen, Jean-Marie Le Pen’s daughter and the head of the Front National, was quick to respond to the attacks. “We must not see terror attacks come after another and count more deaths without taking action,” she said in a statement. “The war against the scourge of Islamist fundamentalism has not begun; it’s now urgent to declare it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com