When Google’s 2014 April Fool’s Google Maps-meets-Pokémon mashup teased an official Pokémon Master position at the search giant, it was obvious the company was fooling around.

Except maybe it wasn’t. Maybe, two years later, someone clinched that position after all. Only not at Google, but at an intrepid Google startup that has since gone independent. A San Francisco-based startup dubbed Niantic that takes its name from a fortune-seeking 19th century whaling vessel.

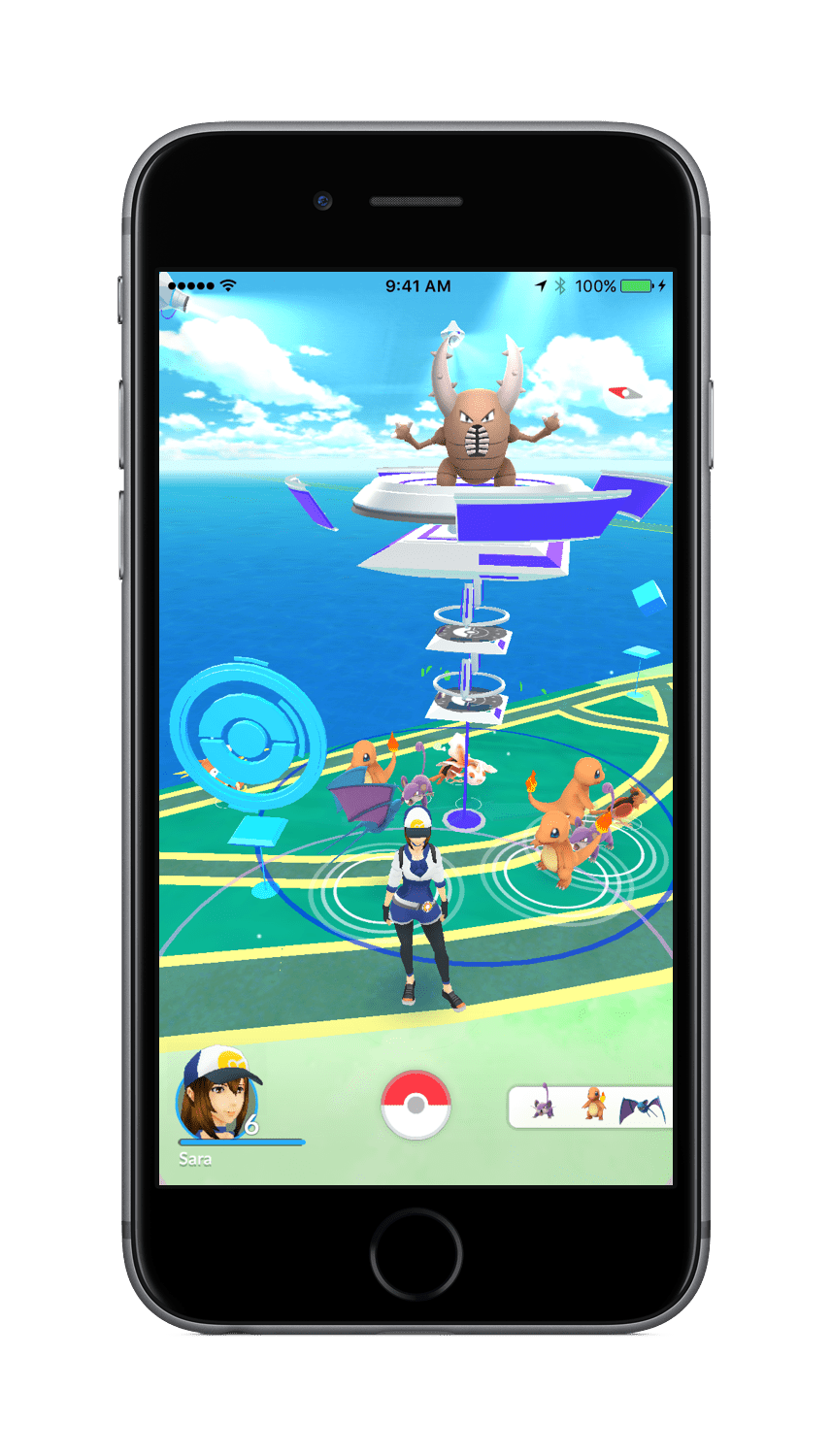

Off the meteoric success of its augmented reality-meets-GPS game Pokémon Go, which launched for iOS and Android on July 6, maybe Niantic founder John Hanke just became the most powerful PokéMaster of all.

TIME spoke with Hanke, who’s been traveling in Japan, to chat about the game’s runaway success, the impact of augmented reality (AR) at this scale, and what he finds interesting about the medium going forward.

TIME: With all the hullabaloo over this thing, I imagine you’re a little world weary at this point.

Hanke: You know, it’s been this adrenaline fueled thing for the past week. I think we are a little weary, but also just can’t believe how amazing it as at the same time. No complaints.

Aside from some of the usual sorts of issues we see with any online game at launch, would you say things are playing out more or less as expected?

We planned for success, and we provisioned our infrastructure for it. But to be honest, we’ve been overwhelmed by the level of interest, by the sheer number of people who want to play and the amount of time they want to play. It definitely surprised us. We thought it would be popular. I mean we didn’t go into it thinking people wouldn’t be excited by it.

But it’s been interesting, this loop of people discovering it, hearing about it through media or social media, playing the game and then bumping into other people playing the game, and then sharing their experiences around that through social media. It’s led to this viral explosion of interest. From our point of view, it’s fantastic. We’re just struggling to keep the infrastructure in place to keep absorbing the number of people who want to play it.

You were involved with Meridian 59, one of the earliest massively multiplayer online (MMO) games. Are the lessons you’ve taken from MMO design the same ones that apply to a game like Pokémon Go?

I think the MMO world — which is itself an outgrowth of the roleplaying Dungeons & Dragons world — you can trace this all back to Gary Gygax and that strange, crazy game that people played with dice and paper back in the 1970s. That’s led us here. Pokémon Go and Ingress, our other game [and the studio’s initial stab at augmented reality], are both very much MMOs. When Ingress was being conceived, I was thinking exactly about Meridian 59, with two main takeaways.

One is that playing against other people is always more interesting than playing against a machine. The challenge and competition of trying to outguess or outmaneuver a real person is infinitely interesting, and it doesn’t get old. And then the other key thing from MMOs was the social coordination, the social organization, which in MMO worlds are called guilds, of course. That’s something we saw with Meridian 59, they spontaneously formed, and we ultimately built features within the product to support the guilds. So there were guild halls you could go to, and if you knew the secret way, you could get in and plan your next adventure with your buddies.

That social organization is exactly the same dynamic here. We saw it in Ingress and we’re seeing it in Pokémon Go, it’s just in the real world. So instead of getting together with a bunch of avatars in a virtual guild hall, you’re getting together with your friends, meeting and going out together, or meeting up with them some place in the city. It just blends in with real life, which makes it infinitely more interesting to me than something that’s occurring only in this virtual space. Because it’s real. Real friendships are forming. You’re out having dinner, having drinks or whatever, and it just feeds and makes our lives better, rather than something that takes us out of that completely.

What do you think about augmented reality having this much impact on real world behavior?

I think there have always been things that people have done socially together. There were bowling clubs, there were softball leagues, there were Lions Clubs. There are all these real world organizations that existed as things people could do together in the community outside of the house. I think a lot of those have atrophied in the digital era.

It’s true, people spend more time indoors, they tend to know their neighbors less, some of those traditional activities have been supplanted by talking to people on Facebook or email, playing video games and watching movies on our big screen TVs. I think it’s really awesome that digital technology has evolved to the point that now we can use it, because it’s mobile, and we can build applications like Pokémon Go that can go and fill some of that void, some of these spaces that have been evacuated.

So I’m not sure Pokémon Go is something new, so much as a new take on something that’s been around for a long time. Which is people wanting things they can do together socially, to give people an excuse to get out and socialize with other people, which at the end of the day makes us feel good.

What do you think about the way this has people behaving in unique ways and on large scales, converging on not just public spaces, but other people’s homes? Do publishers of virtual worlds have new responsibilities when the lines between imaginary and real worlds overlap like this?

I do think people are figuring out the social mores of how to act and what it means. It’s to some extent new territory. To me, it’s an outgrowth of things that have been around for a few years. We all have apps that we use to track our runs, to count our steps, to time our bike rides. I think that’s gone hand-in-glove with people going out and doing more of those activities. Adding a gamified element to it and a social element, I would agree with you it’s new territory, and people are figuring it out.

In terms of our responsibility there, we have guidelines for our players about how to play, about being respectful of the law and of people’s private property and being nice to other users. We try to convey that to our users in every way that we can. The design of the product itself is deliberate in that sense. It’s not a game about beating somebody up. The gameplay itself is friendly, and I think conducive to positive social interaction.

We try to do what we can. The way things have taken off, it’s definitely happened faster than we expected. I don’t know that we have a great deal of control over that. We’ll continue to try to do our best to guide people in the right direction as people’s thinking about this evolves.

Is the distinction here, between the way older MMOs flourished and your point about applying these concepts to the real world, down to how fast this happened?

It’s a very fast ramp-up. In the past decade we’ve literally wired the world together with broadband networks with amazing amounts of capacity. And we’ve socially connected everybody through all the social networks you know and that people use. So if anything, I’d point people in that direction and say that maybe in terms of the speed of things spreading virally, not only within a community or a country, but globally, maybe an outgrowth of that platform, of that infrastructure that’s been gradually put in place over the past decade, now it’s there, and everybody is wired together, with completely and robustly fantastic connectivity. So yes, things like this can spread very, very quickly.

Given the extent Pokémon Go operates in the public space, and both the public and media’s tendency to focus on outliers or novel negatives, do augmented reality publishers have an obligation to react if statistically meaningful negatives start to occur?

From our perspective, this is not an overnight success. We started working on this problem space in 2011, we launched Ingress in 2012, we’re now past our third anniversary and [Ingress is] played in over 200 countries. We have events every month in cities around the world. I’m here in Japan because we’ll have one this Saturday, and there will be over 10,000 people at that event.

We’ve really honed the dynamics for this type of game, the dynamics that we built Pokémon Go around through Ingress. We’ve watched the community develop. We know the things that are positive about the game, that we wanted to carry over into Pokémon Go, the movement, and physical exercises, discovering new places, the social aspect of it. The game was built around those cornerstones.

Are we going to have to have a cultural moment, where we’re coming to grips with what it means to interface with imaginary worlds layered on top of reality?

I think we’re having it. [Laughs] You were asking about the media. There have been people who’ve looked at outlier cases of Ingress. At the end of the day, the community always has carried that story for us. When journalists reach out to the community and ask “Why are you playing this game? Why are you doing this? Is it weird that people are out in the middle of the night?” The response is, “It’s amazing, it’s changed my life. I’ve met so many new people, I’m seeing the world in a completely different way. I’m walking three miles a day and I was housebound and watching TV all day before I started playing this game.” It’s positive story after story.

If you go through the press archives for Ingress, which a lot of people didn’t know about, it was a much more niche product than Pokémon Go. But you’ll see that theme repeated over and over. Whenever I see people pick on a negative outlier, it is what it is. Those things are going to occur. The positive stories are pouring out from people in the community, completely of their own accord. We don’t have to be the public relations platform for that, you can just go read it online. That’s what we focus on, and I feel confident that will carry us through any of the negative stuff.

But it is sparking a really interesting dialogue out there, to your point about us having a moment. Yeah, maybe it’s going to be a bit before we’re comfortable with what an augmented reality future can do for us. But frankly it’s already a lot of really positive things, at the end of the day, and that’s a good thing.

Thinking about the future and what’s next for Niantic, what sort of augmented reality ideas do you find most interesting?

The unique thing about AR versus [virtual reality, or VR] is that AR enhances the things that we do as human beings out in the real physical world. It’s not something that completely replaces them with a fantasy experience. You see that with Pokemon Go. There’s of course this fantastical Pokémon element, but really it’s enhancing your experience of going out for walk or doing something with friends.

I think that’s the potential of AR if you want to contrast it with VR. I think AR is something that can be with us all the time, that we can use during the day and in everything, from commerce to entertainment to social interactions. Even dating. Those are all things where AR experiences are going to evolve from the ones we have on mobile phones today, just to be more integrated with our behaviors, if you will, and make the things that we do as human beings better.

That’s not a direct answer to your question but I think it’s those types of applications that make the things we already do more interesting, more entertaining, more efficient, that’s the potential AR has for us. And it’s a big one. The opportunities are huge.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com