This summer marks 202 years since a force of American soldiers and volunteers embarked on the nation’s first war on terror. It did not turn out well. Today it reads like a cautionary tale.

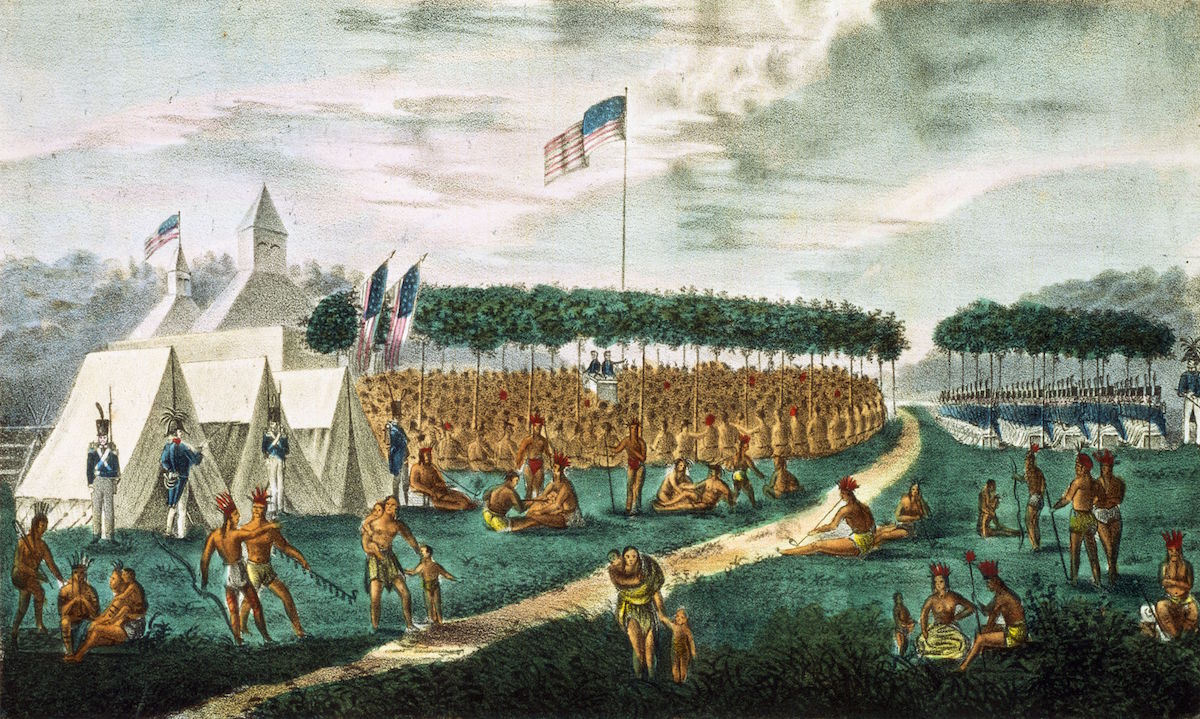

On May 1, 1814, an ad hoc flotilla of five armed keelboats and 200 soldiers headed up the Mississippi River from St. Louis. Their “terrorist” targets—the word was already in use then—were Native Americans. The man leading this audacious American enterprise to crush them was none other than William Clark, the recent hero and co-leader of the Lewis and Clark expedition. The War of 1812, then raging along the Eastern seaboard, was about to open a Western frontier.

Clark, who had been appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory, had been outraged by a series of deadly attacks against American settlers. In his view, they were calculated and coordinated attacks, conducted with the support of a foreign power—British Canada. The mastermind was thought to be the Hudson Bay Company fur trader Robert Dickson, whom Clark blamed for inciting the northern Indian tribes along the American frontier.

Atrocity stories fanned the flames of revenge. In April, two men were shot and mutilated at Boonslick, Mo., and a Captain Cooper was killed at his hearth by an Indian who poked a hole through a log wall and fired a shot into the house. “Those savage bands between Lake Michigan & the Mississippi, we must Consider as our Enemies,” Clark concluded.

But what Clark and his countrymen rarely mentioned was that settlers usually came under attack only after moving into Indian lands they did not own. Only a decade earlier, William Henry Harrison had signed a treaty that had appropriated millions of acres of Sauk land. When 400 American families settled north of the Missouri on land claimed by the Sauks and Iowas, Clark found an imaginative solution. He proposed not removing the trespassers but rather redrawing the proposed boundaries of St. Charles County “to include this rich and flourishing settlement, and some of the best lands in the Territory.”

In February, as the attacks continued, the anxious residents of St. Louis called a town meeting to protest the lack of defense from the federal government. Emboldened by the news of Andrew Jackson’s near-massacre of the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend, Ala., the Missouri Gazette was thundering, “The BLOOD of our citizens cry aloud for VENGEANCE. The general cry is let the north as well as the south be JACKSONIZED!!!”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Clark had long argued for a military strike up the Mississippi into the heart of Dickson’s trading network. Acting on his own authority, without approval from Washington, Clark recruited 150 men to serve as a short-term militia, with the goal of taking possession of Prairie du Chien, a strategic post on the Upper Mississippi. The men would be paid $20 a month directly, and ironically, out of the Indian aid fund.

Clark’s stated goal was to “flusterate the plans of Mr. Dickson.” Secretary of War Armstrong belatedly approved the expense but remained skeptical. “I cannot believe in the wisdom of establishing a post 600 miles in the enemy’s country,” Secretary of War Armstrong noted on the letter he received from Clark. “Once established it must be supported & at an enormous expence.”

On June 2, Clark and his troops arrived at Prairie du Chien to find it virtually deserted, as Dickson and his trooops had learned of his expedition and departed for the Canadian stronghold of Michilimackinac three weeks earlier.

And yet the taking of Prairie du Chien was not bloodless. The British complained of “horrible cruelties” by “these relentless Assassins,” and recorded allegations that Clark had “captured eight Indians of the Winnebago Nation,” given them food to win their trust, and then “murdered seven in bold blood” while they were eating. Meanwhile, the Americans announced that Dickson had hired a local warrior to assassinate Clark. They also confiscated several trunks of Dickson’s records and announced that the papers proved that the Scotsman was indeed a “hair-buyer,” who had rewarded an Indian bringing in one scalp with “5 carrots of tobacco; 6 lbs. Powder; 6lb. Ball.”

Clark located a commanding site overlooking the village and set his men to work building a triangular fortification what would be named Fort Shelby. A day later, he was heading back downriver, leaving behind two gunboats and a small garrison of 135 soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Joseph Perkins.

On June 13 Clark arrived triumphantly in St. Louis with news of “the fortunate results of that hazardous enterprise.” With the new fort erected, and his soldiers “anxious for a visit from Dickson and his red troops,” Clark and his friends gathered for a celebratory banquet at William Christy’s Missouri Hotel, where they raised toasts to “the late expedition has cleansed [Prairie du Chien] of spies and traitors.”

It did not take long for the American soldiers at Prairie du Chien to receive a visit from Dickson’s “red troops.” In the morning of July 17, they were startled to see a combined force of at least 650 Indians, British regulars and Michigan Fencibles (a militia of Canadian trappers) assemble in the prairie three miles away. Dickson had raised what amounted to a private army to retake Fort Shelby. The siege lasted 54 hours before the American forces surrendered, in exchange for safe passage back to St. Louis.

What had started as toasts and triumph had ended in a fiasco.

Landon Jones is the author of William Clark and the Shaping of the West (Nebraska).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com