If you’d googled the name Mark Hughes on Thursday morning, you would’ve gotten pages about a Welsh former professional soccer player turned coach. By Thursday evening, in the aftermath of a horrific shooting at a Black Lives Matter rally in Dallas that left five police officers dead and another seven wounded, you would’ve gotten the photo and name of a gun-toting man suspected of killing cops.

The problem is: the man in that image released by the Dallas Police Department Thursday evening was at that moment joking around with cops as he helped safely evacuate panicked rally attendees.

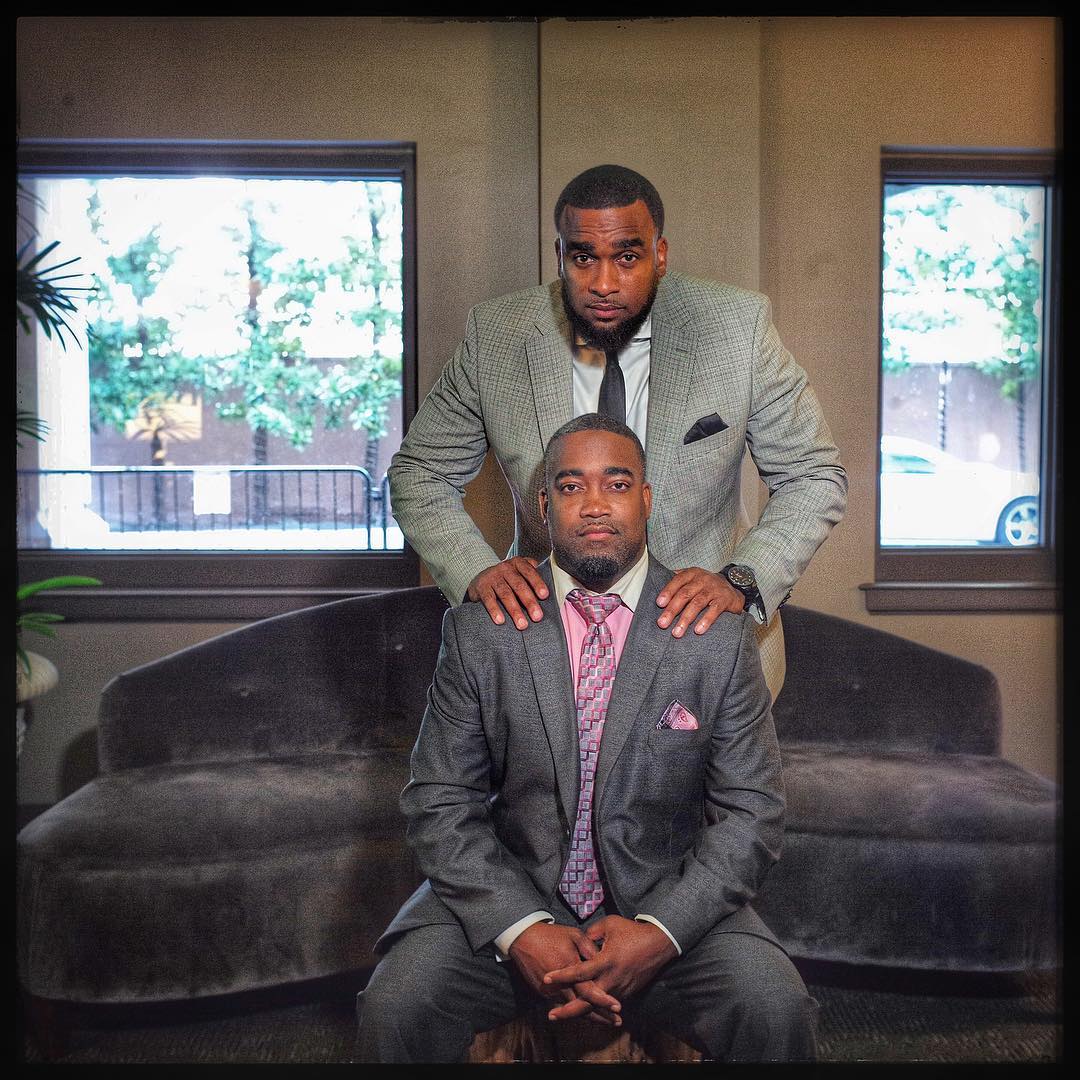

The tale of Mark Hughes and his brother Corey is a story of everything that is wrong with race relations and policing in America today, except that this tale has a marginally happier ending in that no one actually died. Hughes says he’s lucky to have left police custody alive, though without his rifle or the shirt off his back. But, he notes wearily—by Friday afternoon he still hadn’t slept—he must now live fearing for his life and the safety of his family; both Hughes brothers have received “hundreds” of death threats, presumably from people who believed or still believe that he is a cop killer.

“Mark Hughes of yesterday is not the same Mark Hughes of today,” he tells TIME, sitting in his lawyer’s offices a couple of blocks from the crime scene. “When I was walking out of the police station, I saw on big screen TV—on CNN, I think—I saw my face on there. I couldn’t believe it. I was angry for the simple fact that I hadn’t done anything wrong. I was just down there to clear my name.”

Thursday had started with anger, and a sense of incredulity—but the kind held at a distance, on behalf of someone else. Mark, 34, and Corey, 39, had been talking about the four killings of black men by police officers across the country in as many days. They wanted to do something about it. Corey had been asked to be on the board of the Next Generation Action Network. The group is unaffiliated with Black Lives Matter but it has some of the same threads: it’s a loose collection of minority voices, often unheard by authorities, seeking justice and recognition. NGAN had planned an impromptu march in downtown Dallas to show solidarity with those killed and Corey was asked to speak.

Mark decided to accompany his brother and to make a point, he decided to come with his rifle. In June, Donald Trump had held a rally in Dallas and several Caucasian men had come openly carrying rifles—in Texas anyone who has legally purchased a rifle can openly carry it. Mark thought he’d make the same point with his AR-15. So, wearing a camouflage shirt and toting his gun, Mark went to listen to Corey speak about how the lives of black men were being reduced to hashtags and Internet memes.

The brothers were about a block away when the shooting began. They ran for cover and then Corey advised Mark to hand over his weapon to the police lest they think he might have been involved. Mark did so and the two helped the police evacuate the area. Little did they know that someone had snapped a photo of Mark earlier that evening and handed it to the police as a potential suspect. The police posted the photo on social media with an appeal: “This is one of our suspects. Please help us find him!”

Mark had left to go search for his car by the time he’d realized the police were mounting a massive manhunt for him. His first reaction: fear. He immediately took off his shirt. He skirted a mob of policemen, afraid of how a group might react, and found a couple of solitary cops whom he approached. They cuffed him and sent him to central booking.

Meanwhile, Corey’s phone had died but when he’d finally gotten it charged his heart dropped. Mark’s face was plastered everywhere. “I thought my brother was going to become a hashtag,” he says. “An enraged police force—hearing chatter [of] multiple shooters, some of their own had fallen—and Mark became the face of their rage. My brother had no idea that he was now a domestic terrorist.”

Corey went to the police to explain Mark’s innocence. He eventually found his brother, who police had realized had nothing to do with the attack, arguing with officers about his gun. Corey convinced Mark to leave the weapon. “We know we’ve done nothing wrong, but there are photos of us all over social media,” Corey says. “I didn’t think it would be wise to walk out there with a gun.”

So, the pair left the gun—and Mark’s shirt, which the police refused to give back—and walked away. They were never read their Miranda rights, though both were detained. They were interrogated even after both invoked the right to counsel. They walked away to jeers from policemen. And when they asked that the police take down the tweet, or at least correct it, they were declined.

Ultimately, the police did send out a tweet saying the “suspect” had been questioned and released and by late Friday, they had taken down Mark’s image, though it remains in a video on the Dallas Police Department’s website. And while a tweet started the whole mess, Mark’s friends used Twitter to help correct the record quickly.

Now when you google Mark Hughes, headlines about how he was falsely accused are mostly what come up. But that is cold comfort for the brothers who, with their young children, are essentially in hiding. The death threats are still coming, some of them with google maps of their homes ominously attached. Both men are entrepreneurs whose businesses, they say, are not only suffering but have come to a grinding halt because of this. And still, they haven’t heard a word from the Dallas police.

They would like Mark’s gun and shirt back and they would like an apology. When asked if they’d want protection, both shudder: “I couldn’t trust the police again,” Corey says.

Dallas police did not respond to requests for comment on Friday.

But all of this hasn’t deterred them: they plan to continue attending rallies. And Mark still plans to bring his gun, when he gets it back. “If we stop going to rallies and we stop bearing arms for fear that thing will happen to us, we’re doing our ancestors an injustice—it means we are giving in to intimidation, threats,” Mark says. “The laws that were passed would not be there for us if we let it go and don’t exercise them.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com