Omega-3s are the fats that made fish famous. Really famous: fish oil is now the most popular natural product in America among U.S. adults—8% of whom take it—and children. Our bodies need these essential unsaturated fats but can’t produce them, so we rely on sources like seafood or supplements to get enough.

But as omega-3s have surged in popularity, they’ve also become the subjects of an unending stream of studies, with experts trying to figure out if there is enough science to support their hyped up health benefits. Their conclusions so far have been surprisingly uneven, and that’s especially true when it comes to heart health.

For years, the studies mostly supported the idea that omega-3s are beneficial to the heart. But some recent research has a more mixed message. “There’s been a lot of confusion, because lately some studies have shown that omega-3 doesn’t seem to help,” says Dr. James O’Keefe, chief of preventive cardiology at Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City.

Ever since the 1970s, when researchers found that Inuits in Greenland, who kept a diet rich in fish, had heart attacks much less often than Americans, researchers have conducted huge epidemiological studies trying to figure out if eating fish, or taking fish oil in a pill builds a healthier heart. The thinking goes that omega-3s build up the cell membranes— “the little skin around each of the ten trillion cells that make up each one of us,” says O’Keefe. Omega-3s, then, keep those membranes soft and supple and help the cells work well to transmit information from other cells, particularly in the electrically sensitive areas of the heart and the brain (another area shown to respond well to omega-3s). Omega-3s have also been shown to reduce inflammation, which is one of the common denominators in a lot of common diseases, like diabetes, dementia, heart disease, macular degeneration and arthritis, O’Keefe says.

So what’s the final word on omegas?

Recently, a large study led by researchers at Tufts University and published in JAMA Internal Medicine added to the weight of evidence in favor of the fatty acids for heart health. The researchers looked at levels of omega-3s in the blood and tissue of 45,637 healthy people, using data from 19 prospective and retrospective studies, to see if there was a connection to coronary heart disease. They didn’t find a link between omega-3s and heart attacks in general, but they did find that people who had diets rich in fish-derived omega-3s had a lower risk of fatal heart attacks. How impressive the association was depended on their omega-3 consumption. For every extra serving or so of fish a week, they saw about a 10% reduction in risk, and people who ate the most fish had about a 24% lower risk of fatal heart attack than people who ate the least.

“Evidence from experimental models and animal studies show that a major effect of these omega-3 fatty acids is to stabilize heart membranes,” says Liana Del Gobbo, lead author of the study who is now a research fellow at Stanford University. Stable heart membranes means the heart is less likely to go into life-threatening dangerous rhythms, adds O’Keefe (who was not involved with the study).

This kind of study can’t determine cause and effect, so it’s impossible to know for sure whether fish was responsible for the link, says Dr. Steven Nissen, chairman of Cleveland Clinic’s department of cardiovascular medicine. “Levels of omega 3 in the blood are a marker for having healthy behaviors,” he says, adding that omega-3s may not be causing the benefit. That’s the problem with many of the large studies around omega-3s, he says. “Epidemiological studies are not considered to be definitive scientific evidence. They really do not contribute to making decisions about how to care for patients—to do that we need randomized controlled clinical trials.” Several of these have been done using fish oil supplements, but the recent ones haven’t produced a clear picture.

O’Keefe says that one reason for the mixed message could be that people who participate in omega-3 supplement studies may be more aware of the fatty acids’ benefits—and therefore more likely to eat fish—than the general population of Americans who are woefully deficient. That might be why comparisons between the two groups often aren’t impressive. Del Gobbo agrees. “If you’re giving fish oil to people who are already eating a lot of fish, I wouldn’t expect the effects to be large,” she says.

There’s not yet enough evidence to convince Nissen that omega-3s have important effects on the heart; he’s currently conducting a randomized controlled trial to test a pharmaceutical-grade omega-3 pill and expects to have results within the next four years.

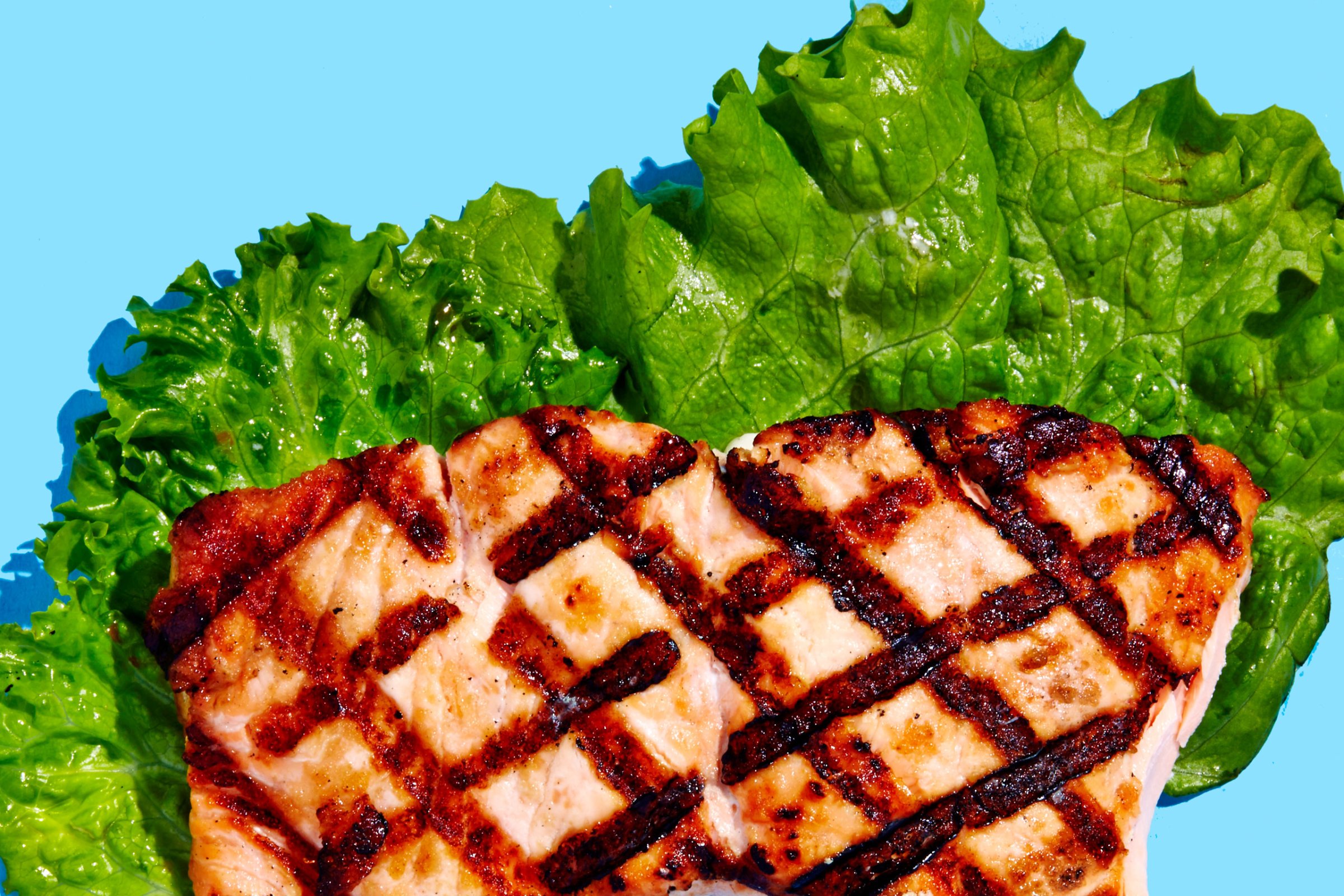

But what’s not up for debate is that fish is healthy. Eating two to three servings of fatty oily fish, like salmon or sardines, each week is enough to get the omega-3s you need, says Del Gobbo.

As a nation, we’re a long way from that goal. Roughly half of Americans eat fish only occasionally or not at all. As a result, our cell membranes look different, O’Keefe says. “In countries that have a high intake of omega-3 like Japan, their average omega-3 level is about 8% in their cell membranes. In America, it’s about half that. And sure enough, the Japanese have less than half of the heart disease deaths that we have.”

The picture on omega-3s and heart health isn’t crystal clear yet. But there’s plenty of evidence in favor of a salmon fillet for dinner tonight.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mandy Oaklander at mandy.oaklander@time.com