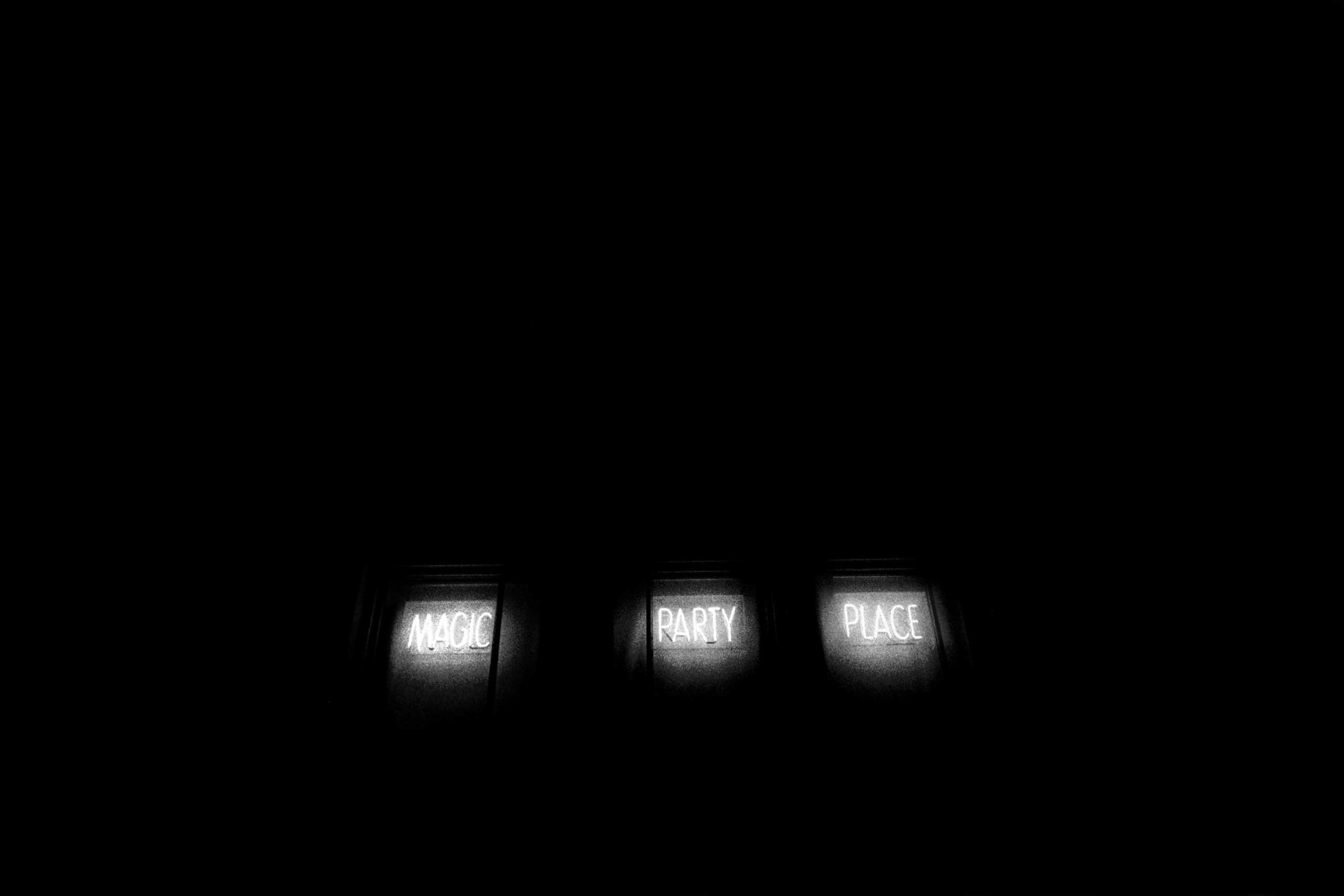

Basildon, built after World War II, is a town of 100,000 inhabitants just 25 miles outside of London. “As a constructed community, the town is statistically close to the national average,” says documentary photographer CJ Clarke, who grew up in Basildon and chose to document it for his first photobook, Magic Party Place. “[Basildon] is the perfect paradigm through which to explore the state of the nation,” he says, days after 51.9% of British voters chose to leave the European Union.

Clarke speaks to TIME LightBox about the creative process behind Magic Party Place.

Olivier Laurent: What’s the genesis of this work?

CJ Clarke: The beginnings of this work lie very much in my own origins as a native son of Basildon in Essex, the town I documented for the book. When I was 18, I left for university and never thought I would come back but, because of this project, I returned and confronted it as a stranger. On a personal level, Magic Party Place was a process through which I reacquainted myself with the town; I got to know it with an intimacy and depth that I didn’t have when I was a teenager growing up there.

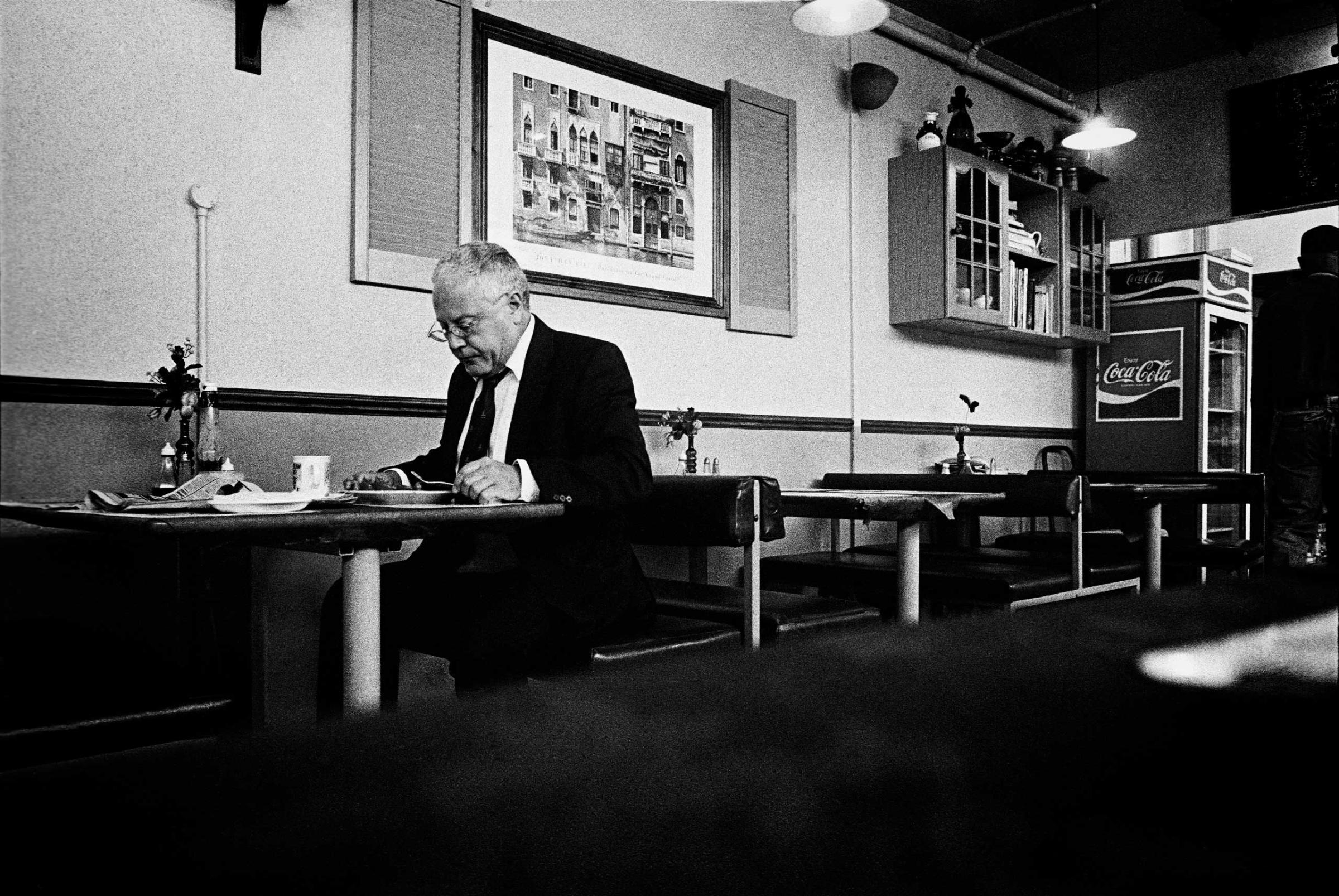

I documented Basildon though, not because it was my home town, but because it happens to be one of the most averages places in the U.K. It is a new town built after World War II; it is culturally homogenous with many people originally moving from the same part of London in the late 1940s and in the 1950s. It is almost 90% white and, in the most recent census, most people described themselves as English, not British. It’s no surprise therefore that 68.6% of people voted to leave the E.U. in the recent referendum.

Specifically though, the reason that this work exists at all is pretty much down to the great photojournalist Judah Passow. I was put in touch with him in 2005 when I was a student; I was casting around for final project stories – like many my age I was politicized by the war in Iraq, I thought I would be a photographer and cover the Middle East, a project on Palestine and then I met Judah… He didn’t know me and kindly agreed to meet me for coffee. He was kind and generous with his advice and we were chatting and I mentioned my fascination with my home town and that it was statistically average and he jumped and said, “You gotta do this story!” I said “Really? You think?” and he said “Yeah! Are you kidding me, you gotta do this!”

Olivier Laurent: When did it become a book in your mind?

CJ Clarke: From almost the very beginning, I conceived of this project as a book. The first iterations of it were book dummies and over the ten years that I have been working on this project I have produced some seven or eight different dummies. They have been rudimentary affairs, nothing fancy, but each one had been a refinement over the one that came before; a subtle change of sequence or the interplay of the accompanying text. It was really just a matter of when rather than if. Throughout this process I have relied on a core group of friends and colleagues whose opinions I can react against to keep me on, so to speak, ‘the straight and narrow.’ It is easy to forget that you are producing a piece of mass communication and to get lost in your own narrative.

Olivier Laurent: Once you’ve decided to make a book, what was the process to make it happen?

CJ Clarke: For me, the process was very straightforward. The first designer I approached, Teun van der Heijden, said he wanted to work on the project as did the first publisher, Kehrer Verlag. It means a great deal to me to have one of the leading book designers and one of the leading photo book publishers involved in this project. It really couldn’t have been done without them and their keen collaboration.

From that point on, the process took just under a year. Teun and I met several times to work on the book and refine the concept, which Teun developed. In those initial phases I was happy to hand over the edit to him. I have very strong opinions about the work and how it should look but in any good, collaborative process you have to take a step back and see how other people relate to the material. This is a way of understanding how an audience might relate, a way of testing my own thinking about the images, my narrative and what contextual material was required. I’ve been working on this for ten years, so, at some point, no matter how rigorous my own vision of the work, or my own ability to edit the images, you need other opinions to which you can react.

Olivier Laurent: Going through the whole process of putting the book together, what have you learned (both on the bookmaking process but also on your own work)?

CJ Clarke: Bookmaking is a collaborative process, which I particularly enjoy. It is similar to when I am directing a film; you have to work with a diverse range of people, all with different skills and ideas, all feeding in and working towards a common goal. It is a fantastic process.

All powerful stories are personal but that means nothing if you cannot find a way to communicate what is personal in such a way that it makes sense to a mass audience. Through the process of making the book I had to interrogate my own story to ensure that I was doing just that; to examine the narrative and understand what other information was needed to make it understandable and relevant. As a result, for instance, I compiled a whole bunch of statistics which demonstrated how “average” Basildon is and how representative of England. We worked on infographics to ensure that this information could be easily accessed by an audience. And, in doing so, this information helped ensure the narrative had journalistic integrity and fully explored the subject and was true to what I was trying to represent and what I had always thought to be true.

Olivier Laurent: In light of Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, does your book take on a new resonance?

CJ Clarke: Brexit, of course, gives the work an added urgency. The book documents the roots of Brexit Britain, a community that represents all of those areas in England which voted to leave. In this sense, it seeks to explain a community that rejected a common European identity in favor of a specifically English one.

Such communities have been ignored and belittled for too long. In the early 1990s the media coined the term Basildon Man to express the way in which the town was representative of England; but such nomenclature belittles the subject, it is a way of objectifying the working classes and delegitimizing their opinions.

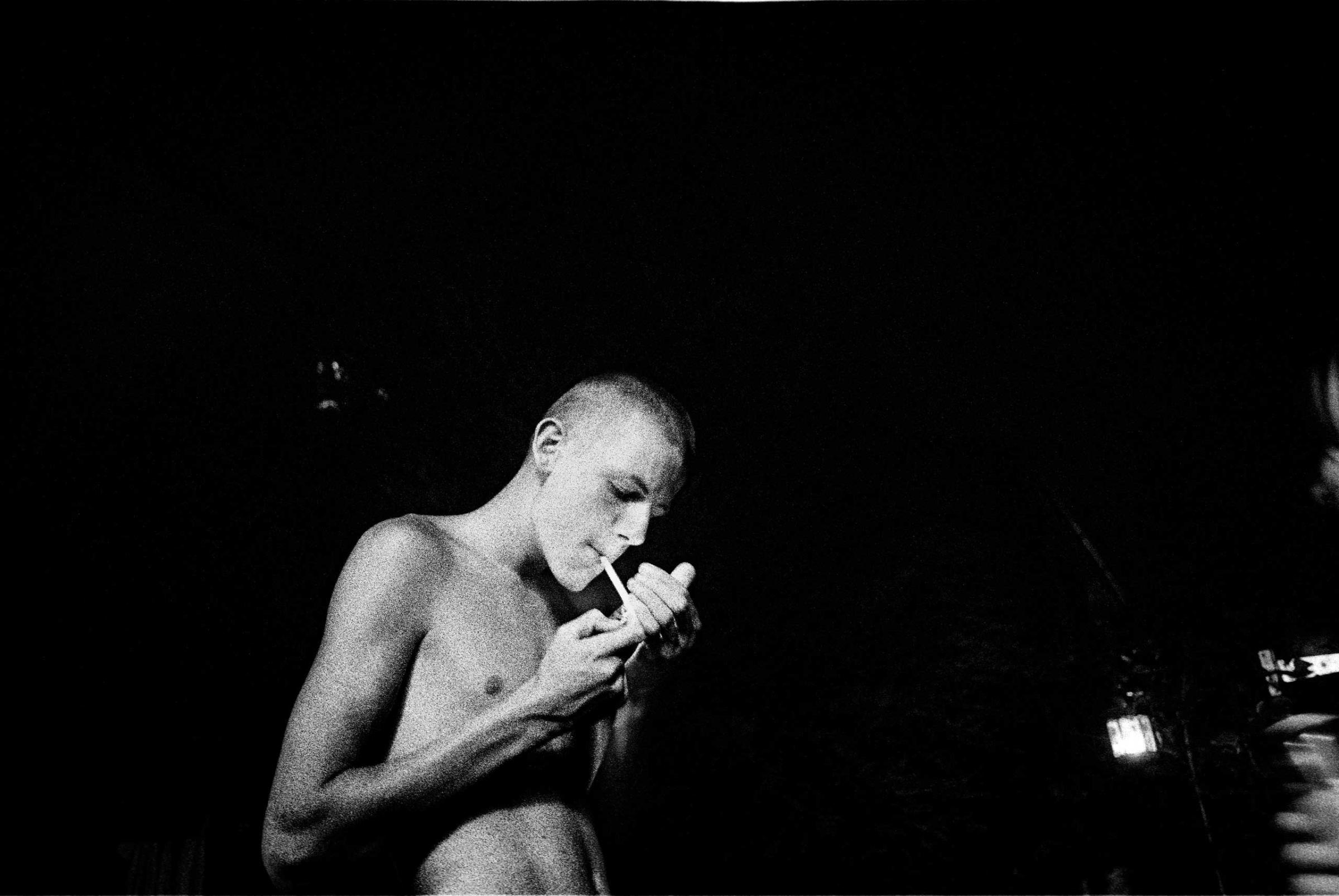

Magic Party Place was a reaction against such objectification. In 2005, I was new and fresh into photography and I kept seeing stories on the working class which either dealt in stereotype or in “extremes”: the working class are only relevant and interesting if they are drug addicts or criminals. This didn’t reflect the reality for a majority of those people who would label themselves as working class and it certainly didn’t reflect my reality coming from and growing up in such a community. The disconnect between the establishment – the elite, the political classes and the people they supposedly represent has always be clearly visible to me. This inability to connect, exists within Labour and Conservative. It is a chasm that is only growing wider and in Brexit, the disconnect has found its ultimate expression.

CJ Clarke is a documentary photographer and filmmaker based in India. Magic Party Place is published by Kehrer Verlag and available now.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com