Very rarely does footage released by Chinese authorities qualify as good cinema, and the video released on Tuesday of Hong Kong bookseller Lam Wing-kee in Chinese detention apparently enjoying his time in a prison cell is not an exception to this rule. It is bad because its star is unconvincing: we see the 61-year-old prisoner slurping noodles, reading books, and woodenly confessing to his crimes.

“Because I have breached China’s legal provisions, I am very remorseful,” he says to an off-camera interlocutor. “I hope the Chinese government will be lenient to me after this incident.”

Lam is not a very good actor, though there’s no reason he should be. He is one of five affiliates of a Hong Kong publishing house who disappeared late last year and resurfaced in the custody of mainland Chinese police. Four of his colleagues are believed to still be in China, with one, publisher Gui Minhai, still in detention, but Lam is out on bail, home in Hong Kong, where he has spoken openly about his harrowing eight-month incarceration — a story that is more credible than the one spun by his jailers.

Lam and the other four were arrested for their work at Mighty Current Media, printing and selling lurid books that speculated gleefully about the political antics and bedroom lives of Beijing’s political elite. Their clientele largely comprised tourists who came to Hong Kong from the mainland, eager to get their hands on the sort of unpatriotic pulp that is outlawed at home.

Mighty Current and its flagship bookstore set up shop in Hong Kong because Hong Kong is the only place in China where speech and press are nominally free. In the 20th century, as communist China cemented its status as the world’s least tolerant superpower, British colonial rule fashioned Hong Kong as a lively metropolis where democratic freedoms (if not democracy itself) flourished. When the British lease on the tiny territory expired in 1997, they relinquished it to China under a constitutional dynamic known as “one country, two systems,” designed to shield Hong Kong’s freewheeling political spirit from Beijing’s authoritarian impulse by giving the former a “high degree of autonomy.” Today, state censors in the mainland block access to Facebook, seeing it as a tool of political mobility; in Hong Kong, citizens log on to troll the page of Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, the territory’s top political leader widely vilified here as Beijing’s compliant puppet. (Leung is an avid gardener; he once posted a black-and-white picture of a tulip that has received more than 5,000 “Angry” reactions to date.)

Thus it is easy to envision the shock that rippled through Hong Kong’s collective psyche when people here learned that five of their own had been arrested for mere political impishness — and arrested not by their own police but by authorities in China who have no jurisdiction in the enclave. Lam and two colleagues were arrested while traveling in China. Gui was abducted from his holiday apartment in Thailand. But it was the snatching of the fifth associate, British citizen Paul Lee, also known as Lee Bo, by mainland agents from the streets of Hong Kong that has traumatized Hong Kong the most. All of a sudden, the Kowloon Hills that have always acted as a psychological if not physical barrier between Hong Kong and its seething hinterland seemed all too pathetically breached. For the first time in living memory, the kinds of Hongkongers who would attract Beijing’s unfavorable notice — the writers, and activists and outspoken academics — began to feel unsafe.

“I don’t think the Chinese government realizes how seriously this incident is affecting the fate of people in Hong Kong,” says Jonathan Man, a prominent human-rights lawyer who helped represent Edward Snowden during the whistle-blower’s stint as a refugee here. “It will make people afraid to express themselves, and that’s the worst thing.”

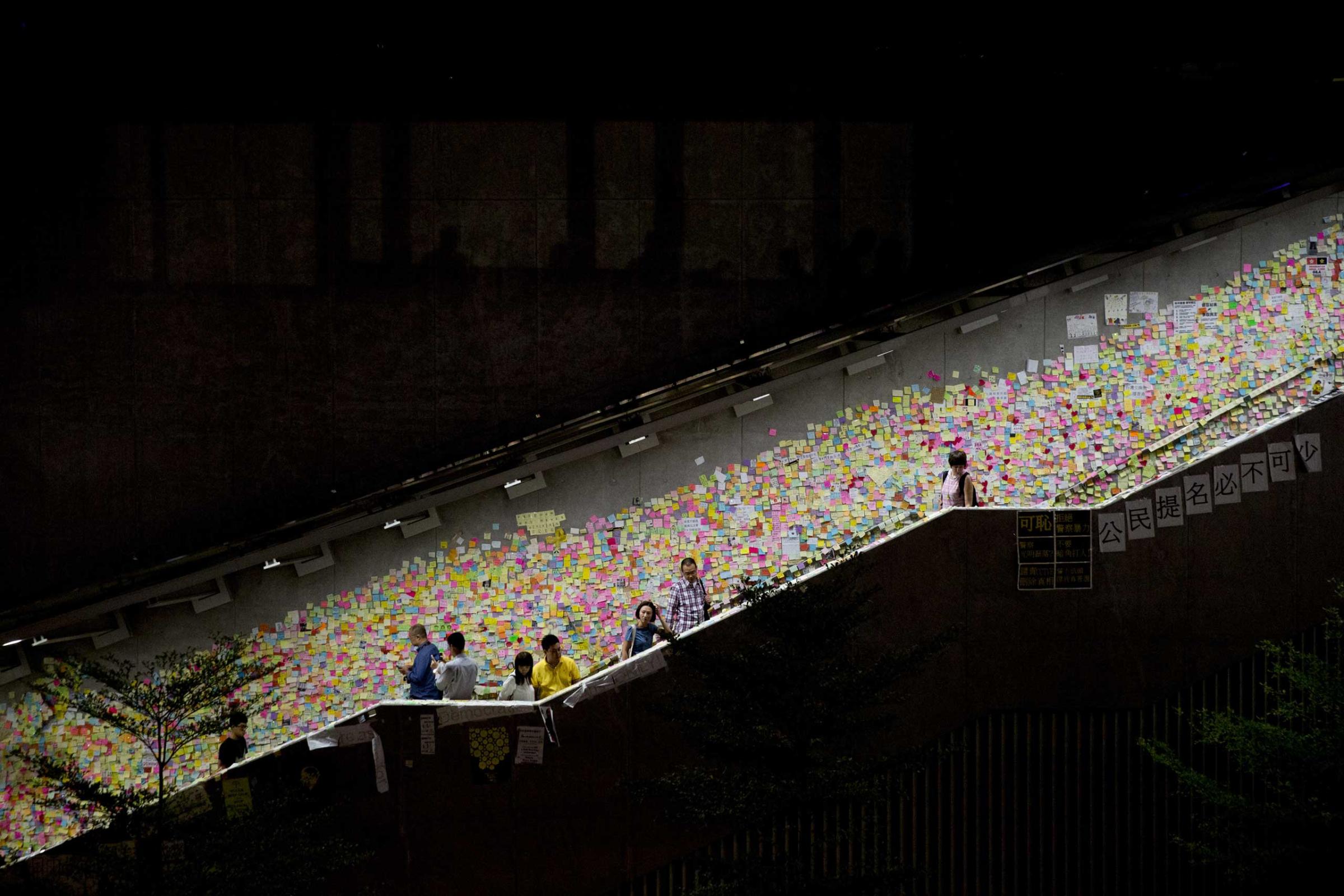

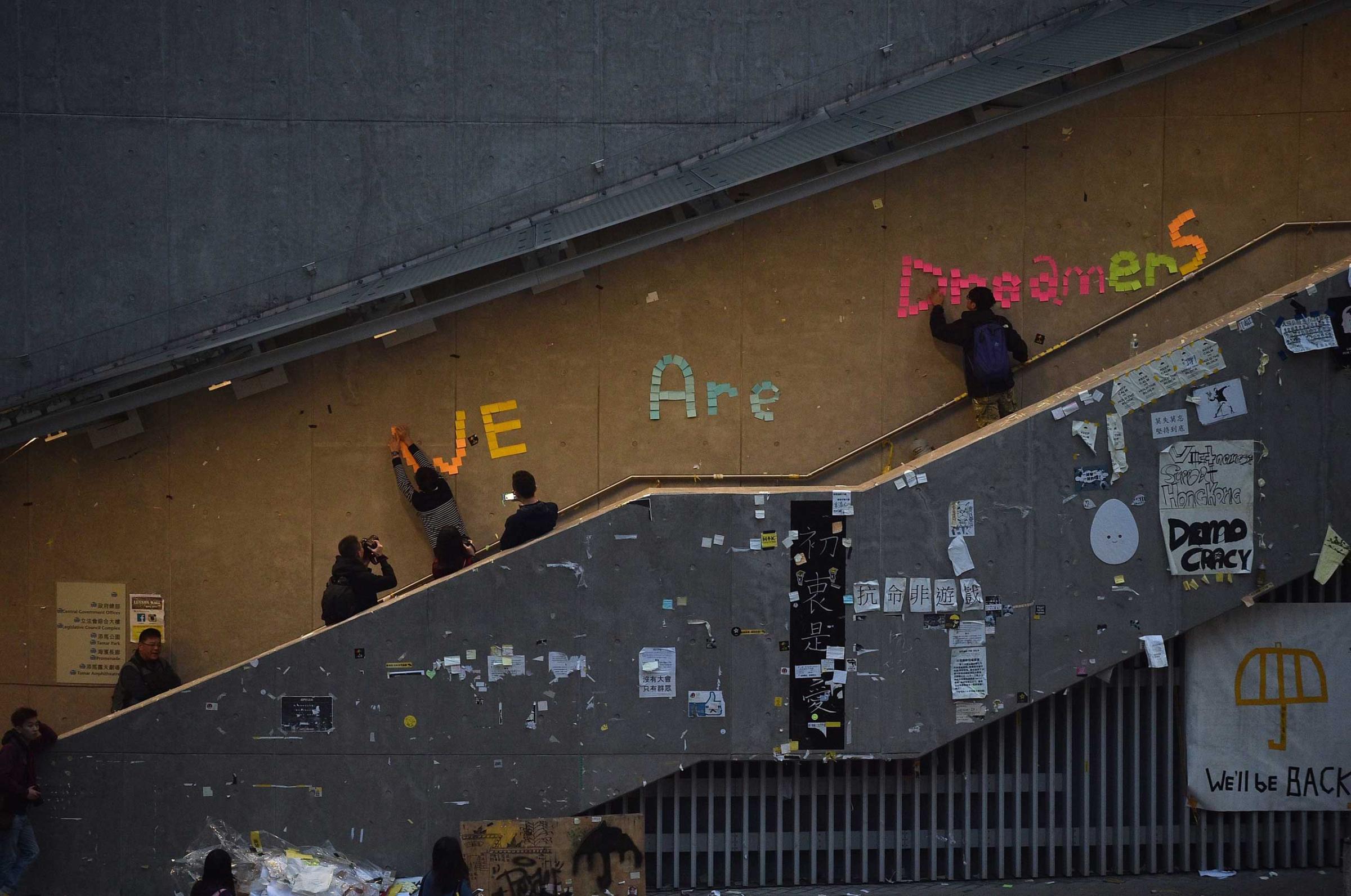

The case of Lam and his colleagues marks the most flagrant violation of the territory’s autonomy to date, and suggests to some that its precious freedoms are easily subdued in the face of Beijing’s caprice. In hindsight, it makes the then unprecedented tremors of the Umbrella Revolution — the audacious pro-democracy protests that brought Hong Kong to a standstill for three months in late 2014 — seem like a teatime squabble at the territory’s iconic Peninsula hotel.

“There has been no single incident that has so expressly invalidated ‘one country, two systems,'” says Man. “Hong Kong people used to know they could enjoy these books, but now, something that’s legal in Hong Kong but illegal in China means you can be subject to Chinese law. That’s what scares people the most.”

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

Last month, these fears were once again illuminated when Lam suddenly returned to Hong Kong, putatively out on bail. Several of his detained colleagues had been paraded on Chinese state television to “confess” to their crimes earlier this year, but Lam came home and held a defiant, dramatic press conference. For nearly an hour and a half, he described his detention to a rapt audience of reporters and television cameras. The flashbulbs erupting in his face emphasized his fatigue.

By his account: after being apprehended and blindfolded while crossing the border into China, he spent eight months in detention (five in solitary confinement), subject to constant surveillance and regular interrogation, unable to solicit legal help. He was forced to sign a statement admitting his guilt and pressured to cough up a list of his clients — mainlanders whose possession of a Mighty Current tome would be illegal. He said his jailers denied him basic items like toothbrushes out of fear that he would use them to kill himself.

He has since emerged as a grim sort of celebrity. July 1 is the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty, but Hongkongers mark the day by celebrating what makes the territory eminently un-Chinese — their right to march through town, from the old green expanse of Victoria Park to the ultramodern waterfront government complex nearly 2 miles away, and air their political grievances. Lam was slated to lead the march this year, but hours before it began, he dropped out, citing “serious” threats to his safety. On Wednesday, local media reported that police had offered him protection after he reported being tailed six times since his return to Hong Kong. “I am half-dead,” he told the newspaper Ming Pao.

Earlier this week, police in the mainland city of Ningbo, where he was detained, demanded that he return to their custody or face the undisclosed consequences of violating the terms of his bail. Lam has made it clear that he has no plans to return to mainland China of his own volition. The Hong Kong government’s secretary for security Lai Tung-kwok has also said that Hong Kong will not surrender Lam to China without an extradition agreement. This leaves two options. Beijing, as the sovereign power, simply brushes the demand for an extradition agreement aside and demands that the Hong Kong government facilitates Lam’s transfer across the border — or mainland authorities retrieve him themselves in the same extrajudicial manner in which they abducted Lam’s colleague Lee. Either would mean the end of Hong Kong’s autonomy.

“It must be acknowledged that this case is truly unique: a Hong Kong citizen detained in mainland China for political crimes based on mainland law,” says William Nee, who researches China at Amnesty International’s East Asia office in Hong Kong. “If the mainland side were to put pressure on Hong Kong to return him, it could set a dangerous precedent.”

Hong Kong’s government has engaged Beijing in dialogue on the issue, albeit reluctantly, and in terms that some have scorned as noncommittal. On Tuesday, a delegation of Hong Kong officials traveled to the Chinese capital to talk with leaders merely about the “notification mechanism” by which Chinese authorities inform Hong Kong that Hongkongers have been detained on the mainland.

“I think that from what we’ve seen from the Hong Kong government, they’re trying to say that the system is still there, and it’s impossible to have Chinese law enforced in Hong Kong,” Man says. The extent to which China cares is unclear. The release of the video montage of Lam’s imprisonment and confession was a strident move, but an “absolutely bizarre” one, Nee says. “It adds fuel to the public-relations disaster of their own making. The booksellers case has been handled in a way that is terribly damaging to China’s image.”

The world is now watching Hong Kong. The day after Lam’s homecoming press conference, both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal put him on the front pages of their U.S. editions. In an email to TIME on Wednesday, Darragh Paradiso, a public-affairs officer at the U.S. consulate general in Hong Kong, said that the U.S. was “troubled by Hong Kong bookseller Lam Wing-kee’s account of his time in solitary confinement in mainland China” — a sentiment echoed by a number of world leaders and a coalition of prominent U.S. lawmakers chaired by Senator Marco Rubio.

Some experts are optimistic that the poor optics that would result from Beijing’s unwarranted crackdown on a sophisticated metropolis — Hong Kong is frequently likened to an Asian New York City — will deter mainland authorities from coming after Lam. “Otherwise, the Chinese government would not give a damn,” Man says.

As for the bookseller at the center of the crisis, “I used to enjoy freedom from fear in Hong Kong,” Lam told Ming Pao. “But now it’s lost.”

This story has been updated to include a statement from Hong Kong government’s secretary for security, Lai Tung-kwok, who said that Hong Kong will not surrender Lam to China without an extradition agreement.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com