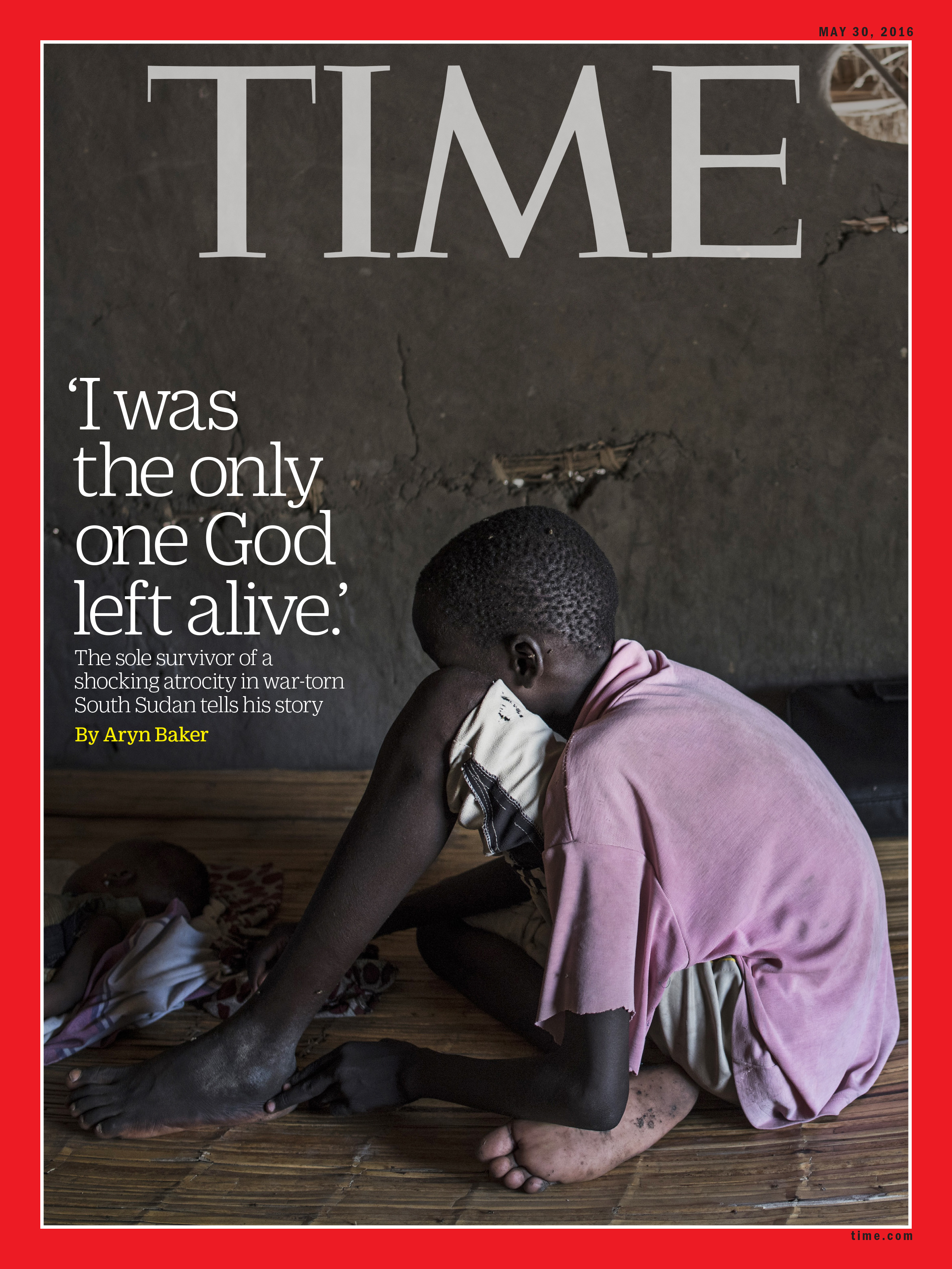

The 13-year-old boy lives as a refugee in his own country, crammed into a listing tent cobbled together out of plastic sheeting and timber scraps with his mother and multiple siblings. Sweltering in summer and swampy when it rains, their temporary home is no different than those of the thousands of other South Sudanese families huddling together for protection under the auspices of the United Nations. Most of the camp’s residents have no homes to return to, their villages, crops and herds of cattle destroyed in the brutal civil war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced millions since it started in December 2013, and continues to kill nearly a year after opposing sides signed a peace treaty in August.

The boy and his family still have a home back in Thonyor, in the north of the country. Hunger or mortar fire or rampaging soldiers didn’t force them out. They fled because the boy’s life was in danger. The boy, who isn’t being named in order to protect his identity, is the sole survivor of an October massacre in which government soldiers locked 53 men into a metal shipping container and left them to die. As such, he is a key witness to a likely war crime that, should it ever go to trial, could result in government forces being prosecuted for committing crimes against humanity. But the only thing keeping him safe from reprisal is the anonymity of a camp for the displaced—and even that is beginning to fray.

Read More: The Boy Who Lived

Ever since the Nuremberg trials after the end of World War II, the international community has agreed that war crimes should be punished so that they won’t be repeated. But there is a gaping hole in prosecution when it comes to protecting the witnesses of those war crimes. The boy, still traumatized by his experience in the shipping container, is just one example of how the inability to protect witnesses is subverting the quest for justice. “Overlooking witnesses’ need for protection undermines the whole process of trying crimes against humanity,” says Lucy Richardson, a former diplomat from New Zealand who just completed her PhD in international law at Geneva’s Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, with a focus on witness protection. “If people are not able to come forward and speak, how do you have a trial? And without trials, how can you have accountability? Without a way to secure witnesses, the whole idea just falls apart.”

I met and interviewed the boy near his home in March, but TIME did not publish the story until May, once the boy and his immediate family had been moved to a United Nations camp for the internally displaced where he would have some degree of protection from the risk of reprisal by government officials who could be implicated by his testimony. But the conditions are abysmal. The United Nations humanitarian mission in South Sudan, underfunded and overstretched like it is nearly everywhere else in the world, treats the boy and his family like every other displaced person in the camp. That means he often goes hungry, he gets no specialized trauma counselling (according to a new report by Amnesty International, there are only two practicing psychiatrists in the entire country) and his security cannot be guaranteed—he receives the same level of protection as anyone else in the camp. As a minor, the boy falls under the protection of Unicef, the United Nations emergency fund for children, but the group too is overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of children in desperate need of help. “UNICEF and partners continue to monitor the situation and stand ready to support the family, should the security situation change—while noting that witness protection is primarily the responsibility of the local Government,” says the organization’s New York-based spokesperson, Marixie Mercado, via email.

Read More: New Report Says Shipping Containers Are Being Used As Deadly Prisons in South Sudan

In a country of 11.3 million, where hometown and clan name are enough to identify a person, neighbors in the camp who know about the October incident have already figured out who he is. “They say, ‘you are the one who survived.’ But he is a small boy, so he doesn’t know to lie,” says John Kong, a South Sudanese social worker who helped the family relocate. “The people who did that crime, they know very well that they did something bad. They know they will be taken to justice, and they know what [the boy] saw. But for [his] family, they don’t know how to protect him. They just want to go home.”

In countries like the U.S., witnesses to crimes where intimidation—or worse—is a threat are often put into sophisticated protection programs before the trial. They are relocated to a different city or state, given new identities and offered robust security. But when it comes to war crimes, the issue is far more complicated. The International Criminal Court in The Hague, which focuses on war crimes and crimes against humanity, does not have a security force of its own, nor does it have a territory where it can relocate vulnerable witnesses. Instead, international law says that nations are responsible for keeping their own witnesses safe. But what happens when witnesses have evidence against the state itself?

“Because of the way international law works, when the state is the violator you have a problem,” says Ioana Cismas, a former consultant to the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Promotion of Truth, Justice, Reparation and Guarantees of Non-Recurrence. “Witness protection in international criminal justice is one of those key areas that deserves attention and doesn’t receive it.”

Read More: Eyewitness to Hope and Hell in South Sudan

In theory, witnesses could be relocated to other countries, but the ICC cannot force member nations to accept and support them, and few are willing to take on the responsibility. When they do, it’s on a case-by-case basis. That failure of international law came to light most recently in April, when the ICC case against Kenya’s vice-president William Ruto, who was charged with crimes against humanity in relation to post-election violence in 2007-2008 that saw an estimated 1,113 Kenyans killed, was dismissed on a lack of evidence. Key witnesses disappeared, were unwilling to testify or were killed under mysterious circumstances. Many observers attribute this week’s apparent extra-judicial killing of a prominent human rights lawyer named Willie Kimani, his client and a driver to a sense of impunity fostered by the failed ICC case. (Kimani was representing a motorcycle taxi driver who had been shot and injured by the police in April, and who faced a campaign of harassment and abuse when he complained to the authorities.)

In South Sudan, where a fragile peace is on the brink of collapse, truth, justice and reconciliation are vital components for continued stability. The shipping container incident is but one atrocity in a war defined by massacres, savage murders, rapes, and even forced cannibalism. If a 13-year-old witness in an UN-guarded camp is at risk, there is little hope that others will come forward in the war-crime cases that are necessary for the country’s continued healing. “Those testimonies are vital for securing a prosecution, but there is no system in place to protect them,” says Amnesty International’s South Sudan researcher, Elizabeth Deng.

South Sudan, like the United States, is not a signatory to the ICC. But the internationally backed peace agreement signed in August calls for a special tribunal to try war crimes committed during the two and a half-year long civil war between forces aligned with President Salva Kiir and those loyal to his former Vice President and rebel leader Riek Machar. The two formed a unity government in April, but have made no steps to establish the court. On June 7, President Kiir called for the tribunal element of the agreement to be scrapped in a New York Times Op-Ed, saying that it would perpetuate conflict. Vice President Machar was listed as a co-author, but he later denied that he contributed to the Op-Ed.

Either way, a failure to establish a tribunal leaves people like the boy and other witnesses to the country’s multiple atrocities in limbo, haunted by what they have seen, and, until justice is served, still vulnerable to attack or intimidation from their former captors and torturers. The boy misses his friends and his life back home; his mother misses the rest of her family. “They keep asking how much longer they will have to stay,” says Kong, who visits often.

He doesn’t know what to tell them. Fighting has flared anew in South Sudan, raising fears of a return to outright war, and with it, continued crimes. That is why protecting witnesses like the boy is so vital, says Hannah Stoddart, the Director of Advocacy and Communications for the London-based children’s NGO War Child. “If we want to prevent these kinds of conflicts in the future, we need to be able to show state and non-state actors that these atrocities will not be tolerated. The last thing you want is for child witnesses to feel intimidated against testifying, or being prevented from testifying, because they don’t have the support and protection they need.” But so far, no one is willing to offer it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com