Istanbul’s main airport was operating again on Thursday morning, less than two days after the devastating gun and suicide bomb attack here that killed at least 44 people. At the international arrival hall, workers replaced shattered panes of glass and affixed new tiles to the ceiling. Luggage in tow, travelers emerged from the baggage claim arriving from cities like Geneva, Mombasa and Riyadh, part of stream of travelers into and out of Ataturk airport, the third-busiest in Europe. At the near the taxi stand outside, black-clad police stood guard, guns at the ready.

The message was unmistakable: The machinery of trade and tourism in Turkey was still running, despite a recent wave of armed attacks that increasingly target ordinary civilians and foreign visitors. The attacks have devastated tourism, but the fact that the airport was open for business was a sign that the system has already adapted to a new normal of almost routine violence.

Read More: Turkey Has Become the New Front of ISIS’s War on the World

“We hope it will be over as soon as possible, but I think they’re not going to come to Turkey because of the attacks,” says Ahmet Sakar, 23, a clerk at a tourist agency booth in the arrival hall at Ataturk. “We’re waiting.”

In fact the airport reopened almost immediately following the attack on Tuesday night, with some flights continuing to land in spite of the chaos at the terminals. By contrast, it took twelve days for flights to fully resume at the main airport in Brussels following the March 22 attack there, which was claimed by ISIS militants. (Though ISIS hasn’t claimed the attack in Istanbul, Turkish and U.S. officials strongly suspect the terror group carried out the suicide bombings.)

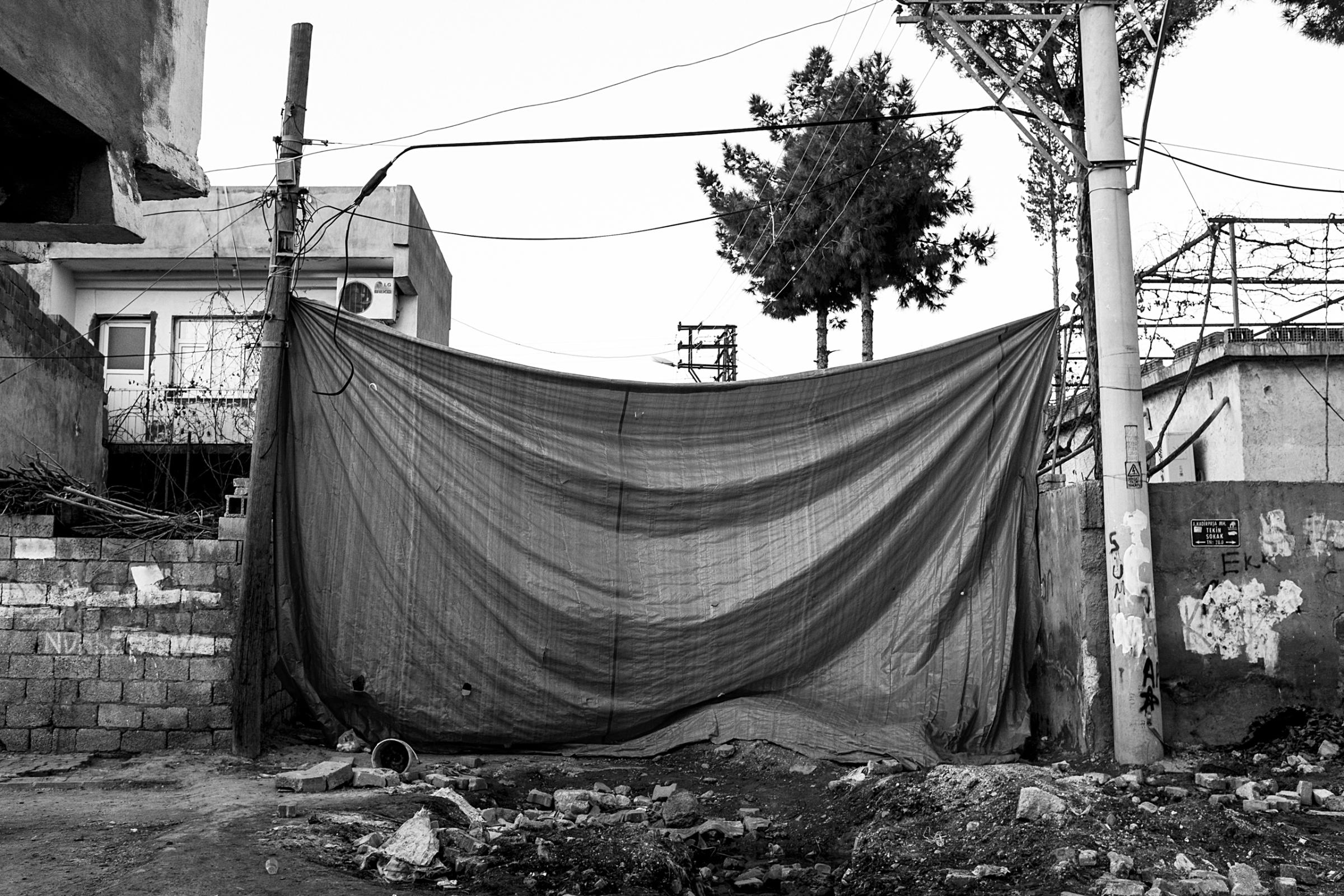

Photographing Turkey’s Hidden War

But any attempt to project an air of normality at the airport stood juxtaposed with the still raw trauma of the attack, the deadliest ever on an airport. On Thursday afternoon, hundreds of airline employees, travelers and officials filled a section of the cavernous departure hall for a memorial service. The crowds ringed a table laid out with the portraits of 15 slain airport workers and officials. The rows of screens over the check-in counters displayed black ribbons in place of destinations. Taps played over a loudspeaker before an imam led the crowd in prayer. Uniformed airline workers wiped away tears as they followed along with the preacher’s voice cracking with emotion.

The suspected ISIS militants who stormed the terminal on Tuesday struck one of the jewels of Turkey’s modern economic renaissance. The airport is a crossroads for travelers from all over the planet, a major transit point between Europe and the Middle East, and a symbol of Istanbul’s ambitions of being a paramount world city. On Tuesday night it was the scene of carnage.

Read More: Caught In the Middle of a Civil War Between Turkey and Its Kurds

Turkey—once seen as a haven of stability—can no longer escape the crises in the wider Middle East. One key source of instability is the five-year-old war in neighboring Syria, in which more than 400,000 people have died, and where the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad continues to battle an armed political insurrection. The chaos has forced millions of Syrians to flee and provided a foothold for extremist groups such as ISIS, which has been blamed for at least five attacks inside Turkey in the last year.

Turkish authorities are also grappling with violent domestic unrest. Last year the state resumed a decades-old conflict with Kurdish separatists, displacing more than 350,000 people in Turkey’s heavily-Kurdish southeast. Kurdish militants have also claimed a separate series of attacks that have killed both security forces and civilians. On June 10, a militant splinter group called the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons, which has claimed some of the deadliest recent attacks in Turkey, issued a statement warning foreign tourists: “You are not our targets, but Turkey is no [longer] secure for you.” Turkey has suffered at least eight major attacks attributed to either ISIS or Turkish militants over the last year.

The killings have lacerated the tourist industry. In May 2016, tourist arrivals were down 35% compared to May 2015. Barring further terror attacks, Turkey will pull in tourism revenues of $18 to $20 billion, down from $18-$20 billion in a good year, according to analyst Wolfango Piccoli of the consulting firm Teneo Intelligence. Taking into account direct and indirect income, tourism accounts for as much as 12 percent (or $96 billion) of Turkey’s GDP.

Until recently, ISIS had mostly focused on attacking pro-Kurdish activists in Turkey and other opponents in an extension of its battlefield in Syria, where it is pitted against the Kurds. But over the past year it has begun targeting civilians in Turkey as well. The recent attacks include two bombings at iconic Istanbul tourist destinations, including one in the historic Sultanahmet neighborhood in January and another in the usually thriving shopping and leisure district on Istiklal street. “The risk of attacks remains substantial,” says Piccoli. “The question here is whether ISIS has shifted its strategy to continue to attack the tourism industry because it’s a soft underbelly, at the same time not paying much attention to whether the victims are Turks or foreigners.”

The decline in tourism has also coincided with a period of growing rancor in Turkey’s relations with other world powers. After the military shot down a Russian fighter jet along the Syrian border in November 2015, a diplomatic crisis erupted. Russian President Vladimir Putin imposed sanctions on Turkey—long a popular destination for Russian vacationers—hampering tourism and economic ties.

Read More: Deadly Bombings in Turkey More Evidence Terror Has Come Home

That rift closed on June 29 when Putin spoke with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, resolving the row between the two countries. Putin also reportedly agreed to lift restrictions on Russian tourism in Turkey. The diplomatic rapprochement was striking, but the two countries remain on opposite sides of the civil war in Syria, with Russia supporting the Assad regime and Turkey backing the rebels.

Erdogan’s government also restored ties with Israel on June 27, stabilizing relations with yet another estranged regional player. The agreement ended a crisis resulting from the Israeli military’s killing of nine activists on board a Turkish-backed aid flotilla attempting to break the blockade of the Gaza Strip in May 2010.

On an inter-state level, the recent attacks on civilians in Turkey could push the country toward closer coordination with other countries. That includes compelling the government to take a more active military role in the fight against ISIS—something Washington has long urged Erdogan to do. “From a Turkey perspective, there is a hope that this will be a further sign indicating there is a need for furthering cooperation,” says Piccoli. “The problem is that the Turks have always been difficult partners in this kind of cooperation. The way they do antiterrorism is a bit different from the way in which other countries might want to do it.”

At Ataturk airport on Thursday afternoon, tourism workers were pessimistic. “In my opinion, nobody will come, except terrorists,” said a 47-year-old clerk at one tour agency in the arrival hall, who spoke on condition that his name be withheld for fear of reprisal. He was back at work, having survived the attack on Tuesday night by fleeing down an escalator with a crowd of terrified travelers. “If they don’t find any solution in Syria, it will continue like this.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com