Correction appended, July 8, 2016

Each year, as the United States of America prepares to celebrate its Independence Day, the urge to reexamine American history is inevitable. After all, it’s hard to escape what happened on July 4, 1776, when you’re marking a holiday known as the Fourth of July.

But revisiting American history doesn’t have to mean sticking with those red-letter dates. Last year, at around this time, we asked 25 historians to nominate 25 moments that changed the nation, and the list they generated was eye-opening. (You can read the whole thing here.) Animated by the breadth and insight of that round-up, as well as the knowledge that it was only the tip of the iceberg, we’ve asked 25 new experts to chime in with their own nominations.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The only rules: the selections had to be “moments” (a broad social movement doesn’t count) and they had to have happened during the span of the 20th century, inspired by TIME founder Henry Luce having declared those years “the American century.” The results were, unsurprisingly, another fitting reminder of just how much can happen in 100 years—and of the way that a single day can change all that comes after. From laws that were passed with unintended consequences to scientific advancements that still affect our everyday lives to a celebrity debut that made a difference, each moment in its own way is an example of how history’s hinges work.

Reasons for nominations as told to Lily Rothman

The Mann Act Is Passed (June 25, 1910)

Nancy F. Cott

On June 25, 1910, the Mann Act, or White Slave Traffic Act, made it illegal to transport “in interstate or foreign commerce . . . any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” Years of public alarm over “the traffic in women” and “white slavery”—language based on public officials’ assumptions that women in sex work must have been tricked or coerced—had produced the new law, but it would have consequences that went far beyond its immediate intent. The language of “immoral purpose” in the law proved to be elastic. Prosecutions under that rubric multiplied, catching unmarried consensual couples in its snare; federal authorities used the Mann Act to target individuals wanted for other reasons. Even more important in the long run, the Act’s creative use of the federal government’s constitutionally-mandated control over interstate commerce inaugurated the huge expansion of federal powers over citizens’ daily lives that would take place in the 20th century.

Nancy F. Cott is Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History at Harvard University and president of the Organization of American Historians.

Read about Charlie Chaplin’s Mann Act trial, here in the TIME Vault

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act Is Passed (Dec. 17, 1914)

Scott C. Martin

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act — legislation that imposed a tax on anyone who imported, produced, sold or distributed opium or its derivatives — was ostensibly designed to require physicians, pharmacists and others who dealt in opiates to acquire a license at a nominal fee, and to keep detailed records of to whom they distributed the drugs. One clause of the act provided that a physician could prescribe opiates “in the course of his professional practice only.” Federal courts subsequently interpreted this to mean that doctors could prescribe opiates for pain, but not to maintain addicts so that they would not experience withdrawal symptoms. This judicial interpretation criminalized addiction and transformed the Harrison Act from tax to prohibitory legislation—and inaugurated a federal war on drugs that continues to the present day. The definition of drug abuse and addiction as legal offenses rather than medical conditions dates, in many ways, to the Harrison Act.

Scott C. Martin is a professor of history at Bowling Green State University and past president of the Alcohol and Drugs History Society.

Read about the Harrison Act and Prohibition, here in the TIME Vault

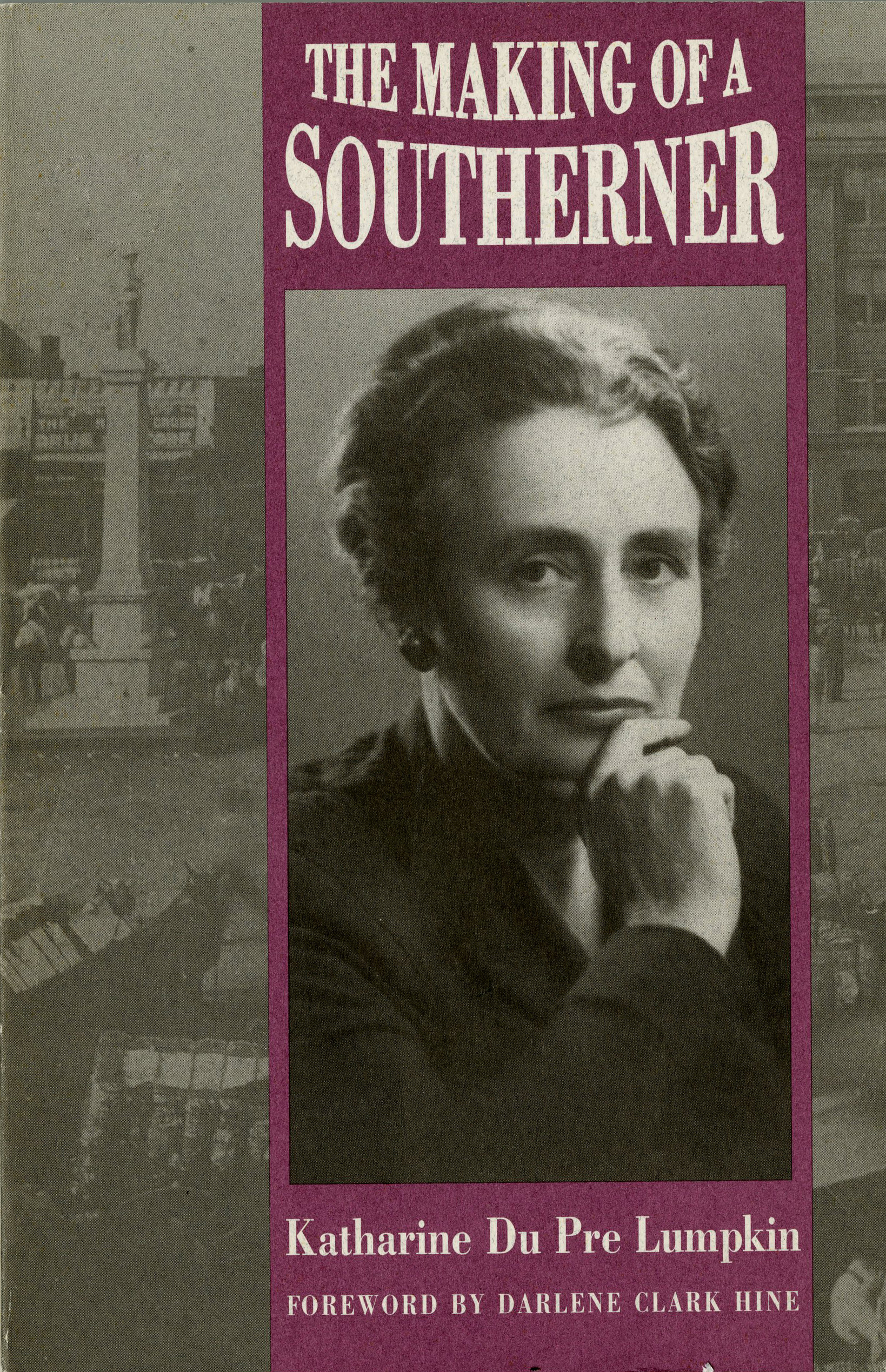

Katharine Du Pre Lumpkin Uses the Word “Miss” (Late 1915, Date Unknown)

Ed Linenthal

Historical change often comes not only in “big” events, but also in the struggles of people to enter a new world of meaning. Katharine Du Pre Lumpkin describes one such shift in her 1946 autobiography The Making of a Southerner. Lumpkin—who grew up in a “Lost Cause” family in Georgia, adhering to rigid racial classifications and a strong nostalgia for the old South—tells of a 1915 incident at her college when an African-American woman, a YWCA staff member, was going to address a leadership conference. Lumpkin writes beautifully of her struggle to address the woman as “Miss.” Just using that term of respect challenged an entire worldview of white supremacy. Lumpkin wasn’t the only one confronting the limitations of the world in which she grew up. Though movements are more than the results of any individual’s actions, it is with those actions that worlds begin to crumble and be remade. What could be more telling of the embryonic stages of change?

Ed Linenthal, professor of history at Indiana University, is editor of the Journal of American History.

Read more about the “lost cause” mythology, here in the TIME Vault

The Bedford Camp Experiment Begins (June 4, 1917)

Michelle Dunn

When the United States entered World War I and the nation’s men were sent overseas to Europe, the scarcity of farm labor became a pressing issue: with our farm laborers away, how would we feed our nation at home? Virginia Gildersleeve of Barnard College proposed a solution. On June 4, 1917 she helped open the Women’s Agricultural Camp in Bedford, N.Y., led by Delia West Marble and Dr. Ida Ogilvie. There young women were immersed and trained in the techniques of farming. That summer, they realized their grassroots program had nationwide potential. Within a 2-year period, over 20,000 “farmerettes” of the Women’s Land Army of America replaced male laborers in 42 states. Years before Rosie the Riveter, the image of the farmerette inspired women to challenge traditional gender roles and served as a big boost to the suffragist movement. In proving that a woman could do the same job a man could do, they raised an important question: why don’t women have the same rights too?

Michelle Dunn is a historical researcher for Drunk History on Comedy Central.

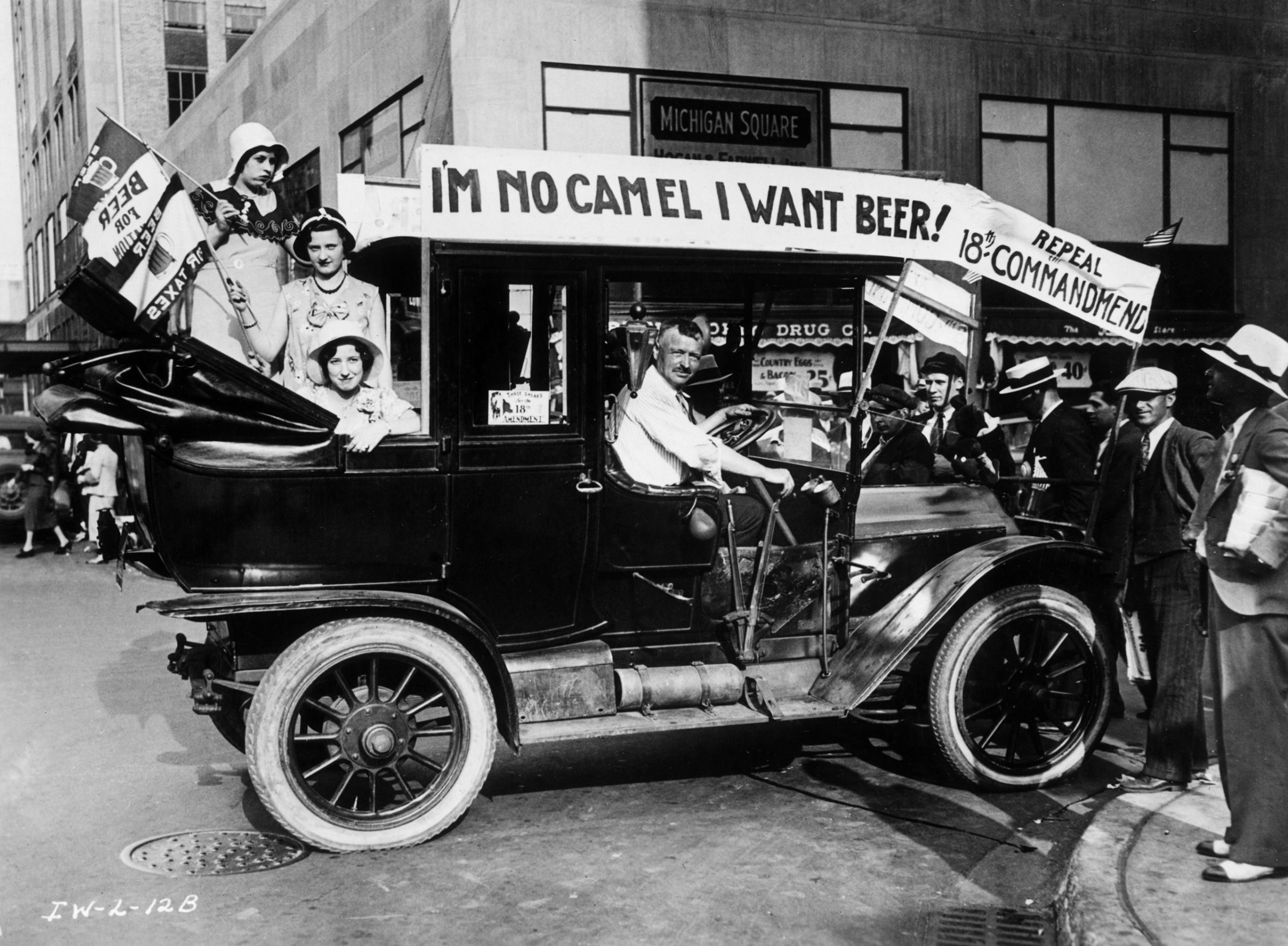

The Volstead Act Takes Effect (Jan. 17, 1920)

Kyle Volk

The 18th Amendment prohibited “intoxicating liquors” but left questions unanswered: namely, what did that mean? Many thought only hard spirits would be banned while beer and wine would remain legal. But the Volstead Act—the federal law that implemented Prohibition—strictly banned beverages containing more than 0.5% alcohol. The day it took effect, the U.S. officially went dry, and Americans quickly realized what Prohibition would really mean. With the nation’s fourth largest industry—the alcohol industry—outlawed, organized crime, bootlegging and speakeasies infamously filled the vacuum. But Prohibition wasn’t enforced equally everywhere: authorities and citizens’ groups, including the KKK, especially targeted immigrants and African-Americans. For these Americans and others, it was the first time they felt the power of the federal police state in their everyday lives. Backlash to the Volstead Act helped grow the Democratic coalition that elected President Franklin Roosevelt in 1932. His legalization of light beer and wine and the later passage of the 21st Amendment would end America’s “noble experiment” with Prohibition, but not before it transformed the nation.

Kyle Volk is a history professor at the University of Montana and winner of the 2015 Merle Curti Prize for the best book in American Intellectual History, for Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy.

Read more about the Volstead Act, here in the TIME Vault

The 19th Amendment Is Ratified (Aug. 18, 1920)

Mary Huffman

The ratification of the 19th Amendment did more than give women the right to vote. It was also a stepping-stone to many other areas of progress by women, from higher education and the professions to economic rights and even being able to serve on a jury. The ratification was the product of more than 70 years of fighting, going all the way back to women like Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton met in Seneca Falls, N.Y.

In my fifth-grade classroom, we study from Civil War Reconstruction to present times, and my students—particularly the girls—notice that we start with African-American men getting the right to vote, but not women. They get really upset by that, and I have to tell them that women were seen as inferior. When we got to the 19th Amendment this year, they cheered. It brought tears to my eyes. It’s an empowering moment, from back then all the way to 2016.

Mary Huffman, a fifth-grade teacher at Charles Pinckney Elementary in Mount Pleasant, S.C., was named 2015’s National History Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Read more about the 19th Amendment, here in the TIME Vault

Charles Lindbergh Reaches Paris (May 21, 1927)

Nathaniel Philbrick

Until Charles Lindbergh successfully completed his transatlantic flight in 1927, the United States had lagged far behind Europe when it came to aviation. It really wasn’t until the country woke up to learn that Lindbergh had flown across the Atlantic on his own that Americans began to realize, Wow, this is where our future lies. This was before highways were built throughout America, but after Lindbergh you began to see there could be a highway in the sky. Everybody was suddenly looking up. And at the time Lindbergh was a hero throughout the world, helping to resolve some of the post-war bad feelings between the U.S. and Europe, creating a global feeling of wonder. Somehow he had done something that no one else had been able to do before, and he had done it with such seemingly quiet modesty that it was absolutely galvanizing for the nation. He was TIME Magazine’s first Man of the year and his victory tour united the country. As far as people’s perceptions of what flight could do, he changed everything.

Nathaniel Philbrick is a winner of the National Book Award for nonfiction, the Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt Naval History Prize and the Albion-Monroe Award from the National Maritime Historical Society. His latest book is Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold and the Fate of the American Revolution.

See Charles Lindbergh as the first-ever TIME Person of the Year, here in the TIME Vault

The Census Uses ‘Mexican’ as a Race (April 1, 1930)

Pablo Mitchell

As far back as the 19th century, when what had been part of Mexico became part of the U.S., people of Mexican heritage had been considered “white” according to the U.S. government. That changed in 1930 when the U.S. census bureau decided to classify them—immigrants and their descendants alike—as racially “Mexican.” The decision came at a time of hardening racial divisions in the United States: the 1920s had seen the reemergence of the KKK; the institution of the one-drop rule for African-Americans; and immigration restrictions targeting Asians, Southern Europeans and Eastern Europeans. At the time, Mexicans were the bulk of agricultural workers in the Southwest, but after the Great Depression hit they were targeted for deportation—not just immigrants, but American citizens of Mexican heritage as well. Thanks largely to the work of civil-rights activists, the census designation was changed back in 1940, but not before the impact had been made. That short period solidified the identity of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans as non-white, a perception that persists to the present.

Pablo Mitchell is professor of history and associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Oberlin, and a winner of the Ray Allen Billington Prize from the Organization of American Historians. He is the author of several books, including the textbook History of Latinos: Exploring Diverse Roots.

Read more about Mexican immigration in the 1930s, here in the TIME Vault

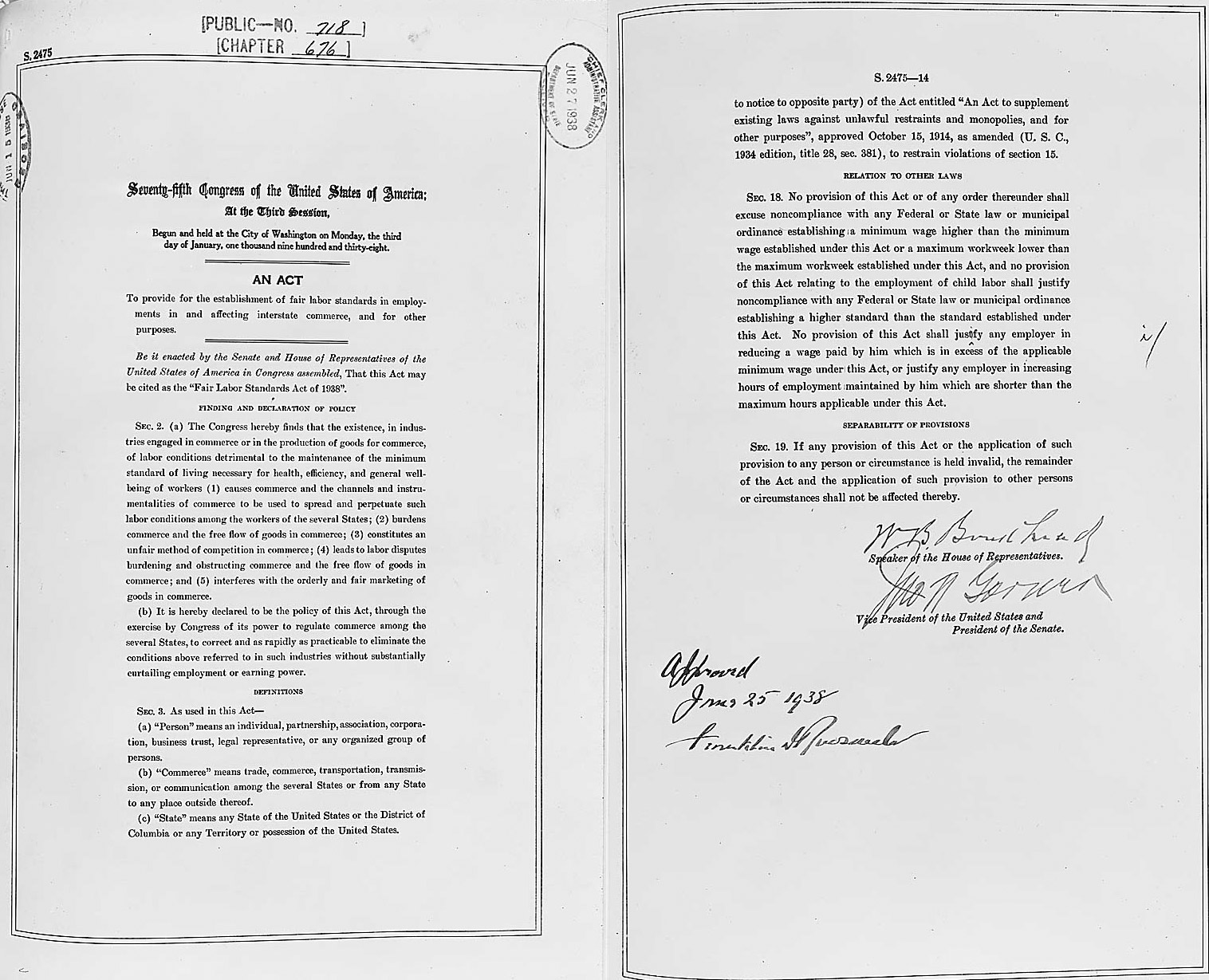

FDR Signs the Fair Labor Standards Act (June 25, 1938)

Nancy Woloch

Throughout the Great Depression, President Roosevelt’s mail filled with letters from workers saying that, if they had jobs at all, their wages were depressed and they lacked leverage to demand more pay or better conditions. That changed with the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The act established basic labor standards like the minimum wage, time-and-a-half overtime pay, and a ban on child labor. Passed by Congress after intense controversy, the law was a triumph for Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins and for the administration. It would not have been possible had the Supreme Court, which had long rejected New Deal labor laws as unconstitutional, not reversed course in 1937 and upheld a state minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish. The FLSA at first reached only a portion of employees, But it has shaped labor law ever since, and, as we have recently seen, the minimum wage and overtime pay remain vibrant issues.

Nancy Woloch’s latest book, A Class by Herself: Protective Laws for Women Workers, 1890s-1990s, was a winner of the Philip Taft Prize in Labor and Working-Class History and the William G. Bowen Award for the Outstanding Book on Labor and Public Policy.

Read more about the FLSA, here in the TIME Vault

Leroy Henry is Pardoned (June 17, 1944)

Mary Louise Roberts

Leroy Henry was an African-American soldier who was court-martialed and convicted for allegedly raping an English woman in Bath during the spring of 1944, when American troops occupied England awaiting the landings in France. Henry was sentenced to be hanged, but the English—who had not widely understood the extent of racism in the United States—were outraged. Their press reported on the case and it became a cause célèbre. And when Thurgood Marshall (pictured), then legal counsel for the NAACP, wrote a plea for pardon to Dwight Eisenhower, the General listened. The case brought international attention to the Jim Crow system of racial discrimination, but it was the pardon that showed that Eisenhower knew it: if the U.S. were going to fight against a racist Nazi regime, the country would have to do something about its own “peculiar problem,” as one British journalist put it. The Henry pardon represented a change in national consciousness, the moment when America realized that being a world leader would mean letting go of Jim Crow.

Mary Louise Roberts is professor of history at the University of Wisconsin Madison and a winner of the George Louis Beer prize from the American Historical Association for What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American G.I. in World War II France.

Read more about Leroy Henry’s case, here in the TIME Vault

Human Plutonium Experiments Begin (April 10, 1945)

Kate Brown

The world’s first micrograms of plutonium produced at the Manhattan Project secret site “W” in Richland, Wash., were sent to Los Alamos for tests of a new atom bomb, but that wasn’t their only destination. Plutonium also went to several hospitals within the Project. The first human plutonium injection occurred on April 10, 1945. The human subject called “Hp 12” was Ebb Cade, a 55-year-old African-American cement mixer who landed in the Manhattan Project Army Hospital in Oak Ridge, Tenn., after an automobile accident that left him with several broken bones. Researchers hoped to harvest bone samples, liver and other organs after the man died. Suspicious of his “treatment,” he ran away from the hospital, expiring eight years later of heart failure. But he was only the first of hundreds of thousands of people subjected to voluntary and involuntary medical radiation experiments in the four decades that followed. Cade’s injection marked the start of a troubling phase in American history, during which individual rights were sacrificed for the supposed good of a nuclear nation.

Kate Brown, a professor of history at University of Maryland Baltimore County, is the author of Plutopia, which won the 2015 John H. Dunning Prize from the American Historical Association, for the best book in American history in the last two years.

Read more about the Manhattan Project, here in the TIME Vault

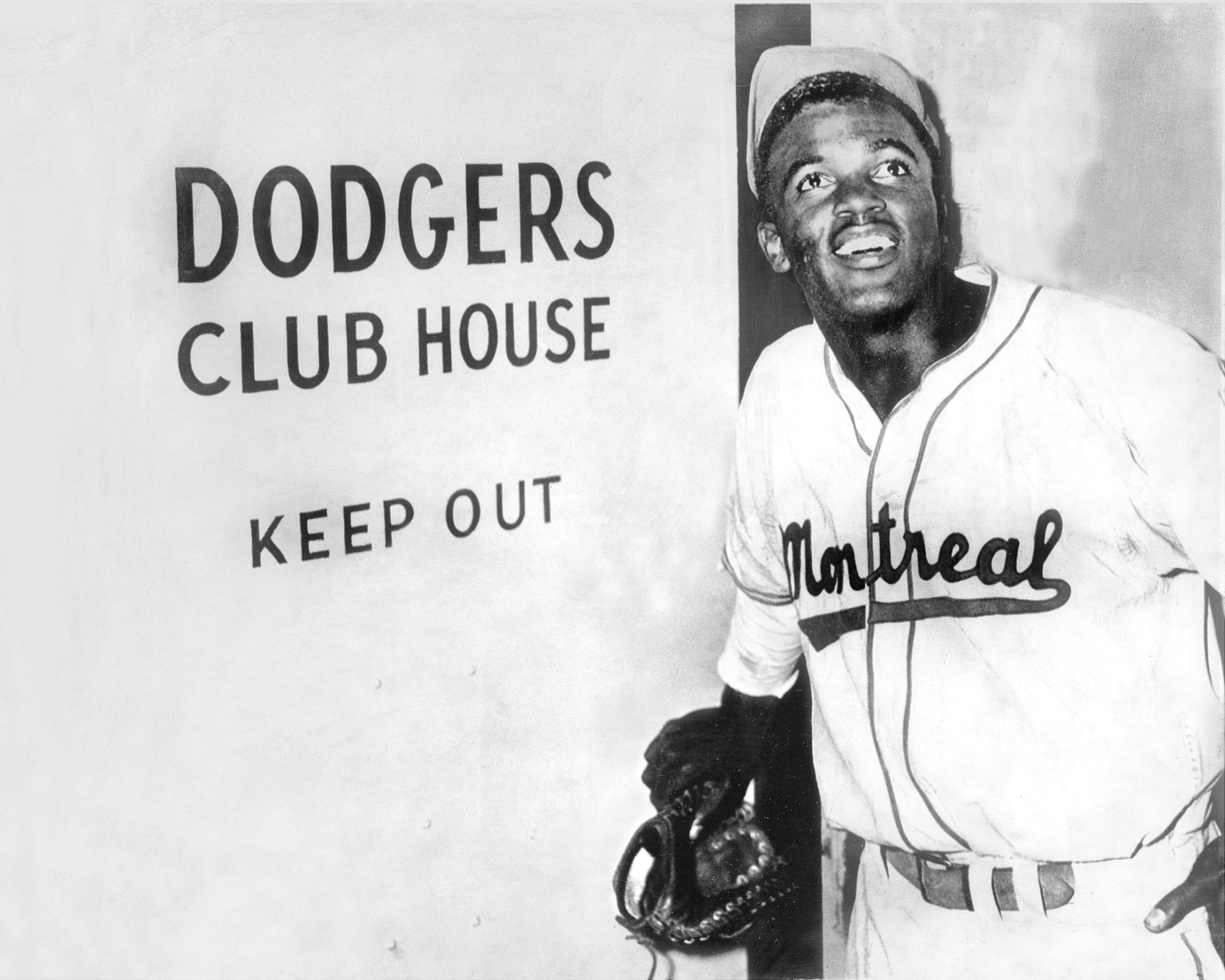

Jackie Robinson Plays His First Regular Season Game With the Brooklyn Dodgers (April 15, 1947)

James Grossman

When Jackie Robinson took the field as first baseman for Brooklyn, it was the first time in more than half a century that an African American participated in a major league baseball game. During the Jim Crow era the sport resembled the many other arenas of life in which African Americans built parallel institutions for themselves. But, despite the success of many Negro League teams, the color of Major League baseball remained white. The substantial role of African American soldiers in WWII, combined with increasing black populations in northern cities, created a fertile environment for change. Branch Rickey, president of the Dodgers, recognized the potential rewards that could be reaped from taking the substantial risks involved in signing black players. Jackie Robinson was prepared to take an even greater risk. His breaking the baseball color line was just one part of a larger process of eliminating the racial barriers that had been built since Emancipation to ensure the persistence of white supremacy in American institutional life. It took a dozen years before all major league teams had at least one black player.

James Grossman is executive director of the American Historical Association.

Read more about Jackie Robinson, here in the TIME Vault

Correction: A photo caption in the original version of this article misstated which team Jackie Robinson played for before the Dodgers. It was the Montreal Royals.

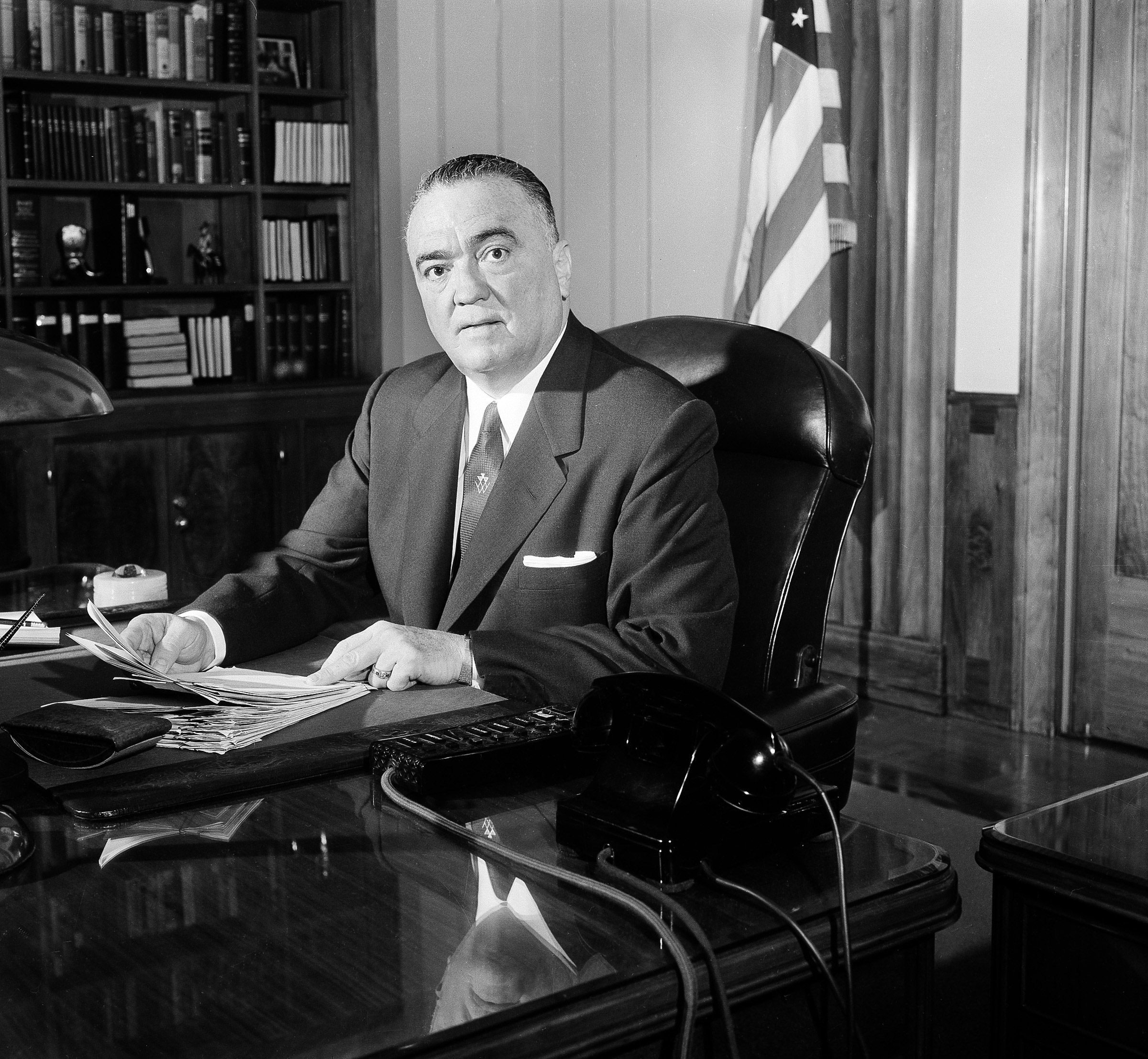

The FBI establishes COINTELPRO (August 1956)

Elizabeth Hinton

In 1956, the FBI established COINTELPRO—the Counterintelligence Program, a secret surveillance and disruption project—to monitor the activities of the Communist Party. But, in the immediate aftermath of riots in the summer of 1967, J. Edgar Hoover turned its attention toward groups like the Southern Christian Leadership conference, the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee and the Black Panther Party, which Hoover saw as the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States. His mission was to maintain social and political order, and the Black Panther Party was calling for a much different kind of order. COINTELPRO was not only responsible for some of the most devastating incidents of government oppression in the history of the United States, but it also severely compromised the potential transformative dimensions of many civil rights and black power groups. If COINTELPRO hadn’t meddled, raided many organizations and subjected leaders to exhaustive surveillance, who knows what the United States might look like today?

Elizabeth Hinton is assistant professor of history and of African and African American Studies at Harvard and author of the new book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America.

Read more about COINTELPRO, here in the TIME Vault

The Feminine Mystique Is Published (Feb. 19, 1963)

Juan Williams

The publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique signaled a cultural shift in American life, as Friedan argued that white, suburban women live with a “problem that has no name.” She identified the problem as women’s discontent with playing the happy housewife as they felt their intellectual, emotional and sexual lives go wasted. In the decades since, as American women have tried to correct that problem, we have seen the rise of women in the American workforce and educational system; an increased independence that has also affected family life, with more births to single women and more divorce; and a greater presence for women in politics, from the Supreme Court to the presidential race. This wave of change has also challenged gender norms around the world. This incredible shift is rooted in Friedan’s book, which spurred half of the American population to take a new look at what they wanted for themselves—and to begin a social revolution that continues.

Juan Williams, a political analyst for Fox News Channel, is the author of We the People: The Modern-Day Figures Who Have Reshaped and Affirmed the Founding Fathers’ Vision of America.

Read more about Betty Friedan, here in the TIME Vault

JFK Signs the Community Mental Health Centers Act (Oct. 31, 1963)

Anne E. Parsons

When President Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Centers Act, he signaled that the way America addressed mental health was changing. At the time, mental hospitals were the primary place for people to receive psychiatric treatment. About a half million people resided in such institutions in the United States. The Community Mental Health Centers Act allocated $150 million to create community centers to replace those large institutions. It represented a tidal shift in psychiatry towards community care. Over the next few decades, states closed mental hospitals across the country. Unfortunately, the vision of the bill never came to fruition. Services for people with serious psychiatric disorders became fragmented. Reformers had envisioned a robust mental health system in local communities, which was never fully funded. While the number of mental hospitals dropped dramatically between 1960 and 1990, states did not create enough social services to adequately care for people with psychiatric disorders, leading to homelessness and the rise of psychiatric services in prisons and jails.

Anne E. Parsons is assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and chair of the Committee on the Status of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Historians and Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

Read more about Kennedy’s work on behalf of mental health, here in the TIME Vault

New 1975 Auto Standards Are Announced (Jan. 30, 1971)

Andrew Lipman

As Americans took to the road during the postwar boom in car travel, the amount of tetraethyl lead in the nation’s air and soil rapidly increased. Things got so bad that when President Richard Nixon created the Environmental Protection Agency, one of the agency’s first official regulations decreed that American cars would have to run on unleaded fuel by 1975. Further regulations entirely phased out leaded gas over the next two decades. Many public health scholars believe heavy auto emissions in urban areas from the 1940s on factored in the crime spike of the 1960s, as the first generation exposed to dangerous levels of lead came of age. (Children exposed to lead are far more likely to suffer from poor impulse control, hyperactivity and brain damage.) And likewise the decline in environmental lead in the 1970s may have contributed to the drop in violent crime in the 1990s that continues to this day. While the link between tailpipes and murder rates is not a simple one, research strongly suggests that cities with cleaner air and playgrounds became safer cities.

Andrew Lipman is assistant professor of history at Barnard College, Columbia University. His first book, The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast, won the Bancroft Prize in American History.

Read more about the coming of unleaded gas, here in the TIME Vault

George Jackson Is Killed (Aug. 21, 1971)

Dan Berger

George Jackson went to prison as an 18-year-old and was killed at age 29 in an alleged escape attempt from San Quentin—and yet he was able to emerge as an author, activist and powerful analyst of what we now call mass incarceration. Writing when the prison system was a fraction of the size it is today, Jackson diagnosed the dangers of ubiquitous incarceration. His insights inspired many people. All the way across the country, prisoners in Attica held a one-day silent fast in response to his death. Three weeks later, a mundane fight erupted into the largest prison riot of the time period. The combination of Jackson’s death, the uprising at Attica and the killing of 39 people by N.Y. State Troopers retaking the prison all showed the problem of prisons. Citizens became more aware of the danger of punishment being so severe—even as politicians moved further in that direction.

Dan Berger is assistant professor of history at the University of Washington, Bothell, and winner of the 2015 James A. Rawley book prize for Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era.

Read more about George Jackson, here in the TIME Vault

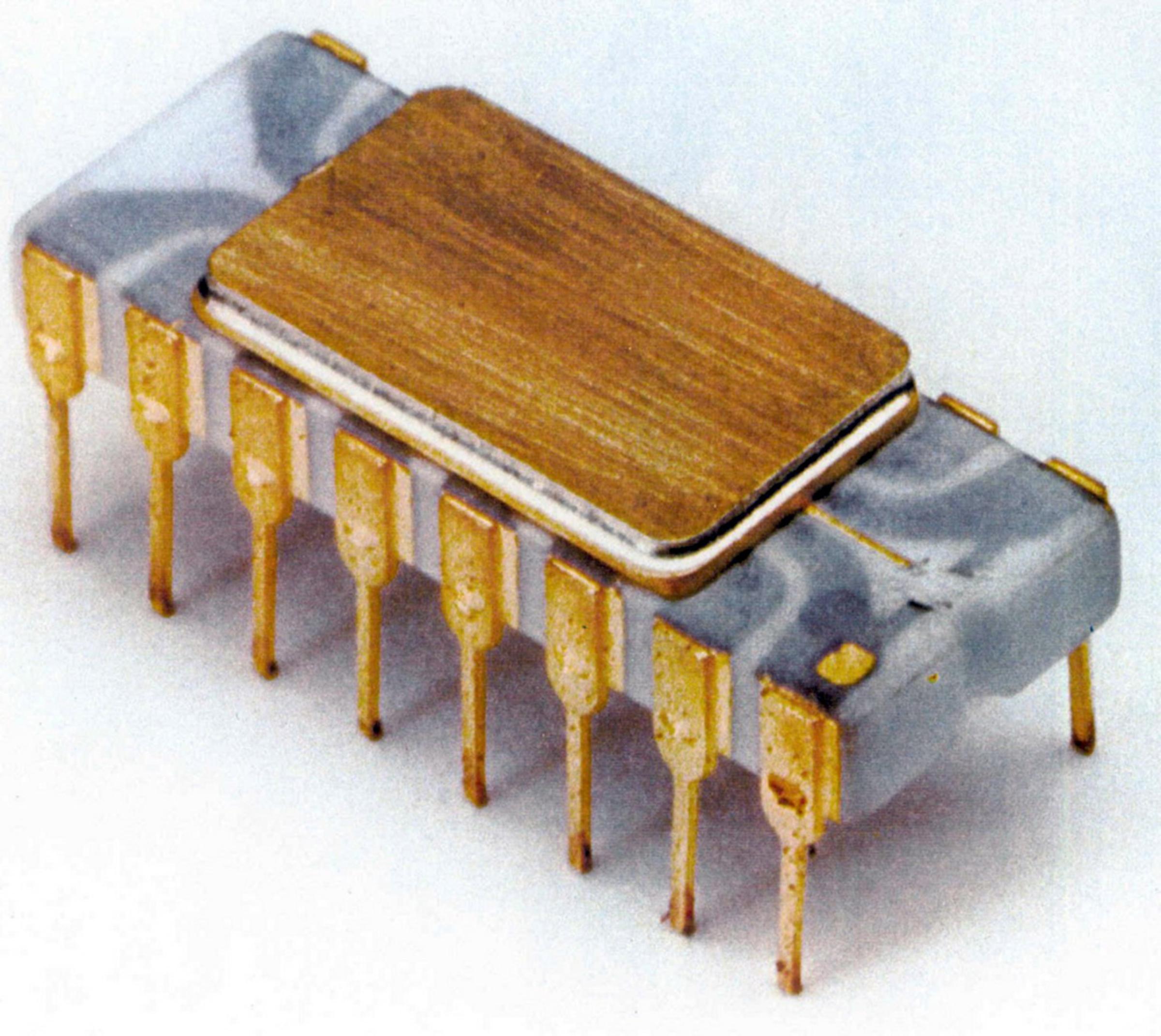

Intel Advertises Its New Microprocessor (Nov. 15, 1971)

Lynn Hunt

A microprocessor is a computer on a chip. The Intel 4004 measured 0.11 x .15 inch and by today’s standards was incredibly slow; it could process 60,000 instructions a second, versus the millions of instructions today’s chips can process. Intel had developed the 4004 for a Japanese manufacturer of calculators but came to see its wider applicability and bought the rights to market it. On Nov. 15, 1971, the company released an advertisement in a trade journal, “Announcing a new era of integrated electronics.” This very small object promoted many big changes. Constant advances in microprocessor capacities fueled the computing revolution. As a consequence, some experts consider it the most significant technological invention since the wheel. Mainframes became smaller and more powerful; personal computers brought word processing, email and video games to ordinary homes; and microprocessors enhanced everyday products from coffeemakers and cars to phones, watches and toys. Microprocessors power driverless cars and the wide range of assisting devices for the disabled that are continually improving.

Lynn Hunt is professor of history emerita at UCLA and the author of Writing History in the Global Era

Read more about the microprocessor, here in the TIME Vault

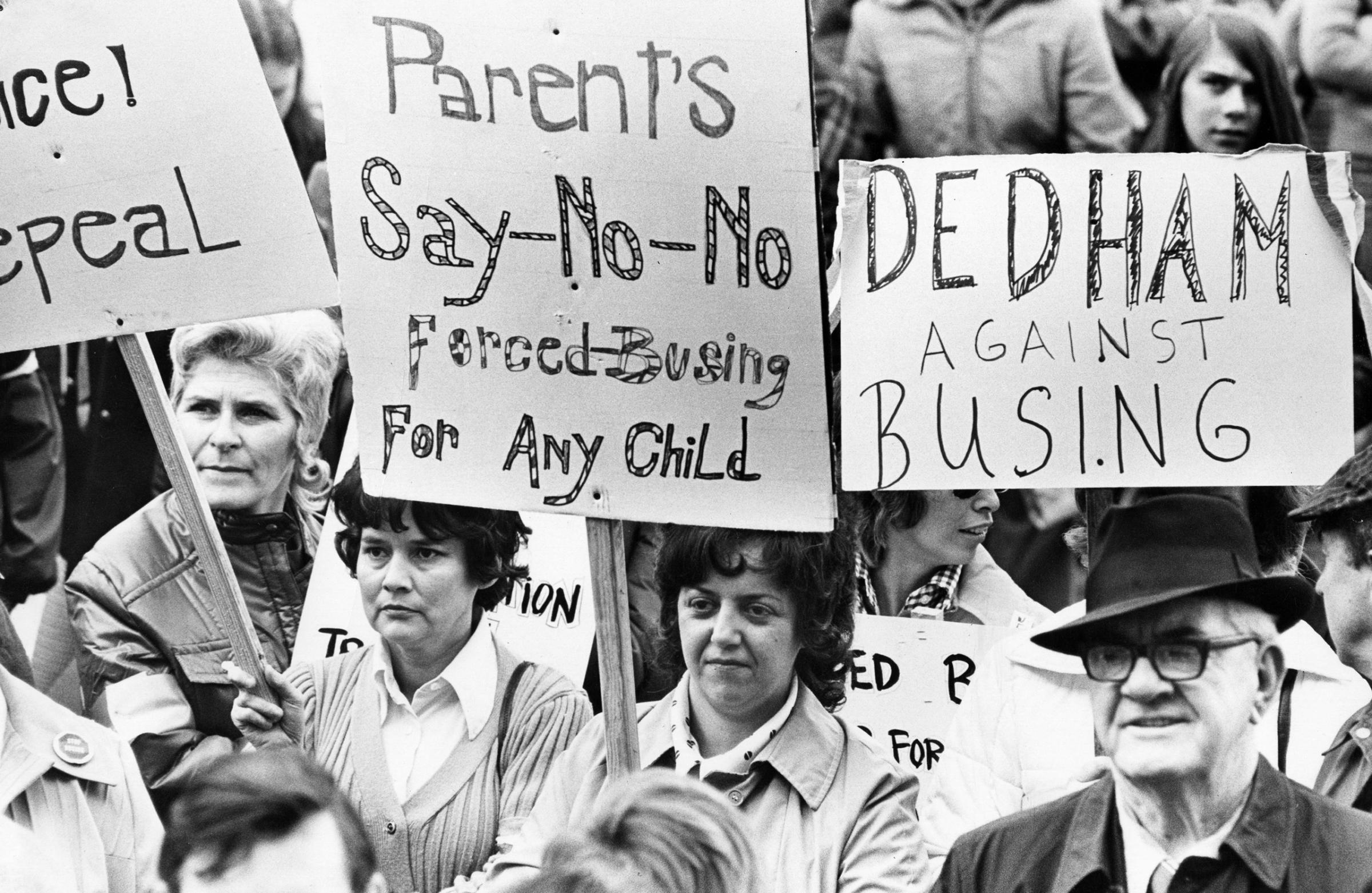

Busing Is Mandated in Boston (June 21, 1974)

Tyler Stovall

In the aftermath of 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, many white liberals and moderates in the North publicly embraced school integration, which they saw as a Southern problem. That idea, however, was quickly disproved. In June of 1974, federal judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled that the Boston School Committee had intentionally segregated the city’s public schools—and that a program of school busing was needed to address the problem.

Much of the city’s white population actively resisted the order, organizing a powerful and sometimes violent anti-busing movement, which helped galvanize nationwide opposition to busing for integration. In 1975 the U.S. Senate, led by both liberals like Joseph Biden and conservatives like Jesse Helms, passed a series of anti-busing measures. The Boston movement showed that many Northern whites were less than willing to promote school integration in their own communities, illustrating the limits of the nation’s commitment to racial justice. Before 1974, American public schools had been gradually moving towards racial integration. In the aftermath of the struggle against busing, the nation’s schools began to resegregate. In some respects, today’s American public schools are more segregated than ever.

Tyler Stovall is humanities dean at UC Santa Cruz and president-elect of the American Historical Association.

Read more about busing, here in the TIME Vault

Deng Xiaoping Comes to Power (July 22, 1977)

T.J. Stiles

One of the most consequential moments in American history occurred somewhere far away: in China on July 22, 1977, when Deng Xiaoping began his rise to power. He brought the world’s most populous nation into the international economy, with countless repercussions. His decisions contributed to an enormous loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States, but also helped to kill inflation. And it didn’t stop there. For example, the cheap manufacture of smart phones and tablet computers has made them nearly ubiquitous, giving rise to the app economy—remaking everything from the taxi business to media. But China’s coal-powered industrialization also has greatly accelerated global warming. China’s shift from an ideological to an authoritarian state helped to end the Cold War, but its nationalism, wealth and assertiveness have challenged the United States on a global scale, from control of Africa’s natural resources to territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

T.J. Stiles is the author of Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, the winner of the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in History.

Read more about Deng Xiaoping, here in the TIME Vault

Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez Is Decided (May 15, 1978)

Arica L. Coleman

Under the law of the Santa Clara Pueblo, the children of Indian men fathered with non-tribal women could be enrolled in the tribe, while enrollment of the children of Indian women fathered by non-tribal men was denied. Julia Martinez, a Santa Clara Pueblo woman married to a Navajo man, charged under the 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act that the law violated her civil rights and her daughter’s. The case set the rights of an individual against the sovereignty of tribal governments—and Supreme Court court, in a decision written by civil-rights icon Justice Thurgood Marshall, decided in favor of the latter. The effect of the decision was immediate. Cases involving violations of the Indian Civil Rights Act declined sharply, and the decision was used as justification for the wholesale disenrollment of large groups of people, such as the Cherokee Freedmen, descendants of former slaves of the Cherokee nation, from the tribes to which they had belonged. As American Indian lawyer Ramon Roubideaux put it, “Martinez set Indian law back 30 years.”

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of race and identity in Virginia, a Choice Outstanding Academic Title for 2014, and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

Read more about the Indian Civil Rights Act, here in the TIME Vault

Jimmy Carter Signs the Refugee Act of 1980 (March 17, 1980)

Erika Lee

The U.S. has a long history as a place of refuge to those seeking freedom from persecution—but until 1980 there was no uniform refugee admissions policy. Refugees were typically allowed into the U.S. on an ad hoc basis with special legislation, like the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which allowed 400,000 displaced Europeans into the country. During the Cold War, other policies typically favored the admission of people fleeing Communist regimes over others.

The 1980 Refugee Act changed all of that. Prompted by the humanitarian crisis in Southeast Asia after the end of the Vietnam War, the act created a permanent and uniform system for admitting and resettling refugees into the U.S. It set an annual cap of refugee admissions and incorporated the United Nations definition of “refugee” into U.S. law, allowing the country to admit people any person with “a well-founded fear of persecution.” Today, the world is home to an estimated 19.5 million refugees—giving special resonance to the 1980 act and the U.S.’s commitment to welcoming refugees.

Erika Lee is Rudolph J. Vecoli Chair in Immigration History at the University of Minnesota. Her book The Making of Asian America: A History was named one of the “Can’t-Miss History Books of 2015” by History Buffs.

Read more about the Refugee Act, here in the TIME Vault

The Betty Ford Center Opens (Oct. 4, 1982)

Kate Andersen Brower

Today, with the opioid crisis currently raging, the importance of the opening of the Betty Ford Center—and Betty Ford’s own painful coming to terms with her own addiction, which she did very publicly—is clear. She brought addiction out of the shadows in a way that no one had done before. Unfortunately, there’s still a huge amount of shame attached to addiction of any sort, but I can only imagine how it would be without the Betty Ford Center, which has helped so many people. Betty said that she had always pictured an alcoholic as a sloppy, disheveled person, not a put-together woman who was living in the White House. Today, we know that addiction is common and doesn’t only happen to a certain type of person. She used her position as former First Lady in a surprisingly personal way that we don’t really see anymore, and she changed the way the country dealt with a very serious condition. Betty Ford saved an untold number of lives by exposing her own private struggle.

Kate Andersen Brower is the author of First Women: The Grace and Power of America’s Modern First Ladies and The Residence: Inside the Private World of the White House.

Read more about changing attitudes toward addiction, here in the TIME Vault

Chicago Meets Oprah Winfrey (Jan 2., 1984)

Juliet E.K. Walker

In 1984, Oprah arrived in Chicago with a parade down State Street, organized by the TV station that ran AM Chicago to introduce her to the city. At the time, for an African American—and a woman at that—to be a co-host of a talk show was just amazing. That moment, and the success that followed, would ultimately change the course of black business history. By 1985, the show was renamed The Oprah Winfrey Show and eventually she would become the first African American woman billionaire. (Her first Forbes billionaire listing came in 2003, nearly a century after John D. Rockefeller became the first American billionaire.) African Americans have been involved in the nation’s economy since 1619, when the first Africans were brought to Colonial America, and black economic equality in is yet to be achieved. Oprah’s visibility and wealth, however, has helped to open a door.

Juliet E.K. Walker, professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, is author of The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship and the 2015 recipient of the Business History Conference’s Lifetime Achievement Award. She is also a recipient of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History’s Carter G. Woodson Scholar’s Medallion.

Sagon Penn Is Acquitted (July 17, 1987)

Vincent Brown

Sagon Penn’s story doesn’t fit conventional narratives. It’s almost never the case that a young black man could be exonerated for killing a policeman. But that’s what happened in 1986 and 1987: juries in two separate trials ultimately decided that Penn, who admitted to the shooting but pled self-defense, was not guilty of murder or manslaughter when he opened fire in the midst of a beating by a San Diego police officer. This was four years before the Rodney King beating in Los Angeles. I saw that event as a reaction by the police to an erosion of what they saw as their prerogative of impunity. A police force maintains its authority by embodying the law, and officers of the law are due special protections. But police have, at times, abused this privilege, placed themselves above the law and used their badges to shield unlawful behavior. It is perhaps no coincidence that, not long after Penn’s juries acknowledged that behavior, police made an example of Rodney King. Meanwhile, Penn was never able to get his life back on track and ended up committing suicide in 2002.

Vincent Brown is Charles Warren Professor of History and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard, and director of the History Design Studio.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com